Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Created 2008.

About 2,000 new cases of invasive malignant melanoma are diagnosed each year in New Zealand, with 244 deaths in 2001. The age-standardised rate was 35.8 (male) and 32.0 (female) per 100,000 in 2003, among the highest in the world.* The number of in situ cases is unknown but probably accounts for more than another 1000 cases. Melanoma is the most common registered cancer and the fourth most common cause of cancer death among the 15-44 year age group. The pattern of incidence is 10-30% in young adults, 30-40% in middle age and 40-55% in old age.

The lifetime risk in the fair-skinned New Zealand population is estimated to be 1:25. About 14% of patients with melanoma eventually die of their disease; many deaths occur in young adults. Reported age-standardised annual rate in Auckland 1995-1999 was 56.2/100,000** and may be even higher in the far North and Bay of Plenty (personal communication).

* Cancer statistics New Zealand Health Information Service (accessed April 2006)

**Jones WO, Harman CR, Ng AK, Shaw JH. Incidence of malignant melanoma in Auckland, New Zealand: highest rates in the world. World J Surg. 1999 Jul;23(7):732-5. Medline.

Genetic factors (10%) and sun exposure are clearly important in melanoma development. Cell cycle control and transcriptional control mechanisms are disordered in the pathogenesis of the disease.

The main gene involved in about 30% of familial melanoma cases and 30% of sporadic cases is, CDKN2A or INK4a/ARF. It is found on chromosome 9p21 and codes for p16 and p14ARF proteins. These proteins prevent cell cycle progression through a complex process involving p53. The result of mutation is that mutagenic DNA persists and the cell keeps on dividing. Germline mutations in CDKN2A are present in many large multi-case melanoma families. Several other abnormal genes on various chromosomes have been found in some individuals and families with melanoma.

It is believed that melanoma arises from multiple and heterogeneous clones, thus requiring a variety of approaches to treatment. The latest theories indicate that melanoma is derived from transformed stem cells in the hair follicle (lentigo maligna), the epidermis (superficial spreading melanoma) or upper dermis (nodular melanoma).[1]

Melanoma is an immunogenic tumour, at least in its early phases. Complete or partial regression is reported in 50% of primary tumours and can result in halo naevi and distant loss of pigment that is vitiligo-like. The major melanoma antigens include mutated p16 (CDKN2A), MAGE-3 (44%), Melan A/MART-1 (88%), tyrosinase (94%) and several others. Their expression on the cell surface can be observed by immunohistochemistry. Once antigen-presenting cells from the tumour site have reached a draining lymph node, melanoma-specific T cells are activated. These activated CD8+ cytotoxic T cells can recognise the antigens and kill the tumour cells but many escape detection. Tumour-specific antigens disappear and immuno-inhibitory cytokines are released in advanced tumours.

Ultraviolet radiation, especially when associated with sunburns, probably plays an important role in about 90% of melanoma in New Zealand, possibly especially when this sunburn occurs during childhood. Exposure to indoor tanning facilities is also associated with an increased risk of melanoma. The mechanisms are uncertain and may involve ultraviolet (UV)-B, UV-A and visible light.

As most melanoma can be specifically attributed to sun exposure, particularly to sunburn in childhood, the most important strategy should be to protect children (and adults) from excessive sun exposure.

Lifelong protection from sun exposure should include:

However, the data regarding the use of sunscreens is difficult to interpret because there is an association with increased melanoma risk. This is probably because:

Melanoma may be seen at all ages, but generally increases with age. It has an equal incidence in males and females in New Zealand.

The following features identify high-risk individuals:

Familial dysplastic naevus syndrome refers to the association of primary melanoma with atypical naevi affecting several family members. An individual with atypical naevi from an affected family has 10-100% risk of primary melanoma. Tests of genetic markers such as CDKN2A are not routinely available at this time (2005). Melanoma may be associated with DNA repair defects (xeroderma pigmentosum) but these autosomal recessive disorders are extremely rare in New Zealand.

Although increasing numbers of atypical naevi are associated with increased melanoma risk, baseline photography with follow-up has demonstrated that between one-third and two-thirds of the melanomas arise as new lesions and the rest arise from dysplastic naevi.

Melanoma prognosis mainly depends on the depth of the tumour in mm at the time of excision (Breslow thickness) and level of invasion (Clark's levels). Therefore, early identification of melanoma is potentially life-saving.

