Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Created 2009.

There have been various published classifications of vasculitis relating to aetiology, clinical presentation or the size of affected blood vessels. Vasculitis may affect capillaries, small vessels or larger arteries. It often results in palpable purpura, which are red, purple or black haemorrhagic macules, papules and plaques, but other morphologies may occur such as urticated plaques, nodules and ulcers.

Capillaritis, also known as pigmented purpura, results in tiny red dots, described as cayenne pepper spots or larger reddish-brown patches that persist for weeks to months. The cause of capillaritis is usually unknown. Occasionally it arises as a reaction to a medication, a food additive or a viral infection. It may develop on the lower legs after exercise.

Capillaritis Capillaritis Capillaritis Capillaritis

There are several descriptive terms for capillaritis.

There is no known cure for most cases of capillaritis. Topical steroids can be helpful for itching but rarely clear the eruption. If the lower leg is affected, graduated compression elastic hose may be helpful.

Hypersensitivity vasculitis results in palpable purpura with or without systemic involvement (kidney, muscles, joints, GI tract, peripheral nerves). It is thought to be due to the deposition of circulating immune complexes, and is associated with the release of vasoactive amines and complement activation.

The antigen is not always identified but may include:

Onset may be acute, subacute or chronic, depending on aetiology. The skin lesions may be asymptomatic, or sore and itchy. Purpuric lesions may be scattered, clustered or confluent and are predominantly on the lower leg although thighs and buttocks are often also affected. They may blister, erode or ulcerate. The lesions persist for several weeks, and may recur (depending on underlying cause).

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a subset of hypersensitivity vasculitis associated with IgA. It is more common in children and may follow group A streptococcal infection. Characteristically, palpable purpura is associated with abdominal pain, bloody diarrhoea, haematuria and arthritis. It can result in progressive renal failure.

Mild post-streptococcal vasculitis Severe post-streptococcal vasculitis Henoch-Schönlein purpura Hypersensitivity vasculitis of unknown cause

Investigations of hypersensitivity vasculitis should include:

