Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Dr David Hille, Public Health Registrar, Department of Health, Perth, Western Australia, Australia. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. November 2020.

Introduction Demographics Causes Clinical features Complications Diagnosis Treatment Public health interventions

Dracunculiasis, also known as 'Guinea worm disease', is a parasitic infestation by the nematode ('roundworm') Dracunculus medinensis. It is an ancient disease documented back through millennia and is now close to eradication worldwide.

Following eradication from many countries, dracunculiasis is now localised to rural communities in parts of sub-Saharan Africa with inadequate access to clean drinking water. Eradication initiatives have seen the annual incidence of dracunculiasis decline substantially since the 1980s. The disease was once endemic in twenty countries, with more than three million cases estimated in 1986. In 2019, cases of dracunculiasis were reported in only four countries: Angola, Chad, Cameroon, and South Sudan.

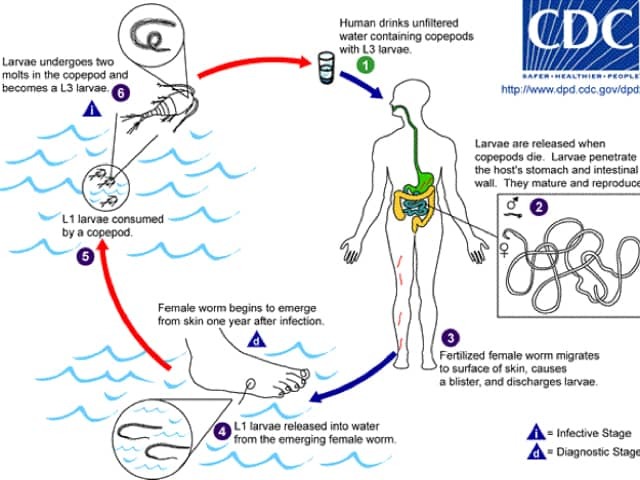

Dracunculiasis is caused by Dracunculus medinensis, a tissue parasite. Dracunculus medinensis larvae are ingested by tiny crustaceans (copepods or “water fleas”) present in a water source. People become infected after drinking contaminated water, or eating raw or incompletely cooked fish from contaminated water sources. Gastric juices kill the crustaceans, releasing the Dracunculus medinensis larvae into the small bowel.

Dracunculus medinensis larvae migrate through the bowel wall into the connective tissue, where the larvae mature and mate 2–3 months later. The male worm dies soon after mating. Pregnant adult females, which can grow to one metre in length (but only 1–2mm thick), slowly migrate to the skin surface as they mature over 12 months. The lower limb is the most common site they migrate to in about 90% of all cases.

When the skin ulcer makes contact with a fresh water source, the female worm extends from the wound to release larvae into the water. The transmission cycle then recommences.

Although it was thought there was no animal reservoir, the worms and larvae have recently been identified in dogs, with a possible cycle through them back into water sources.

Life cycle of Dracunculus medinensis

When the mature female Dracunculus medinensis approaches the skin surface, a papule forms usually on the foot or lower leg below the knee. A burning pain precedes the appearance of the papule. This papule develops into a blister, which enlarges over several days before rupturing to expose the parasite. Redness, itch, swelling, and induration can occur around the blister. Often multiple worms are emerging through the skin at the same time.

Systemic symptoms including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, dizziness, and fever can coincide with blister development, and settle when the blister bursts. There may be an associated very itchy urticarial rash.

Dracunculus medinensis female worm emerging from the skin

Severe physical limitation of the affected limb can occur during the acute phase, lasting up to twelve weeks. A subset of patients may experience ongoing pain on mobilisation of the affected limb more than one year after removal of the parasite. Temporary or permanent disability exacerbates the pre-existing economic disadvantage affecting communities at risk of dracunculiasis.

Ulcers can become secondarily infected with bacteria, leading to cellulitis, abscesses, septic joints, and systemic sepsis, which can be rarely fatal. Tetanus may also complicate dracunculiasis.

Sometimes the worm migrates to an internal organ or surface, resulting in inflammation, compressive symptoms, or abscesses.

Lasting immunity does not develop to dracunculiasis and it is common for an individual to be infected multiple times over a lifetime in endemic areas.

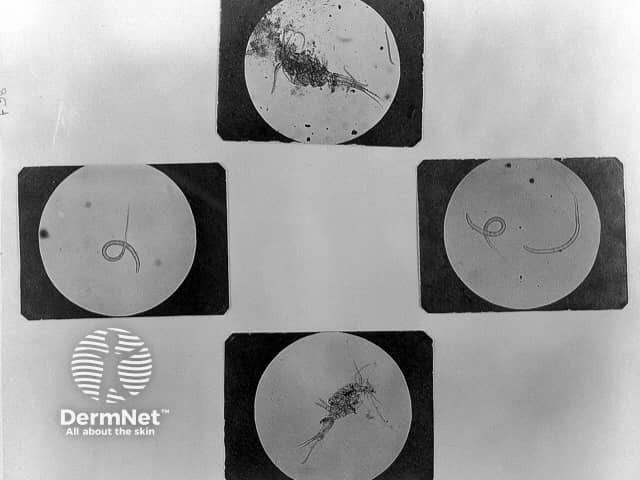

Formal diagnosis can be made by parasitological examination of a worm that has been removed from the patient.

There is no specific treatment for dracunculiasis. The mature Dracunculus medinensis worm is removed by gentle traction as it emerges from the skin ulcer. This process can take several weeks. As the parasite is long and thin, it can be wrapped around a stick ('spinning') to facilitate tension during the removal, extracting a few centimetres of worm each day taking care not to break it. Surgical removal has been advocated more recently as it is quicker, limits complications, and prevents spread.

Cleaning and dressing the wound reduces the risk of secondary bacterial infection. Covering and wrapping the wound minimises release of larvae. Topical or systemic antibiotics can be used to treat or prevent secondary bacterial infections.

Public health interventions are key to eradicating dracunculiasis from affected communities.

There is no vaccine for dracunculiasis.