Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Donna Bartlett, Medical Writer, Allori, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Adjunct A/Prof Dr Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell/Maria McGivern. December 2018.

This article was supported by an educational grant from Novartis, distributors of Xolair™ in New Zealand and Australia. Xolair is not indicated for the treatment of chronic inducible urticaria in either country. Sponsorship does not influence content.

Introduction - urticaria

Introduction - chronic urticaria

Introduction

Demographics

Clinical features

Causes

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Pharmacological treatment

Outcome

Urticaria is a condition characterised by the presence of weals (hives) or angioedema (swelling in the skin).

Urticaria affects up to one in four people at some time in their lives and is classified by duration, acute or chronic, and cause, whether spontaneous or inducible.

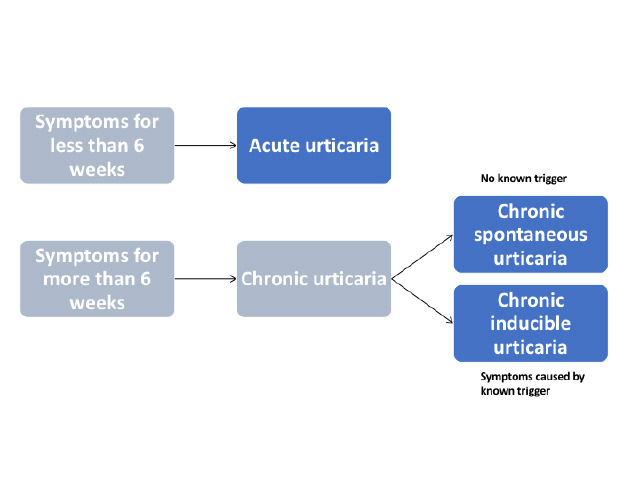

Acute urticaria is the daily or episodic occurrence of weals, angioedema, or both for less than 6 weeks. Causes can include infections and allergies, but more often, the cause is unknown.

Figure 1 - Classification of urticaria

Spontaneous urticaria

Angioedema

Dermographism

Chronic urticaria is the daily or episodic occurrence of weals, angioedema, or both for 6 weeks or more. Chronic urticaria can persist for a duration ranging from a few months to many years.

International guidelines have recently been published for the classification, diagnosis, and management of chronic urticaria, based on a consensus from multiple national and international societies.

Chronic urticaria is either spontaneous or inducible; both types may co-exist in one patient. (See DermNet's page on Chronic spontaneous urticaria).

Chronic inducible urticaria is chronic urticaria that has an attributable cause or trigger and is classified according to the stimulus that provokes weals to develop. Commonly, these stimuli that provoke weals to develop include stroking or scratching the skin (dermographism), exercise, and emotional upset (cholinergic urticaria).

Less common forms of chronic inducible urticaria are triggered by cold, heat, pressure, sunlight (solar urticaria), contact with water or various chemicals (contact urticaria), or vibration.

Chronic urticaria is reported to affect 1.8% of the population. The prevalence of chronic inducible urticaria is approximately 0.5% (15–25% of all cases of chronic urticaria).

Women experience urticaria and chronic urticaria almost twice as often as men. Although urticaria in children is common, they are more likely to present with chronic spontaneous urticaria than with chronic inducible urticaria.

Chronic inducible urticaria usually presents with weals. Weals can appear on any site of the body.

Characteristically, weals are:

Vibratory angioedema can very rarely be induced within a few minutes of exposure to a vibratory stimulus. Delayed pressure can lead to urticaria and angioedema.

Symptoms are usually confined to skin areas that are exposed to a specific trigger. Individual patients may exhibit two or more subtypes of chronic inducible urticaria.

Linear weals in dermographism

Round and linear weals in dermographism

Diffuse weal from ice cube test in cold urticaria

Urticaria is a mast cell-driven disease. Activated mast cells release histamine along with other mediators, such as platelet-activating factor and cytokines, resulting in sensory nerve activation, vasodilation, plasma extravasation, and recruitment of cells to the urticarial lesion. Mast cells can be activated by many different molecules in urticaria, but generally, these are not well defined.

Weals and angioedema are induced by environmental or physical stimuli in chronic inducible urticaria. Different types of inducible urticaria and their triggers include:

The burden of chronic urticaria is substantial for patients, their families and carers, the healthcare system, and society. Chronic urticaria can result in sleep deprivation, anxiety, depression, lack of energy, and social isolation and result in a significant deterioration in the quality of life.

