Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Donna Bartlett, Medical Writer, Allori, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Adjunct A/Prof Dr Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell/Maria McGivern. December 2018.

This article was supported by an educational grant from Novartis, distributors of Xolair™ in New Zealand and Australia. Sponsorship does not influence content.

Introduction - urticaria

Introduction - chronic urticaria

Clinical features

Causes

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

Urticaria is a condition characterised by the presence of weals (hives) and angioedema.

Weals are accompanied by angioedema in up to 40% of cases, but angioedema may occur on its own in some people.

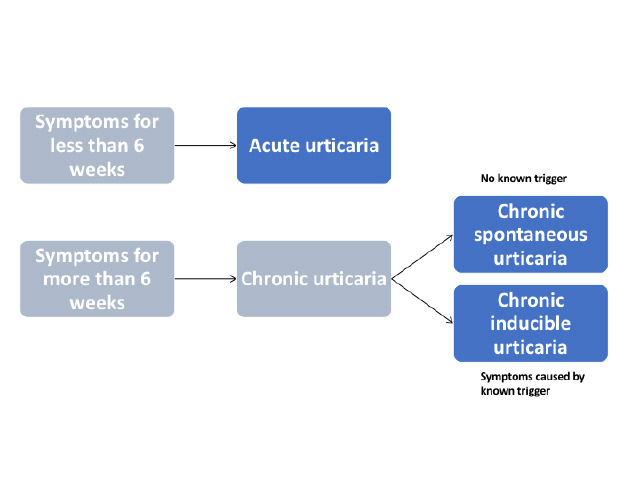

Urticaria affects up to one in four people at some time in their lives and can be classified by duration, acute or chronic, and by cause, whether spontaneous or inducible. Two or more different subtypes of urticaria may co-exist in one person.

Acute urticaria is the daily or episodic occurrence of weals, angioedema, or both, for under 6 weeks. There are multiple possible causes, including infections or allergies, but it is often idiopathic.

Figure 1 - Classification of urticaria

Adapted from Zuberbier T et al, 2018.

Spontaneous urticaria

Spontaneous urticaria

Severe lip angioedema

Chronic urticaria is the daily or episodic occurrence of weals, angioedema, or both, for 6 weeks or more. Chronic urticaria can persist for 1–5 years, sometimes longer.

International guidelines for the classification, diagnosis, and management of chronic urticaria have recently been published based on a consensus from multiple national and international societies.

Chronic urticaria may be classified as either spontaneous or inducible, and both types may co-exist in one patient. This article is about chronic spontaneous urticaria. (See DermNet's page on Chronic inducible urticaria).

Chronic spontaneous urticaria refers to chronic urticaria that has no specific cause or trigger. Weals are present on most days of the week for 6 weeks or more.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria was previously referred to as chronic idiopathic urticaria. This term is no longer used as many cases have an autoimmune basis.

Estimates of the incidence of chronic urticaria range from 0.05% to 2% of the population in the US, and up to 20% of the population in Thailand.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria is characterised by the presence of weals and angioedema.

Weals can affect any site on the body and tend to be distributed widely.

Spontaneous urticaria

Spontaneous urticaria

Spontaneous urticaria

See more images of urticaria and angioedema.

Angioedema is more often localised.

Lid angioedema - there was typical urticaria elsewhere on the body

Unilateral lid angioedema

Angioedema of the right hand

Chronic spontaneous urticaria is unpredictable and debilitating. The weals are more persistent in chronic spontaneous urticaria than in chronic inducible urticaria, but each tends to resolve or alter in shape within 24 hours. They may occur at certain times of the day.

Some patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria report associated systemic symptoms. These may include:

There are several validated systems to assess the activity and control of urticaria.

Disease activity in chronic spontaneous urticaria can be assessed with the 7-day Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7), a simple, validated scoring system based on the assessment of key urticaria signs and symptoms — weals and pruritus — that are documented by the patient. The daily weal and pruritus scores are added up for 7 days; the maximum score is 42.

