Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Assoc Prof Patrick Emanuel, Dermatopathologist, Auckland, New Zealand; Dr Harriet Cheng, Dermatology Registrar, Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand, 2013.

Introduction

Histology

Three stages of eczema

Types of eczema

Differential diagnoses

Special studies

Eczema is a common skin condition with multiple clinical patterns, characterised histologically by a spongiotic tissue reaction pattern. The terms eczema and dermatitis are often used interchangeably to denote a polymorphic inflammatory reaction pattern involving the epidermis and dermis. However, 'dermatitis' means inflammation of the skin and is not synonymous with eczematous processes. The consensus among most dermatopathologists is that the expression 'eczema' should be replaced with the term 'spongiotic dermatitis' to reflect the histopathologic changes that underlie the so-called 'eczemas'.

The spongiotic tissue reaction pattern is characterised by intercellular oedema within the epidermis (spongiosis). Initially, there is a widening of intercellular spaces between keratinocytes and elongation of the intercellular bridges. Further accumulation of fluid leads to the formation of intraepidermal vesicles. Spongiotic dermatitis is a dynamic pathological process; vesicles come and go and can be situated at different levels of the epidermis. Infiltration of the epidermis with lymphocytes (exocytosis) is common. Parakeratosis forms above areas of spongiosis, probably as a result of an acceleration in the movement of keratinocytes towards the surface. Droplets of plasma accumulate in the mounds of parakeratosis. Dermal changes include varying degrees of oedema and a superficial perivascular infiltrate with lymphocytes, histiocytes and occasional neutrophils and eosinophils.

Clinically, eczema is grouped according to aetiology. Histologically, it is more useful to classify eczema based on chronicity. Histologically, there are three stages of eczema: acute, subacute, and chronic. An eczematous disease may start at any stage and evolve into another.

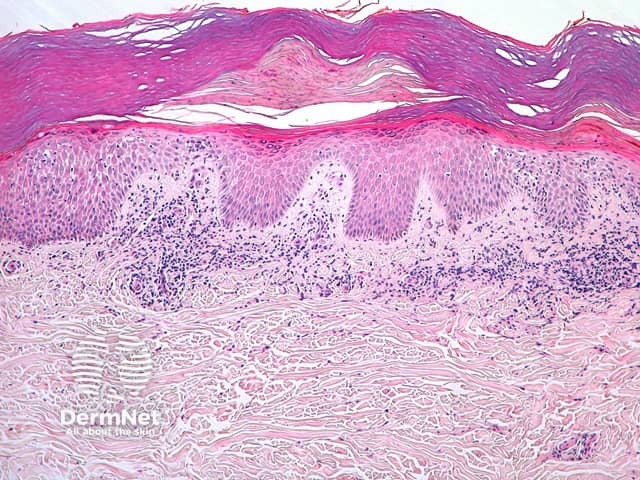

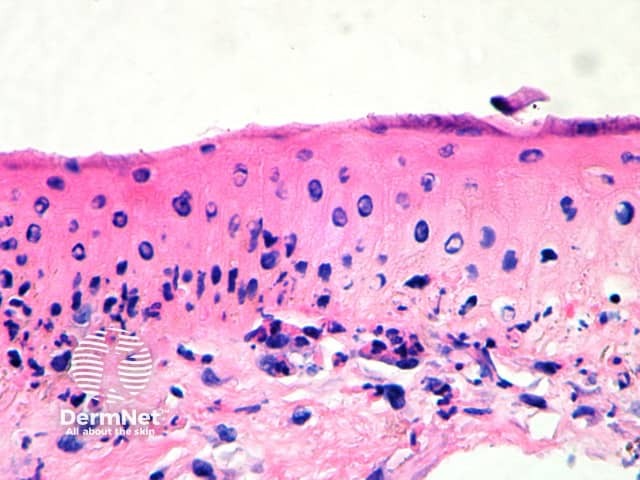

Acute spongiosis is typified by massive intercellular oedema of the epidermis with a widening of the intercellular spaces, disruption of desmosomes and formation of microvesicles. Although vesicles are usually intraepidermal, with sufficient vesiculation, they can become subepidermal. Vesicles are filled with proteinaceous fluid containing lymphocytes and histiocytes (figure 1, arrow). In allergic/contact dermatitis, eosinophils may be prominent (eosinophilic spongiosis).