Chronic inducible urticaria is diagnosed through the taking of a careful history and examination; this diagnosis is based on a history of daily or episodic weals for more than 6 weeks that have been induced by an external stimulus.

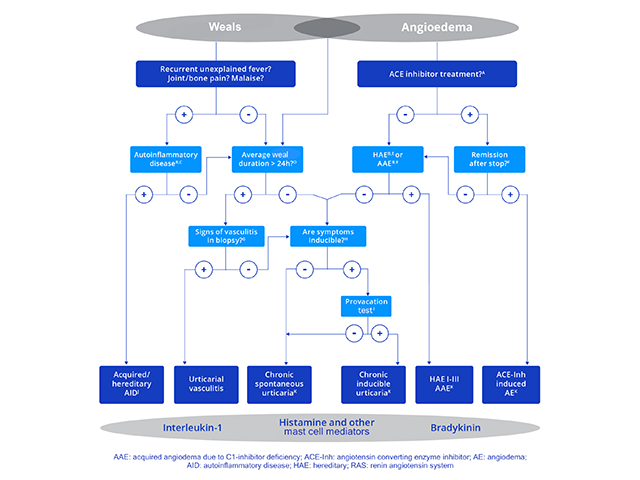

International guidelines provide a diagnostic algorithm for chronic urticaria (see figure 2). The diagnosis of chronic inducible urticaria relies on provocation testing and then compiling a thorough history covering:

Figure 2 - Diagnostic algorithm for chronic urticaria

Credit: Zuberbier et al, Allergy 2018.

The consensus recommendations for diagnostic testing and management of chronic inducible urticaria can be used to identify the subtype of chronic inducible urticaria and to assess disease activity.

Provocation testing is used to determine the relevant triggers and to assess trigger thresholds. Provocation testing in positive patients usually results in the development of urticaria within a few minutes. One exception is delayed pressure urticaria, where it may be necessary to wait several hours for a response.

In patients with negative provocation responses, where chronic inducible urticaria is strongly suspected from the patient’s history, the test should be repeated. Ideally, the test should be conducted on a skin site that has previously been affected, although testing should not be done if weals have occurred in this site within the previous 3 days.

The results of provocation tests can be affected by medication; therefore, symptomatic treatment should be ceased before testing if possible. Antihistamines should be stopped 3 days before testing, and systemic glucocorticoids 7 days before testing.

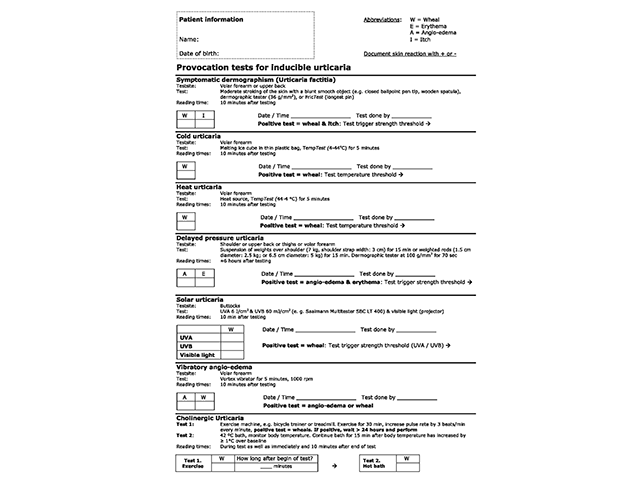

A sample form for the documentation of provocation testing is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3 - Provocation tests for inducible urticaria

Credit: Magerl M, et al. Allergy 2016.

The differential diagnosis depends on the specific type of chronic inducible urticaria and includes other forms of inducible and spontaneous urticaria, which may co-exist.

In addition to diagnosis, trigger threshold measurements are also used during treatment to measure ongoing disease activity and response to treatment.

The Urticaria Control Test (UCT) is useful in the assessment of patients’ disease status and is validated to determine the level of disease control in both chronic spontaneous urticaria and chronic inducible urticaria. The UCT has only four items with a clear cut-off for ‘well controlled’ versus ‘poorly controlled’ disease, making it useful in routine clinical practice.

The Angioedema Activity Score (AAS) allows the patient to score each of five key factors relating to their symptoms from 0 to 3 (giving a daily score of 0–15). Daily AAS can be summed to provide 7-day (AAS7), 4-week (AAS28), and 12-week (AAS84) scores.