The score for weals + the score for itch = daily score. Repeat daily for 7 days and add up the scores for UAS7.

Score |

Weals |

Score |

Pruritus |

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

None |

0 |

None |

1 |

Mild ( 20 weals/24 hours) |

1 |

Mild (present but not annoying or troublesome) |

2 |

Moderate (20–50 weals/24 hours) |

2 |

Moderate (troublesome but does not interfere with normal daily activity or sleep) |

3 |

Intense (> 50 weals/24 hours or large confluent area of weals) |

3 |

Intense (severe pruritus that is sufficiently troublesome to interfere with normal daily activity or sleep) |

The Urticaria Control Test (UCT) is useful in the assessment of the patient’s disease status and is validated to determine the level of disease control in both chronic spontaneous urticaria and chronic inducible urticaria. The UCT has four items with a clear cut-off for ‘well controlled’ versus ‘poorly controlled’ disease, making it useful in routine clinical practice.

The Angioedema Activity Score (AAS) allows the patient to score each of five key factors relating to their experience of angioedema from 0 to 3 (giving a daily score of 0–15). Daily AAS can be summed to provide 7-day (AAS7), 4-week (AAS28), and 12-week (AAS84) scores.

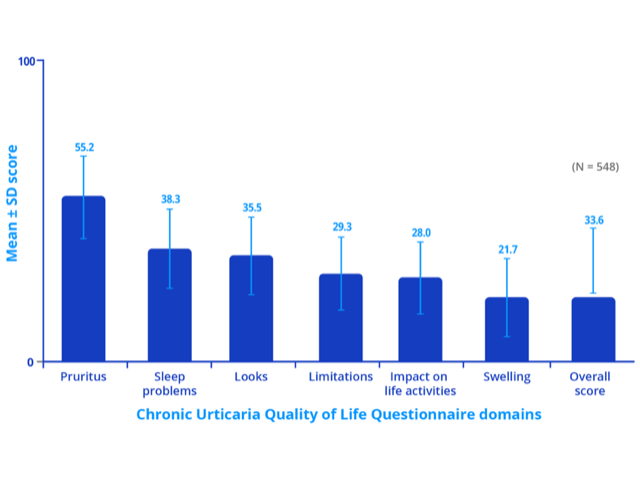

Current international guidelines recommend validated instruments to assess the emotional impact of chronic urticaria and the effect on the patient’s quality of life, such as the Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU-Q2oL) and the Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE-QoL).

Urticaria is a mast cell-driven disease. Activated mast cells release histamine along with other mediators, such as platelet-activating factor and cytokines, resulting in sensory nerve activation, vasodilation, plasma extravasation, and recruitment of cells to the urticarial lesion. Many different molecules can activate mast cells in urticaria, but generally, these are not well defined.

By definition, chronic spontaneous urticaria has no known trigger. Causes include:

Chronic spontaneous urticaria may be due to a type I allergy in exceptionally rare cases.

There is a strong association between chronic spontaneous urticaria and other immune disorders, in particular, autoimmune thyroid disease. Thyroid autoantibodies are the most common laboratory abnormalities associated with chronic spontaneous urticaria, with most studies reporting elevated levels in 10% or more of affected patients. Thyroid dysfunction rates are also increased in people with chronic spontaneous urticaria, with hypothyroidism, and Hashimoto thyroiditis observed more commonly than hyperthyroidism and Graves disease.

The frequency of underlying causes varies in different studies of chronic spontaneous urticaria, reflecting regional differences in diet or the prevalence of infections.

Patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria may experience sleep deprivation, anxiety, depression, lack of energy, and social isolation. These can result in a significant deterioration in the patient's quality of life (see figure 2). Chronic spontaneous urticaria is unpredictable and can disrupt the patient’s normal daily activities.

Figure 2 - Impact of chronic spontaneous urticaria on quality of life, sleep and daily activities

Note: Higher score indicates greater impairment of quality of life.

Credit: Adapted from Maurer M, et al. Allergy 2017; 72: 2005–16.