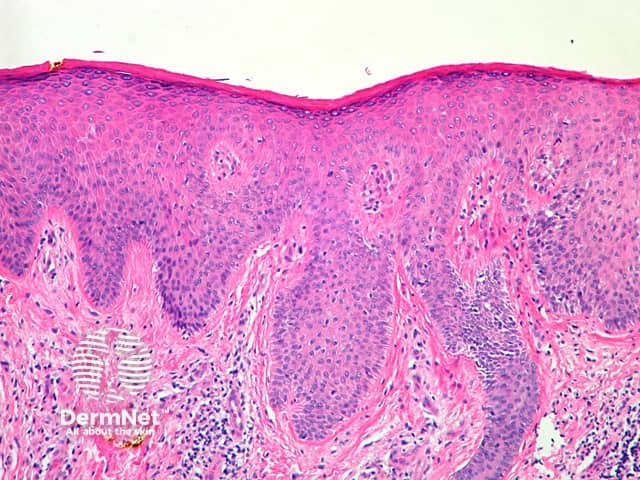

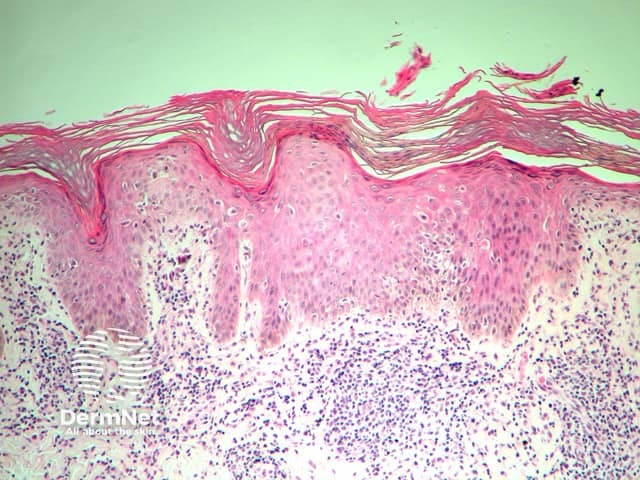

This is the most frequently encountered type of spongiotic dermatitis. The degree of spongiosis and exocytosis of inflammatory cells is mild to moderate. Irregular acanthosis and parakeratosis are additional features compared with acute spongiotic dermatitis. A superficial dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate, swelling of endothelial cells, and papillary dermal oedema are present (figure 2).

