Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Created 2009.

Describe clinical features, investigations, their complications and management:

Chronic ulceration frequently affects the legs, in association with chronic venous insufficiency (45-80%), chronic arterial insufficiency (5-20%), diabetes (15-25%) and or peripheral neuropathy. About 1% of the middle-aged and elderly population is affected by leg ulceration. Ulcers are often precipitated by minor injury.

Take a complete medical history and perform a thorough general examination in patients presenting with chronic leg ulcers. If necessary, investigate by blood tests, vascular blood flow studies and biopsy.

Even when the cause is known, it may be difficult or impossible to correct the underlying defect resulting in persistent or recurrent ulceration. Frequently there are several factors, particularly in diabetics who may have venous, arterial, neuropathic and infective causes.

Chronic venous insufficiency arises from calf muscle pump dysfunction. It is associated with:

High venous pressure results in increased capillary permeability allowing large fibrin molecules to be deposited around the capillaries, which acts as a barrier to diffusion of oxygen and nutrients resulting in ischaemia and necrosis.

Venous insufficiency results in aching, swollen lower legs that feel more comfortable when elevated. Signs include:

Pigmentation due to venous insufficiency Typical stasis dermatitis Severe lipodermatosclerosis Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV-patient3)

Prior to ulceration there may be a blue-red patch or atrophie blanche (scarring with prominent tortuous capillaries). A minor injury causes a punched-out ulcer that expands with an irregular brownish border. It may be painless or painful, dry or oozy. The most common site is the medial lower aspect of the calf especially over the malleolus.

Typical venous ulceration

Typical venous ulceration

Atrophie blanche with early ulceration

Close-up of atrophie blanche

Complications of chronic venous ulceration include:

Skin infection has caused

Irritant dermatitis from

Dermatitis due to

Investigations to delineate superficial and deep incompetent veins include phlebography and Duplex sonography.

Management should include:

Arterial insufficiency is most often due to atherosclerosis. Ischaemia and infarction may also be due to vasculitis, chilblains, Raynaud's phenomenon, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), cryoglobulinaemia, hyperviscosity syndrome, septic embolisation, aneurysms, drug-induced necrosis (warfarin, heparin, ergot, intra-arterial injection), connective tissue disease, external compression or entrapment.

Atherosclerosis results in leg ulceration because of acute or chronic ischaemia and/or atheroembolisation of fibrin, platelet and cholesterol debris from a distal source into small vessels of the skin.

Risk factors include:

Lower extremity arterial insufficiency results in pain on exercise (intermittent claudication) and eventually pain at rest, most marked at night. Sudden onset of localised pain and tenderness may indicate embolus, especially if arising postoperatively.

Signs of arterial insufficiency include:

Arterial ulcers are painful and most often arise over bony prominences such as between the toes or on the heels, following minor trauma. A well-demarcated purple patch progresses to blackened slough or dry gangrene. The slough sheds to reveal a punched out ulcer with a sharp border. It may be very deep exposing tendons.

Athlete's foot predisposes

Arterial ulcer

Painful ulcers on the anterior shin may be caused by uncontrolled hypertension in the absence of occlusion of larger arteries.

Poor tissue perfusion predisposes to infection particularly if there are breaks or fissures such as with athlete's foot (interdigital maceration) or ulceration.

Investigation should include Doppler studies and arteriography. The Ankle Brachial Pressure Index (ABPI) is derived by dividing the Doppler measurement of ankle systolic pressure by the brachial systolic pressure. In the absence of arterial disease the ABPI is below 1. An index of less than 0.8 indicates significant arterial disease.

Management should include:

In New Zealand these usually relate to underlying diabetes mellitus so there is also arteriolar ischaemia.

Symptoms of sensory neuropathy include pain, paraesthesia and anaesthesia. Signs include:

In response to pressure, the skin of the sole, toe or heel increases in thickness (callus) but with a minor injury breaks down and ulcerates. The most common sites are the soles, metatarsal head, great toe (bunion) or heel. These ulcers are frequently secondarily infected.

Paraplegia

Spina bifida

Diabetes

Diabetes

Management must include careful attention to removing weight from pressure points (if necessary with plaster cast) and debridement of callus around the ulcer margin.

Skin cancers may arise on the lower legs especially in women who have been habitually sun-exposed. However, chronic ulceration from other causes may also predispose to malignancy, so a biopsy of the ulcer margin is indicated if there is doubt about the diagnosis or in cases where there is failure to heal.

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

The healing edge of an ulcer may also resemble a malignancy clinically and histologically (pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia).