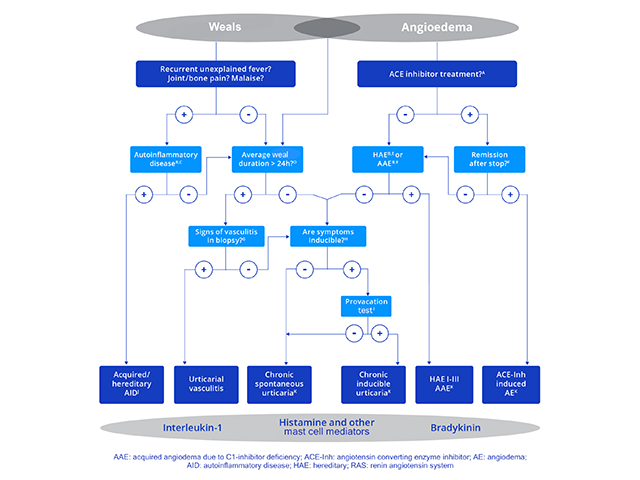

Chronic urticaria is diagnosed through the taking of a careful history and examination; this diagnosis is based on a history lasting over 6 weeks of daily or episodic weals that last less than 24 hours without the presence of physical trigger factors.

International guidelines provide a diagnostic algorithm for chronic urticaria (see figure 3). The diagnosis of chronic spontaneous urticaria relies on compiling a thorough history covering:

The international guidelines recommend limiting investigations in most patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria to differential blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Further diagnostic measures are based on patient history and examination, especially in patients with long-standing and uncontrolled disease.

Figure 3 - Diagnostic algorithm for chronic urticaria

Credit: Adapted from Zuberbier T, et al. Allergy 2018.

International guidelines recommend that differential diagnoses be considered in all patients with signs or symptoms suggestive of chronic urticaria based on the diagnostic algorithm. These include:

There is no ‘cure’ for chronic urticaria. The goal of treatment is to achieve symptom-free control.

The approach to the management of chronic spontaneous urticaria can involve:

Often the management for chronic inducible urticaria and chronic spontaneous urticaria will overlap.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria is often reported to be associated with a variety of inflammatory or infectious diseases. Any identified infectious diseases (eg, H. pylori infection, bacterial infections of the nasopharynx, or bowel parasites) and chronic inflammatory processes (eg, gastritis, reflux oesophagitis, and inflammation of the bile duct or gallbladder) should be treated.

Plasmapheresis can reduce functional autoantibodies and has been shown to provide temporary benefit in some autoantibody-positive patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria who have not responded to any other forms of treatment.

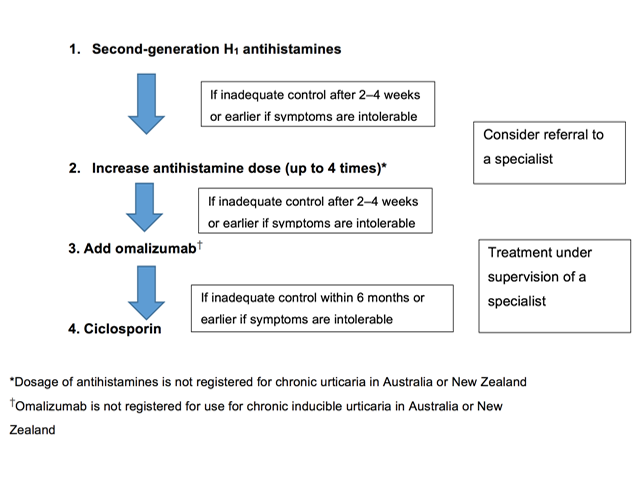

About one-third of patients continue to have symptoms despite maximal tolerated daily doses of non-sedating antihistamine.

An algorithm for the symptomatic treatment of chronic urticaria is included in the international guidelines (see figure 4). The algorithm should be used with caution in children with chronic urticaria and in pregnant/lactating women as drugs contraindicated in pregnancy should not be used. Treatment should be continued until remission occurs.