The pTNM classification system for stage I and II melanoma has been in general use until recently.

| pTis | Melanoma in situ |

| pT1 | Melanoma <0.75 mm thick |

| pT2 | Melanoma >0.75 mm <1.5 mm thick |

| pT3a | Melanoma >1.5 mm <3.0 mm thick |

| pT3b | Melanoma >3.0 mm <4.0 mm thick |

| pT4 | Melanoma >4.0 mm thick |

A new staging classification is now recommended, which was introduced by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) in 2000. It is characterised into local, regional and distant disease.

Local disease is classified using Breslow depth. Clark's level is only included for T1 tumours.

| Tis | Melanoma in situ | |

| T1 | Breslow depth <1 mm | a: Without ulceration and level II/III b: With ulceration or level IV/V |

| T2 | Breslow depth >1 mm <2 mm | a: Without ulceration b: With ulceration |

| T3 | Breslow depth >2 mm <4 mm | a: Without ulceration b: With ulceration |

| T4 | Breslow depth >4 mm | a: Without ulceration b: With ulceration |

The number of regional lymph nodes metastases is classified N1-N3 and distant metastases M1a-M1c.

First, take a relevant history.

The entire skin surface should be examined.

Consider melanoma in all cases of pigmented or changing lesions on the skin in adults. In children, melanoma is rare below the age of 12 but may be impossible to distinguish clinically from Spitz naevus. In young adults, less than 1% of new naevi, and less than 3% of changing naevi are melanoma. In those over 50, 30% of new naevi and 22% of changing naevi have been reported to be melanoma. In males, 40% of melanomas occur on the trunk. In females, a similar proportion occurs on the legs. In ethnically dark-skinned individuals, most melanomas arise on palm, sole or nail bed.

Examine the lesion with good light and magnification.

Characteristics of melanoma:

The American ABCDE criteria of melanoma and the British 7-point checklist are useful guides for the evaluation of pigmented lesions.

| A: | Asymmetry of shape and pigment pattern |

| B: | Well-defined irregular border |

| C: | Variation in colour, often with a red halo |

| D: | Diameter over 6mm (but it is possible to diagnose smaller melanomas) |

| E: | Evolving (change in size, shape or colour), or Elevation (but early melanomas are flat) |

| Major features | Minor features |

|---|---|

|

|

These features may miss nodular melanoma (symmetrical, dome-shaped, single colour) and amelanotic melanoma (pink or red without pigmentation).

Some subjects with sun damage or atypical naevi have several or many lesions with irregular shape and colour. It may be prudent to remove the most odd-looking lesion for histopathology. If it is reported to be banal, there may be no need to remove any others. If in doubt, refer the patient to a dermatologist for evaluation, or arrange whole body mole mapping.

If you have relevant training and experience, use dermoscopy to examine a broad selection of benign lesions as well as clinically suspicious lesions.

Biopsy of pigmented lesions on the basis of suspicious clinical and/or dermatoscopic features requires complete excision with a 2mm margin. An expert should normally be consulted following the diagnosis of melanoma (dermatologist, plastic or general surgeon).

Nodular melanoma (15-30% of cases) shows vertical growth histologically and tends to enlarge more rapidly and deeply than superficial spreading melanoma (0.5 mm per month). They may be blue, black, red (60%) or skin coloured. They may ulcerate or bleed spontaneously.

Black nodular melanoma Amelanotic nodular melanoma Ulcerated nodular melanoma Ulcerated nodular melanoma

Superficial spreading melanoma (SSM, 60–70% of cases) shows horizontal growth histologically and can be in situ or invasive. Generally, the ABCDE criteria characteristics are helpful for diagnosis. However, the lack of pigmentation in amelanotic melanoma means it is frequently misdiagnosed and removed late. Nodular melanoma can arise within superficial spreading melanoma.

Typical SMM SSM with regression Large SSM mistaken for a bruise Partially amelanotic SSM SSM with marked regression SSM in situ Amelanotic melanoma SSM in situ

Acral lentiginous melanoma (5–10% of cases) arises on the thickened skin of the soles and palms. It may also arise under the nails (subungual melanoma), where it first appears as an irregular broadening band of pigmentation, often with the pigmentation of adjacent nail fold (Hutchinson's sign). Acral lentiginous melanoma is the predominant melanoma of non-whites.

Acral lentiginous melanoma Acral lentiginous melanoma Subungual melanoma Amelanotic subungual melanoma

Subungual melanoma is often diagnosed late after the nail has split or been lost. It has a poor prognosis and is treated by amputation of the distal phalanx. It can be difficult to distinguish from haemorrhage, especially if there is no history of trauma. Pigmentation in the skin around the nail is characteristic (Hutchinson's sign).