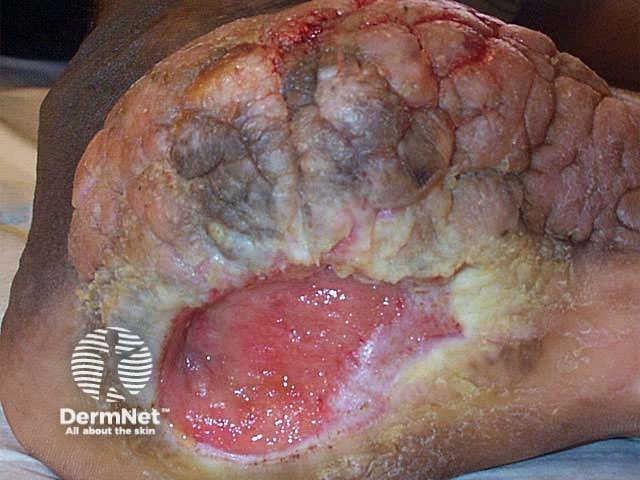

Pressure (decubitus) ulcers most often occur over the sacrum (60%), ischial tuberosities and greater trochanter but may also arise on the heel, knee and ankle. They are most often seen in elderly chronically bedridden patients or following injury to the spinal cord. Ischaemic damage and necrosis arises because the dermis and subcutaneous tissue have been compressed for a prolonged period.

Predisposing factors include:

Pressure ulcers are categorised as follows:

Early: blanching erythema

Stage 1: non-blanching erythema

Stage 2: bullae, necrosis of superficial dermis, shallow ulceration

Stage 3: deep necrosis, full-thickness ulceration

Stage 4: extensive necrosis affecting muscle, bone with undermined border.

Typically the diameter of the surface of the ulcer is less than its base. If sensation is intact, pressure ulcers are very painful.

Chronic pressure ulcer

Management must include repositioning the patient every hour or two, inspection of the skin for breakdown over pressure points. Prophylaxis should include:

Ulcer management should include debridement, wound dressings, flaps and skin grafts and management of infectious complications.

Chronic leg ulceration is less commonly due to the following conditions:

These conditions will not be specifically discussed in this module.

Cellulitis

Necrotising fasciitis

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Polyarteritis nodosa

Necrobiosis lipoidica

Debridement

Removal of fibrin clot and the corrupt matrix stimulates the accumulation of a competent provisional matrix. A basic principle of treatment is the removal of sloughy, necrotic and devitalized tissue to prevent wound infection and delayed healing. Debridement converts the chronic wound into an acute wound so that it can then progress through the normal stages of healing.

Compression therapy

Bed rest short term reduces oedema but is impractical and hazardous long term. The current standard of care for venous ulceration and chronic lymphoedema includes compression therapy, which prevents the increase of venous pressure that arises with dependency and exercise. Compression is contraindicated if there is arterial insufficiency i.e. ABPI less than 0.8 and with caution in diabetes because of microangiopathy.

There are several options including 4-layer bandaging, elastic graduated compression hosiery and an Unna boot (gauze bandage impregnated with zinc oxide).

Medical hosiery is available in three different classes with increasing ankle pressure.

Stockings are difficult to apply over active ulcers and dressings. Elasticated bandages can be applied with constant tension to provide graduated compression with the highest pressure at the ankle. Padding should be applied in strips over bony prominences to prevent excessive pressure.

Bandages are available with different predetermined levels of compression; light, moderate, high and extra-high performance. The latter are reserved for very large and oedematous limbs. They are usually applied in the form of a spiral with 50% overlap between turns i.e. producing a double layer. A figure-of-8 pattern results in higher pressure. The fatter the leg, the lower the pressure.

Some products have a geometrical design printed at intervals along them. The object is to stretch the bandage aiming to convert a rectangle into a square to produce a sustained and constant level of tension over 40mm Hg.

Four-layer bandaging (e.g. Profore™) refers to:

Profore bandage

Unna boot

Sigvaris compression stockings

Occlusion

Occlusion aids wound healing by providing a moist environment. Hydrocolloids have proved particularly useful.

Treat infection

Prevent contamination and identify significant local or systemic infection. Treat this with appropriate systemic antibiotics. Topical antibiotics are best avoided because their use results in increased resistance and contact sensitisation.

Accelerate wound healing

Ensure the patient metabolic and nutritional status is adequate. Consider supplementary protein, iron, vitamin-c and zinc if these are deficient.

New products to aid wound healing require further research. They include:

For those wounds that require more than closure by secondary intention, plastic surgical techniques including pinch grafts and split skin grafts can then be used to provide a functional and effective wound closure.

Vacuum assisted closure device

Discuss the pros and cons of hospital admission in the management of chronic leg ulceration.

Page 5 of 6. Next topic: Wound dressings. Back to: Wound healing contents.

Acknowledgement: some images on these pages have been copied from product-related websites.

Information for patients