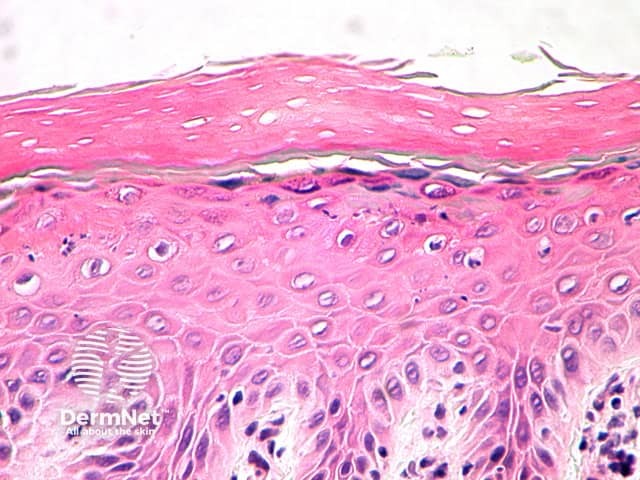

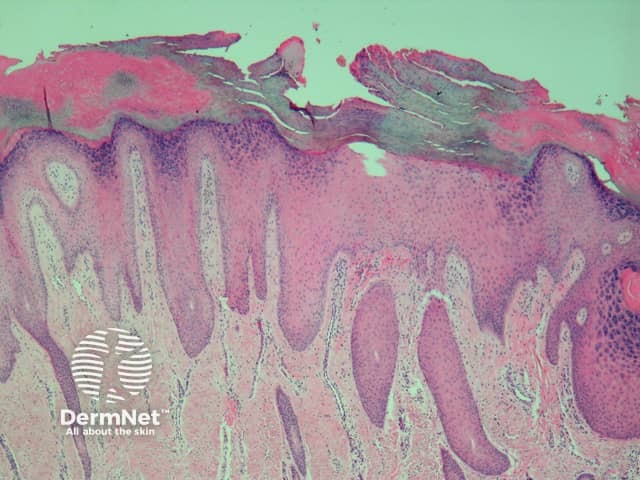

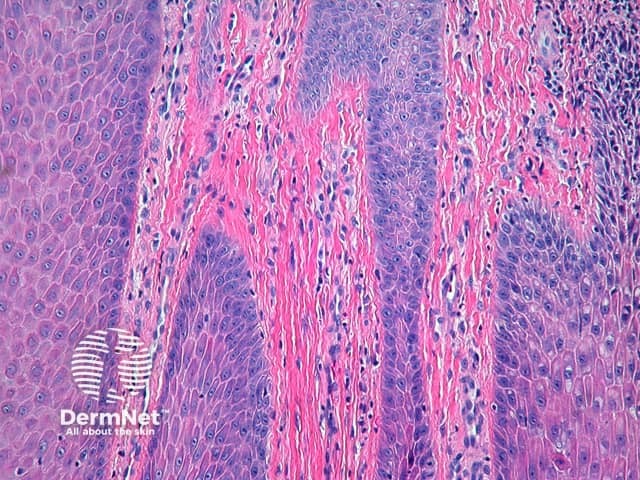

In chronic spongiotic dermatitis, the degree of spongiosis is often mild and difficult to appreciate. Vesiculation is uncommon. There is significant epidermal acanthosis, which may show a psoriasiform pattern with hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis and minimal parakeratosis. Fibrosis of the papillary dermis may be present (figure 3).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

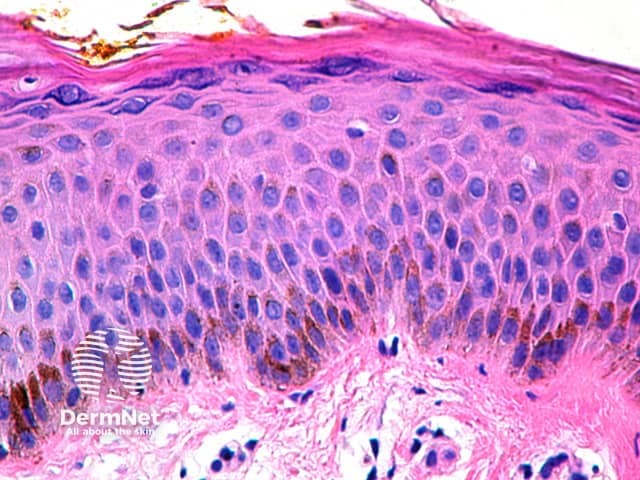

Atopic dermatitis is a common skin condition, particularly in children and is associated with personal and family history of atopy. Although acute and subacute spongiotic patterns have been described in atopic dermatitis, these are far less common than chronic spongiosis. Interestingly, a follicular pattern is not uncommon which shows spongiosis of the infundibular portion of follicles and a sparse dermal infiltrate (figure 4, arrow shows follicular spongiosis). The follicular pattern is found with increased frequency in more deeply pigmented cutaneous phototypes.

Irritant contact dermatitis is provoked by contact with water, detergents and other chemicals and subsequently occurs most commonly on the hands, The histology of irritant contact dermatitis is typically mild spongiosis, epidermal cell necrosis, and neutrophilic infiltration of the epidermis. Figure 5 shows an early lesion with infiltration of the epidermis by neutrophils. Figure 6 shows a more acute and severe example with full-thickness necrosis.

Allergic contact dermatitis occurs when there is sensitisation to a usually tolerated environmental contact such as nickel, fragrance, hair dye or preservatives. A pattern of subacute, chronic dermatitis or acute dermatitis may be seen. The dermal inflammatory infiltrate predominately contains lymphocytes and other mononuclear cells (figure 7). Allergic contact dermatitis occasionally provokes atypical T-cell infiltrates which may simulate mycosis fungoides.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Discoid eczema or nummular dermatitis is a particularly chronic eczema characterised clinically by papules or papulovesicles which coalesce into coin-shaped patches. Histological changes vary with chronicity. Early lesions show moderate spongiosis with mild acanthosis and exocytosis of inflammatory cells. With time, the degree of acanthosis increases. Additional features include scale-crust formation above the thickened epidermis, and dermal perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. It is usually prudent to perform special stains to exclude a fungal infection (tinea corporis).

Stasis dermatitis is a common condition affecting the legs secondary to the impaired venous circulation. Spongiosis is usually mild with foci of parakeratosis and scale crust. Ulceration is a common complication. Dermal changes are prominent with neovascularisation, haemosiderin deposition and varying degrees of fibrosis (depending on chronicity).

Seborrhoeic dermatitis most commonly occurs on the scalp and face secondary to toxic substances produced by yeasts. Histologically there is spongiosis which may be acute, subacute or chronic depending on the lesion biopsied. The spongiosis may have an area of overlying scale crust and is often situated over a hair follicle (figure 8). Presence of neutrophils within the epidermis or stratum corneum should prompt a further examination for yeasts with PAS staining. More chronic lesions show progressive psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with less spongiosis. Dermal changes include mild oedema of the papillary dermis with a mild superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes and neutrophils.

Asteototic eczema develops as the result of very dry skin. It is most common in the elderly and on the lower limbs. Histologically, the most common finding is a mild subacute spongiotic dermatitis. The stratum corneum is compact and slightly irregular (figure 9).

