Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Created 2008.

Note: the diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis are not included in this topic.

Urticaria is composed of weals: recurrent transient oedematous dermal papules and plaques, individual lesions persisting less than 24 hours. Weals may be asymptomatic but are often intensely itchy or sting and burn. Angioedema results from oedema of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and accompanies urticaria in 40% of cases or occurs on its own in 10%.

Urticaria may be acute (<6 weeks duration) or chronic (>3 months). Several factors (cytokines and chemokines) are implicated in the activation of mast cells receptors. Immunologic or non-immunologic mechanisms elicit mediator releases and inflammatory activities inducing urticaria lesions.

The cause is unknown in most cases but some are due to IgE-mediated Type 1 hypersensitivity reactions i.e. allergy and may progress to anaphylaxis – the rest are non-allergic in origin.

| Allergens |

|---|

|

| Non-allergic causes |

|

If intermittent angioedema occurs without urticaria, an ACE inhibitor may be responsible. Rarely, it is caused by inherited or acquired defects in C1 esterase inhibitor.

Acute urticaria Chronic urticaria Giant urticaria

Anti-FceRI autoantibodies have been detected in about 60% of chronic urticaria cases, confirming chronic or ordinary urticaria to be an autoimmune disease in the majority of cases. It may be associated with chronic infection in others (helicobacter, candida, sinusitis, dental infection).

Angioedema may rarely be due to decreased C1-esterase inhibitor; in such cases, there may be a family history. The presence of urticaria rules this out.

In many cases, no cause is found after careful history and investigation.

Physical urticaria accounts for 50% of cases of urticaria and may coexist with idiopathic chronic urticaria. Physical urticaria results in localised short-lasting weals (less than one hour). Physical urticaria may be due to:

Dermographism

Aquagenic urticaria

Contact urticaria

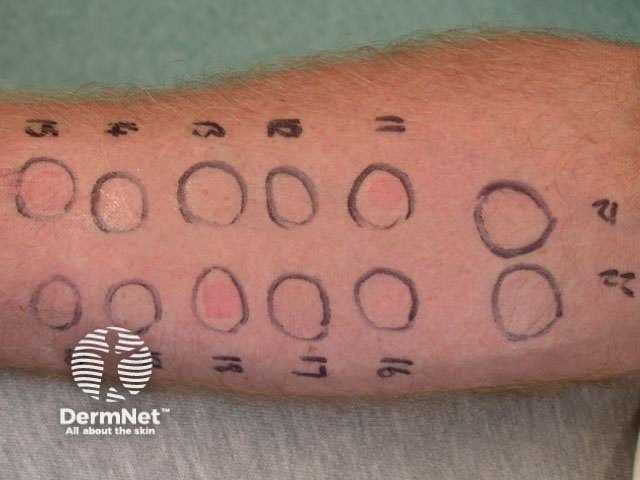

In most cases, no investigations are warranted as the diagnosis is made by history and examination. In some cases, a blood count is warranted (eosinophilia may point towards a drug allergy or parasitic infestation). Prick tests are rarely helpful but may be warranted for some food-related reactions. Interpretation can be difficult.

If the patient appears to have a severe allergy, for example, a food-related or food and exercise-related anaphylaxis, consider RAST Tests for potential causes particularly peanuts.

The autologous serum skin test can be used to identify the autoimmune origin.

If angioedema in the absence of urticaria is recurrent, complement levels should be measured. C1 esterase inhibitor defects are associated with low levels of C4.

Management should include avoidance of known precipitants. Antihistamines reduce itching, and to a lesser degree wealing, in most cases. However, it may take several days for antihistamines to take effect in acute urticaria. Newer generation antihistamines available in New Zealand include:

The dose may need to be increased. Conventional antihistamines such as promethazine, chlorpheniramine, azetidine and trimeprazine are less expensive and are sometimes prescribed for night sedation. They may cause anti-adrenergic and anticholinergic side effects, which may be particularly troublesome and prolonged in the elderly.

Oral steroids are often prescribed for 4 or 5 days for acute urticaria that is resistant to antihistamines (40mg daily), but they should not be prescribed in most cases of chronic urticaria.

Many other medications are used in chronic urticaria and are occasionally helpful, including:

Phototherapy or photochemotherapy (PUVA) may also be of benefit in selected patients.

What is the evidence that specific diets are useful in the management of chronic urticaria (e.g. avoiding salicylates and food additives, or low fat)?

Information for patients