Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Lesions (cancerous) Diagnosis and testing

Author: Dr Matthew Howard, Clinic/Research Fellow, Victorian Melanoma Service, Melbourne, VIC. Australia. Reviewed by Dr Martin Cherk, Nuclear Medicine Physician and Medical Oncologist, Alfred Health, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. DermNet Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/ Prof. Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. January 2020.

Introduction Importance Radiographic investigations used in staging and surveillance Which patients should undergo radiographic investigations Benefits Controversies and disadvantages How often should scans be performed?

Radiographic investigations produce images of tissues and bones under the skin. The term is often used to include a variety of imaging methods using X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, ultrasound scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

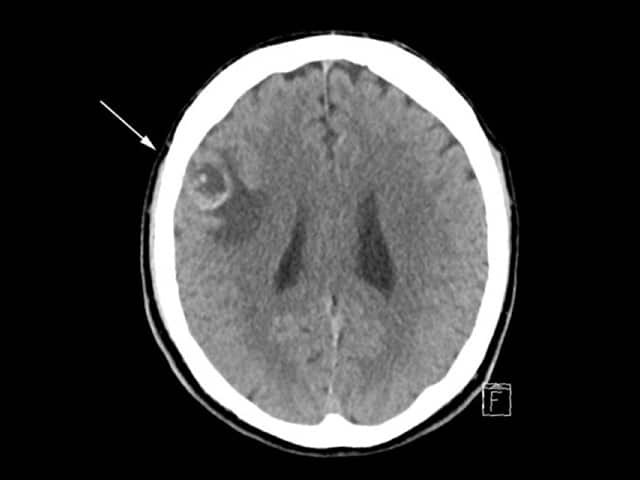

CT scan of brain with melanoma metastasis

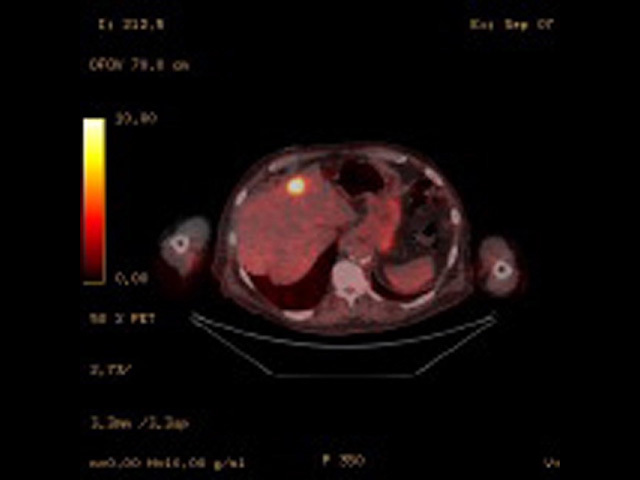

Fused PET/CT image of liver metastasis

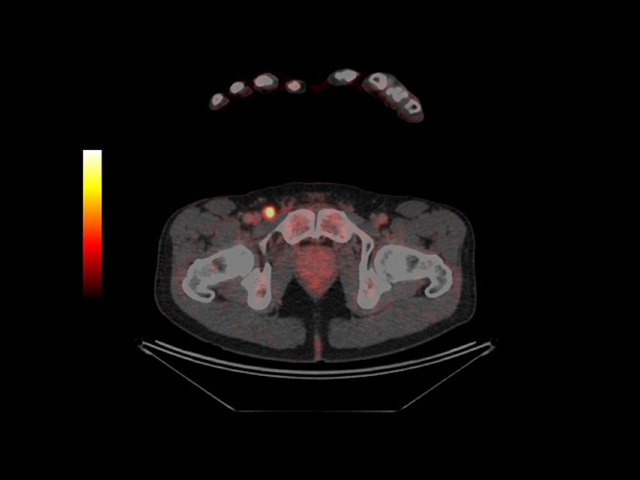

PET-CT scan revealing metastatic melanoma in groin

There are benefits for melanoma patients from radiographic investigations, such as the early detection of metastases or for reassurance, but there are also risks, such as detection of unimportant lesions (false-positives) or missed metastases (false negatives). Follow-up should include evaluation of any symptoms and examination of the site of the original tumour and regional lymph nodes. Regular skin examinations are also important as radiographic investigations rarely detect new primary melanomas.

There are three key indications for radiographic investigations of patients with melanoma.

Guidelines and standards indicate that investigations are not indicated for melanoma in situ (Stage 0) or thin invasive melanoma (Stage I or II) with no clinical symptoms or signs of metastasis. The appropriate patients for staging or surveillance are those at significant risk for distant metastases [4].

Although primary melanoma tumours and local metastases in the lymph nodes or in-transit can often be detected on clinical examination, clinical monitoring for deep lymph nodes and distant viscera is more difficult. Distant visceral metastatic disease is often asymptomatic until advanced, when it may be difficult to remove surgically [1].

Basic radiological investigations such as chest x-ray (CXR) can detect occult metastatic melanoma, but their two-dimensional soft-tissue views are limited [5]. Thus many patients will be referred for CT, positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT), ultrasound imaging, and MRI scans.

CT and PET-CT scans are commonly used in staging and surveillance of many solid malignancies.

Ultrasound imaging is used to monitor regional lymph node basins for metastases. The accuracy of ultrasound is dependent upon the skill and experience of the sonographer [7,8].

MRI provides high-resolution imaging.

Radiographic investigations are appropriate for patients with stage III metastatic melanoma, where there has been histologically confirmed spread of melanoma to lymph nodes, in-transit metastases, or satellite metastases. These patients are at high risk of recurrence or progression to stage IV metastatic melanoma [10–12]. The relative poor mortality of stage IIC melanoma also merits consideration of surveillance [12].

Ultrasound surveillance of the regional nodal basin can be considered for:

Ultrasound surveillance in stage I or II melanoma is superior to the clinical examination of the regional lymph node, but the long-term survival benefit of ultrasound surveillance is unknown [8]. Only a few patients benefit from earlier detection of lymph node metastasis or avoidance of unnecessary surgery, and some undergo unnecessary surgery for suspicious findings [8].

Isolated metastases detected by surveillance or staging imaging can be potentially cured by surgical resection, radiotherapy, or systemic therapies [18–20], and patients have superior survival rates with modern therapies [21–23].

Without a randomised trial, it is difficult to prove that melanoma survival is superior in those who have undergone imaging.

Even after negative imaging, patients or their partners detect the majority of recurrences in melanoma as they are often visible or palpable within the skin or lymph nodes [30,31].

There is a risk that surveillance imaging may detect non-specific lesions or result in false-positive findings for metastasis [1,41].

Multiple studies have evaluated the overall accuracy of PET-CT staging and surveillance.

The optimum frequency for surveillance scans — and for how long — are unknown.