Validated instruments can be used to assess the emotional impact of chronic urticaria and the effect on the patient’s quality of life, such as the Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU-Q2oL) and the Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE-QoL).

Treatment aims to control symptoms.

The approach to the management of chronic inducible urticaria can involve:

It is often difficult for patients with chronic inducible urticaria to completely avoid the physical stimuli that trigger wealing. It is recommended that patients minimise exposure to triggers as much as possible, although the induction of tolerance (described below) requires daily exposure to a trigger.

Inducing tolerance can be useful in cold urticaria, cholinergic urticaria, and solar urticaria. Tolerance induction lasts only a few days, and consistent daily exposure is required to maintain tolerance.

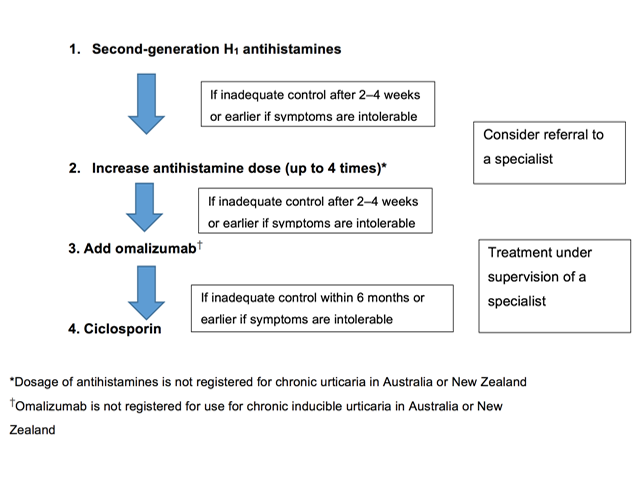

An algorithm to treat chronic urticaria is included in the international guidelines (see figure 4), these guidelines should be used with caution in children and pregnant/lactating women. Drugs that are contraindicated in pregnancy should not be used.

Treatment should be continued as required until the urticaria has cleared up.

Figure 4 - Pharmacological treatment algorithm for chronic urticaria

Credit: Zuberbier et al, Allergy 2018.

Some forms of chronic inducible urticaria are mediated by histamine. Intermittent or continuous treatment with H1-antihistamines is supported by clinical trial data.

Non-sedating antihistamines are preferred to older antihistamines, which have anticholinergic effects and sedative actions. First-line symptomatic treatment for chronic inducible urticaria includes:

Terfenadine and astemizole are no longer available in New Zealand or Australia because they are cardiotoxic in combination with ketoconazole or erythromycin.

If standard doses are not effective, the doses of bilastine, loratadine, cetirizine, desloratadine, ebastine, fexofenadine, levocetirizine and rupatadine can be increased up to four-fold (note that some of these agents are not available and the higher doses are not licensed in New Zealand or Australia).

Most patients with chronic inducible urticaria who do not respond to standard doses of antihistamines will benefit from up-dosing, but antihistamines are not always effective. Localised heat urticaria, aquagenic urticaria, and vibratory urticaria rarely respond to antihistamines.

About one-third of patients continue to have symptoms despite maximal tolerated daily doses of antihistamine. Patients with refractory chronic inducible urticaria should be referred to a dermatologist, immunologist, or medical allergy specialist.

Omalizumab has been reported to be effective in chronic inducible urticaria, including cholinergic urticaria, cold urticaria, solar urticaria, heat urticaria, symptomatic dermographism, and delayed pressure urticaria.

Note: Omalizumab is not indicated for the treatment of patients with chronic inducible urticaria in New Zealand or Australia.

No published trials have specifically investigated the use of ciclosporin in patients with chronic inducible urticaria, although a case-series (n=100) investigating its use in the management of chronic spontaneous urticaria included patients that also had chronic inducible urticaria (45% of cases). Control was achieved with ciclosporin or omalizumab in some cases refractory to antihistamines.

Note: Ciclosporin is not indicated for the treatment of patients with chronic inducible urticaria in New Zealand or Australia.

Phototherapy has been successful in the treatment of patients with chronic inducible urticaria, particularly in patients with dermographism. The most common form of phototherapy used is narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy.

There is little evidence to support any other treatments for chronic inducible urticaria.

Immunomodulatory treatments may be of value to individual patients in particular clinical situations (eg, dapsone for cold urticaria).

Chronic inducible urticaria may resolve with treatment of symptoms and avoidance of physical stimuli that trigger the urticaria. However, in many patients, the threshold for the relevant physical trigger is low and total avoidance of symptoms is almost impossible.