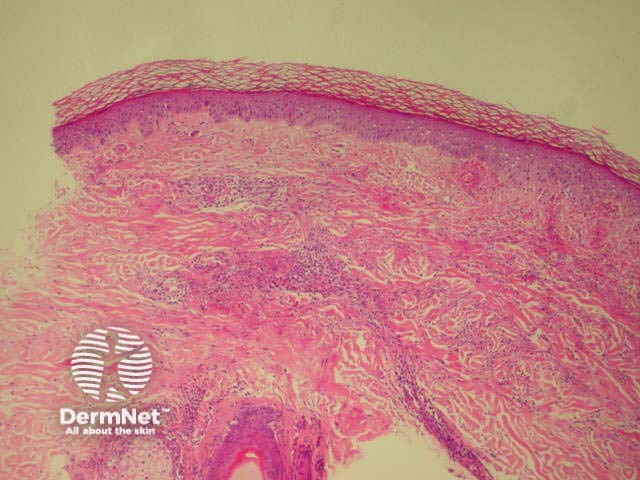

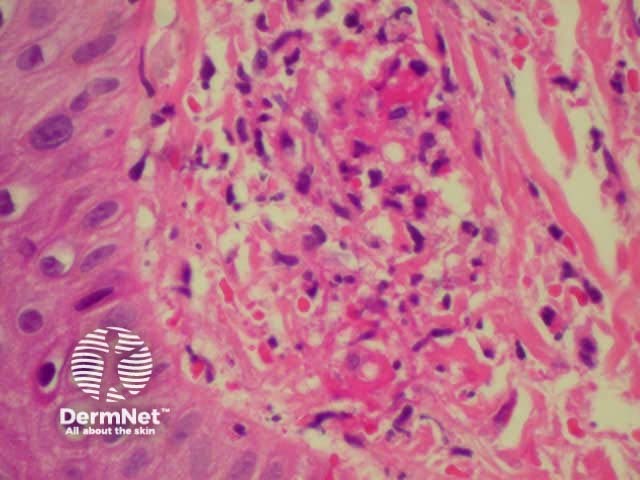

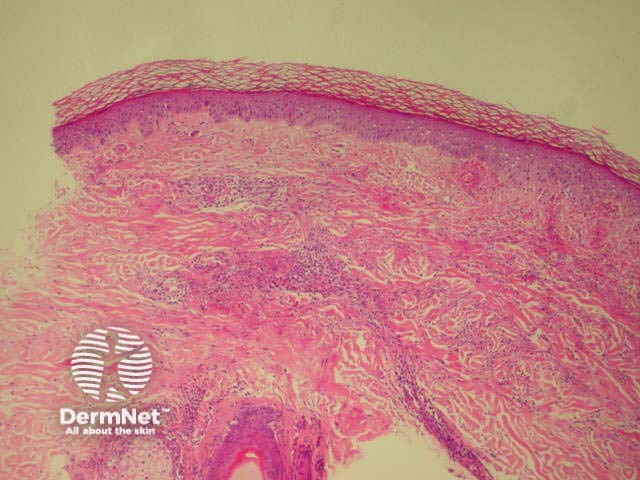

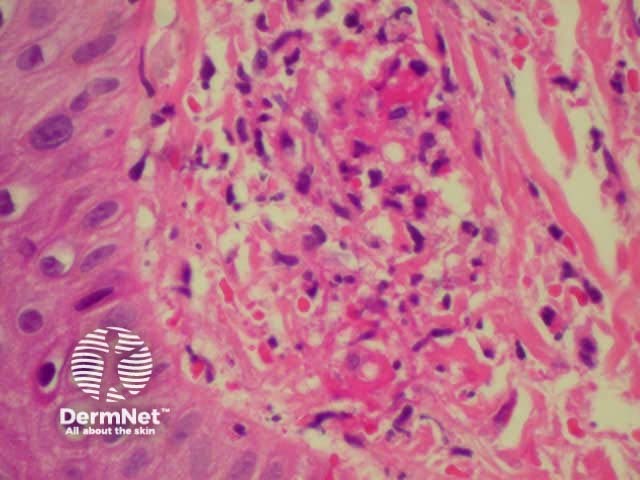

Dermatopathology shows a necrotising vasculitis.

Dermatopathology of hypersensitivity vasculitis Dermatopathology of hypersensitivity vasculitis

Treatment should include management of the underlying disease, if known. In severe cases it may be necessary to treat with oral prednisone or immunosuppressive agents including azathioprine and azathioprine. Mild cases may respond to a variety of anti-inflammatory agents such as dapsone.

Polyarteritis nodosa is a necrotising vasculitis affecting small and medium sized muscular arteries. It is very rare in children. It may be confined to the skin, but more often also affects renal and visceral arteries and peripheral nerves. It is a chronic disease and can result in considerable morbidity.

Polyarteritis nodosa may be associated with hepatitis B infection and less frequently with other infections including beta haemolytic streptococcus.

Cutaneous signs include red or violaceous subcutaneous vascular nodules, livedo reticularis and chronic leg ulcers.

Early vascular nodule Livedo pattern on feet Severe ulceration

Systemic disease results in hypertension, cerebrovascular accident, mononeuritis multiplex, myalgias, renal failure, visual disturbance and other problems.

Dermatopathology shows neutrophilic infiltrate throughout muscular vessel wall, fibrinoid necrosis, thrombosis, infarction and haemorrhage.

Characteristically p-ANCA is positive (antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies).

Management may include systemic steroids, cyclophosphamide and other immune suppressive agents.

Urticarial vasculitis is characterised by recurrent episodes of skin lesions that look like urticaria, i.e. erythematous oedematous plaques, but the lesions persist for several days and are often followed by macular purpura or bruising. It is rare in children. Dermatopathology shows leukocytoclastic vasculitis and it is thought to be another manifestation of immune complex deposition.

Urticarial vasculitis Urticarial vasculitis

Urticarial vasculitis is often associated with fever, arthralgia and elevated ESR. About half are associated with hypocomplementaemia and systemic lupus erythematosus. Infection or drugs provoke some cases.

Other forms of vasculitis with cutaneous signs include:

Investigations of hypersensitivity vasculitis should include:

Dermatopathology shows a necrotising vasculitis.

Dermatopathology of hypersensitivity vasculitis Dermatopathology of hypersensitivity vasculitis

The dermatopathology of PAN shows neutrophilic infiltrate throughout muscular vessel wall, fibrinoid necrosis, thrombosis, infarction and haemorrhage. Characteristically p-ANCA is positive (antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies).

Dermatopathology of urticarial vasculitis is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Treatment of hypersensitivity vasculitis should include management of the underlying disease, if known. In severe cases it may be necessary to treat with oral prednisone or immunosuppressive agents including azathioprine and azathioprine. Mild cases may respond to a variety of anti-inflammatory agents such as dapsone. Management of PAN may include systemic steroids, cyclophosphamide and other immune suppressive agents.

Describe how vasculitis may be distinguished from child abuse.

Information for patients

See the DermNet bookstore