Id reaction or autoeczematisation describes the occurrence of generalised eczema in response to a localised dermatosis or infection at a distant site. Clinically the Id reaction is polymorphous including pompholyx-like reactions affecting hands and feet or more generalised papular eruptions. Histology of the id reaction often mimics that of the initially localised dermatosis or shows a spongiotic reaction pattern with varied intensity. Mild dermal oedema and lymphocytic infiltration are reported.

Lichen simplex is a type of neurodermatitis characterised by areas of skin thickening in response to repeated scratching or rubbing. Histologically, there is marked hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis and occasional small foci of parakeratosis. The epidermal ridges are elongated and irregularly thickened. Mild spongiosis is variably present depending on the cause. Papillary dermal fibrosis is a characteristic feature (figure 10).

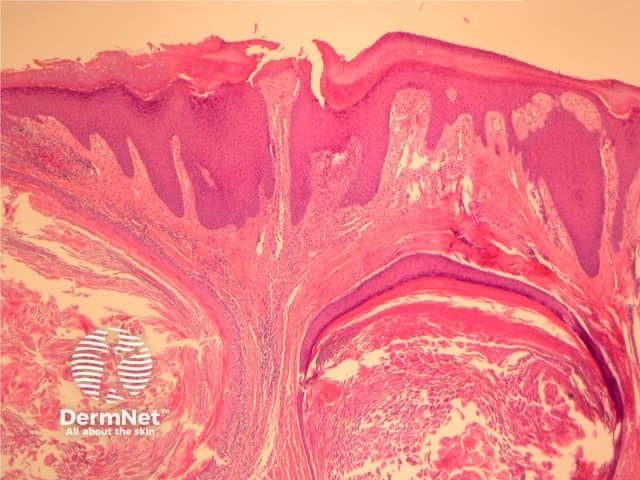

Nodular prurigo is an intensely itchy skin condition of unknown aetiology, characterised by itchy firm lumps. Histologically, there is increased acanthosis compared with lichen simplex, orthohyperkeratosis and hypergranulosis Areas of acanthosis and dilation of follicles form a discrete mass which may be appreciated histologically (figure 11). Mild spongiosis and parakeratosis are occasional features. Lesions are often eroded secondary to excoriation, and there may be marked secondary changes to mimic a squamous carcinoma. Dermal changes include vascular hyperplasia, perivascular inflammatory infiltrate (consisting predominantly of lymphocytes, histiocytes and plasma cells) and fibrosis of the papillary dermis (figure 12).

Acral skin can be easily identified histologically due to the thickness of the stratum corneum and absence of follicular structures. The acute form of vesicular hand dermatitis is characterised by intraepidermal spongiotic vesicles or bullae. The epidermal thickness is normal (figure 13). In chronic hand dermatitis, there is a predominance of parakeratosis and acanthosis with minimal or no spongiosis and a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.

If a skin biopsy is taken in hand dermatitis, special stains for fungal elements should be performed to rule out a dermatophyte infection (tinea).

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

The histopathologic features which characterise spongiosis also occur in a myriad of other dermatoses that are not classically classified as 'eczema', which further confuses the definition. Examples of this include but are not limited to pityriasis rosea, Gianotti Crosti syndrome, the annular erythemas, miliaria, Grover disease, polymorphous light eruptions, papular urticaria, lichen striatus, and some pigmented purpuras. Diagnosis of the particular type of spongiotic dermatitis depends upon precise clinicopathologic correlations. For the pathologist to appropriately evaluate the biopsy, he or she must know the site and distribution of the lesions as well as the age of the patient. The clinical morphology of the lesions is also important: Are they papules, vesicles, bullae, plaques or patches? Are they pruritic? Are excoriations present? How long have the lesions been present? Are they responsive to conventional therapy?

In many instances, the pathologist can only make a diagnosis of the general category 'spongiotic dermatitis, not otherwise specified'. The pathologist should avoid diagnosing an eruption as spongiotic or eczema when the pathologic changes actually represent a spongiotic simulant of eczema. For example, if the lesions are non-pruritic, the pathologist should consider other diagnoses. If capillaritis is present, it may suggest a pigmented purpura, in which case an iron stain should be ordered. A special stain for fungal forms (PAS or Grocott) should be ordered in most cases to exclude a dermatophyte infection. Acrally located eruptions in younger individuals should raise the possibility of Gianotti Crosti syndrome. If the clinical lesions are disseminated, itchy papulovesicles, the biopsy should be step-sectioned to search for such diagnoses as Grover disease (which will display acantholysis) or papular urticaria (which will contain numerous interstitial eosinophils).

More often than not, histopathologic examination does not allow for a more explicit designation of the aetiology or pathogenesis. It is incumbent on the pathologist to attempt to be as specific as possible, and on the referring physician to provide pertinent clinical information.

PAS stain should be performed to rule out a fungal infection.