Lentigo maligna (LM, Hutchinson's freckle, 5–15% cases) is a common pigmented lesion on the exposed skin of the older patient and is melanoma in situ arising in sun-damaged skin (face or neck). Complete surgical excision is recommended but not always practical. In some very elderly patients, careful observation is acceptable. The role of imiquimod in such cases is under investigation, as the clinical and histological resolution in some lesions has been reported with prolonged use.

The development of a papule or nodule in about 5% of LM is due to invasive disease (lentigo maligna melanoma).

Longstanding LM LM with amelanotic areas Nodule within LM melanoma Nodule within LM melanoma

Anal melanoma Vulval melanoma Inguinal melanoma Childhood melanoma Malignant blue naevus Desmoplastic melanoma

These variants of melanoma have a high rate of recurrence and metastasis.

The histopathological request form should include clinical information including size, colour and duration of the lesion and differential diagnosis. When more than one lesion is excised, make sure all specimens are carefully placed in separate accurately labelled containers.

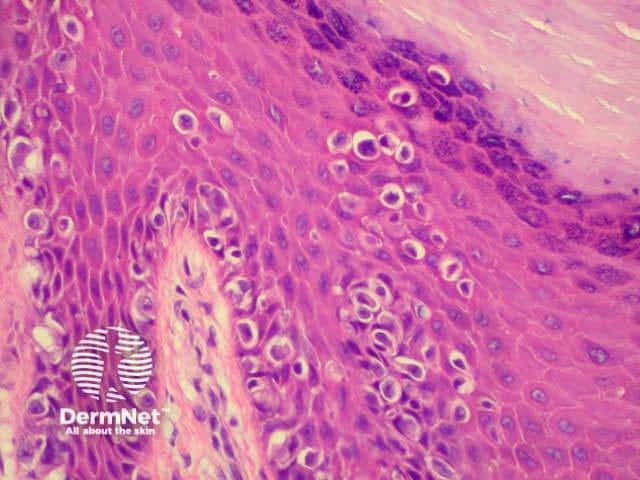

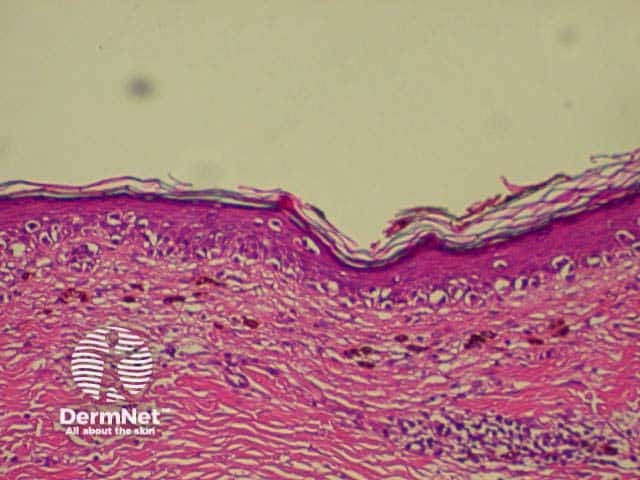

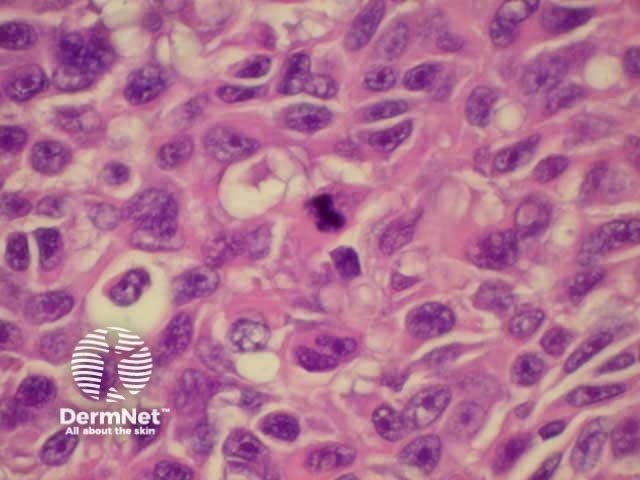

The diagnosis is made from the architectural pattern of the lesion (asymmetrical, poorly circumscribed and with variable nests of melanocytes) and cytomorphology (spindled, pagetoid, small and large round-shaped, polygonal, multinucleate and/or with dendritic characteristics).

Melanoma in situ is characterised by atypical melanocytes in the basal layer and scattered higher in the epidermis (pagetoid spread). Invasive melanoma refers to neoplastic melanocytes found in the papillary dermis, either as nests or as single cells.