Figure 4 - Pharmacological treatment algorithm for chronic urticaria

Credit: Adapted from Zuberbier T, et al. Allergy 2018.

Many symptoms of urticaria are mediated by the actions of histamine on H1-receptors located on endothelial cells (causing the weals) and on sensory nerves (causing neurogenic flare and pruritus). Continuous treatment with H1-antihistamines is supported by clinical trial data. In some forms of physical urticaria, such as cold urticaria, ‘as required’ treatment may be appropriate.

Second-generation antihistamines are recommended in preference to first-generation antihistamines, as the latter have anticholinergic effects and sedative actions, and they interact with alcohol and many drugs that affect the central nervous system. Second-generation non-sedating antihistamines are the first-line symptomatic treatment for urticaria because of their good safety profiles. Those studied in the treatment of chronic urticaria include:

Terfenadine and astemizole are no longer available in New Zealand or Australia and should not be used as they are cardiotoxic in combination with ketoconazole or erythromycin.

A number of small randomised trials have confirmed the improved efficacy of higher doses of second-generation antihistamines at up to four times the recommended doses of bilastine, cetirizine, desloratadine, ebastine, fexofenadine, levocetirizine, and rupatadine (some of these agents are not available and higher doses are not licensed in New Zealand or Australia). The majority of patients with urticaria who are not responding to standard doses will benefit from up-dosing of antihistamines.

Patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria that have failed to respond to maximum-dose second-generation oral antihistamines taken for 4 weeks should be referred to a dermatologist, immunologist or medical allergy specialist.

Omalizumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to free IgE, reducing the amount of IgE available in the blood and subsequently the skin. This leads to downregulation of surface IgE receptors, decreasing downstream signalling, and resulting in suppressed activation of mast cells and basophils and in reduced inflammatory responses.

Omalizumab has been shown to be effective and well-tolerated in the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Phase III studies have demonstrated efficacy at doses from 150 mg to 300 mg every 4 weeks independent of total serum IgE levels or body weight. Omalizumab improves angioedema, improves quality of life, is suitable for long-term use, and treats relapse after discontinuation.

The recommended dose for the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria is 300 mg by subcutaneous injection every 4 weeks. Some patients may achieve control of their symptoms with a dose of 150 mg every 4 weeks.

Omalizumab is indicated in New Zealand and Australia for adults and adolescents (≥ 12 years of age) with chronic spontaneous urticaria who remain symptomatic despite H1-antihistamine treatment. As of August 2018, it is currently listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme in Australia for patients with severe chronic spontaneous urticaria provided specific criteria are met. Omalizumab is funded for use in chronic spontaneous urticaria in New Zealand under Special Authority criteria (refer to PHARMAC for details).

Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin 4 (IL-4) and interleukin 13 (IL-13) signalling. It has demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing itch and urticaria in antihistamine-refractory CSU. In 2025, dupilumab was approved by the FDA for treatment in adults and adolescents ≥12 years old with CSU who remained symptomatic despite H1 antihistamine treatment.

Remibrutinib and fenebrutinib are oral BTK inhibitors that have clinically demonstrated fast and sustained efficacy in CSU, with favourable safety profiles. Remibrutinib is FDA-approved for use in adults unresponsive to H1 antihistamine therapy. Rilzabrutinib is currently under investigation with promising initial results.

Ciclosporin is a calcineurin inhibitor and has a moderate direct effect on mast cell mediator release. The efficacy of ciclosporin in combination with a second-generation H1-antihistamine has been shown in placebo-controlled trials in chronic spontaneous urticaria. It is not recommended as a standard treatment due to the risk of significant adverse effects. Ciclosporin should be reserved for patients with severe refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Other agents have been used off-label for the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria but have little evidence to support them. These treatments include:

These treatments may be of value to individual patients in particular clinical situations.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria has a high rate of remission; this rate of remission was up to 80% in 12 months in one population study. However, symptoms were reported to last for longer than 1 year in up to 20% of patients and for more than 5 years in 11.3% of patients in another study.