The pathologist's report should include as a minimum:

In addition, the report may refer to the presence of an associated melanocytic naevus, to tumour infiltrating lymphocytes, regression, vascular invasion and microscopic satellites. The growth pattern may be radial (corresponding to superficial spreading clinical subtype) or vertical (nodular clinical subtype).

In difficult cases, extra immunohistochemistry stains such as S-100 and HMB45 may be used to identify the melanocytic origin of a tumour. These employ monoclonal antibodies against melanoma-associated antigens.

Acral lentiginous melanoma. Melanoma cells infiltrating up through epidermis. Note thick stratum cor Lentigo maligna. Proliferation of abnormal melanocytes along the basal layer of a thinned, sun-damag High power view of melanoma cells. Note mitosis in the centre of the image.

Clinically typical melanoma should be removed as soon as it can be arranged. The suspicious lesion should be excised completely with a 2 to 3 mm surgical margin. The diagnosis of melanoma should be confirmed by histological examination of the entire specimen.

Management options for lesions in which the diagnosis is in doubt may include:

Incisional biopsies are not recommended as they may miss a malignant focus within a benign lesion and because early melanoma can be subtle histologically. However, specialists may choose to biopsy some lesions such as a large benign-looking facial freckle prior to cryotherapy, or a clinically typical melanoma to plan definitive surgery. This requires a long incisional biopsy; a punch biopsy is not adequate. The procedure itself does not alter prognosis. Expert shave biopsies (tangential excision) may be useful to obtain a larger surface area of a flat lesion without significant morbidity.

Re-excision margins depend on the site of the lesion and its Breslow depth. There should be a clearance width and depth of 1 cm for all invasive tumours and deep to fascia. This may require a flap or graft repair to close the wound. Tissue-sparing Mohs micrographic surgery may be worthwhile for lentigo maligna melanoma, in which clinical margins are frequently unclear.

The current recommendations are:

| Tis | Margin 5mm |

| T1, pT2 | Margin 1cm |

| T3 | Margin 1 to 2 cm |

| T4 | Margin 2 to 3 cm |

About 25% of melanomas 1.5–4mm thick have microscopic lymph node involvement at the time of primary diagnosis, and 60% if > 4mm thick. Elective lymph node dissection is not recommended because of significant morbidity and may not improve survival. However, in cases without palpable regional lymphadenopathy, lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy should be considered (if available locally) for melanomas > 1 to 1.5 mm in thickness.

A sentinel node biopsy procedure (or preoperative and intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy) involves injecting preoperative radionucleotide and dye into the site of the primary lesion at the time of wide excision. A scanner detects the radionucleotide at the regional lymph nodes. At incision, blue dye is detected within the so-called sentinel lymph node, i.e. that on a direct path from the primary lesion. This is excised for frozen section histology. S-100 immunocytochemistry is used to detect occult micrometastases. If positive, the regional lymph node region is cleared. The number of involved nodes is counted.

Melanoma may recur or metastasise locally, in transit to local lymph nodes, in lymph nodes and internally. These areas should be examined at follow-up. Two-thirds of metastases occur within 2 years of removal of the primary lesion.

Melanoma overlying Neglected subungual melanoma Lymph node metastasis Amelanotic metastasis Ulcerated dermal metastasis Disseminated melanoma

In lesions under 1.5 mm in depth and without clinical secondary disease, no specific investigations are warranted. For thicker tumours, or when metastasis has been detected, chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasound are justified for staging.

Treatment of metastatic disease

Survival outcomes

The estimated 10-year survival rates in 1996 according to the South Australian Cancer Registry:

| pTis | Melanoma in situ | 100% |

| pT1 | Melanoma <0.75 mm thick | 97.9% |

| pT2 | Melanoma >0.75 mm<1.5 mm thick | 90.7% |

| pT3a | Melanoma >1.5 mm <3.0 mm thick | 75.4% |

| pT3b | Melanoma >3.0 mm <4.0 mm thick | 55.0% |

| pT4 | Melanoma >4.0 mm thick | 40% |

Prognosis according to the AJCC staging classification (simplified) is shown in the table below.

| Stage 0 | Melanoma in situ |

| Stage 1 (90-95% 5-year survival) | T1a/b, T2a |

| Stage II (45-78% 5-year survival) | T2b, T3a/b, T4a/b |

| Stage III (26-66% 5-year survival) | Involved lymph nodes |

| Stage IV (7.5-11% 5-year survival) | Distant metastases |

Find out if pregnancy or oestrogen use increases the risk of melanoma and/or whether pregnancy worsens prognosis.

Information for patients

See the DermNet bookstore.