Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Dr Jenny Caesar, Dermatology Registrar, Glamorgan House, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK. DermNet Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/Prof. Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. June 2020.

Introduction Demographics Causes Clinical features Complications Diagnosis Differential diagnoses Treatment Outcome

Submit your photo of cutaneous diphtheria

Diphtheria is a bacterial infection caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, and C. ulcerans, gram-positive bacilli. It generally affects the respiratory system and can also affect the skin. Although infection with C. diphtheriae can be prevented by vaccination and is very rare in countries with an immunisation programme, C. ulcerans infection is not prevented by vaccination, and is an emerging zoonotic pathogen.

Cutaneous diphtheria presents as a slow-healing ulcer.

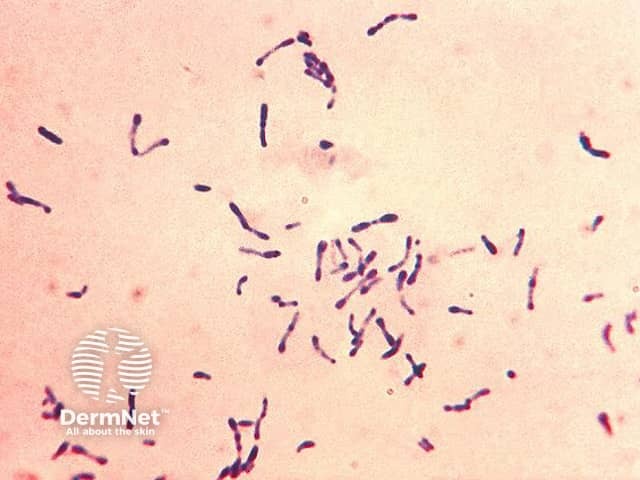

Corynebacterium diphtheriae Gram stain

Cutaneous diphtheria typically occurs in tropical areas where C. diphtheria is endemic, including in:

In developed countries, cutaneous diphtheria most commonly presents in unvaccinated individuals following travel to an endemic area, or has been contracted from domesticated pets or wild animals.

Outbreaks of cutaneous diphtheria have been reported in disadvantaged communities living in overcrowded conditions with poor access to sanitary facilities and healthcare.

Transmission of C. diphtheriae is thought to occur via direct contact with infected skin and contaminated dressings.

Cutaneous diphtheria has also been reported after traditional tattooing.

Cutaneous diphtheria is caused by infection with Corynebacterium diphtheriae and the zoonotic Corynebacterium ulcerans, which is the predominant cause in the UK and Europe.

C. diphtheriae is a gram positive, non-encapsulated bacillus. Both toxigenic and non-toxigenic strains have been implicated in cutaneous infection.

Toxigenic strains of C. diphtheriae cause systemic toxicity.

Respiratory disease due to diphtheria characteristically presents as a sore throat, with cervical lymphadenopathy, and progressive respiratory distress. On examination a thick, grey-coloured membrane coats the pharynx. Concurrent respiratory and skin infection are rare.

Cutaneous diphtheria is typically ulcerative. It begins as a vesicle or pustule which quickly breaks down to form a well-defined superficial ulcer with an overhanging edge. The ulcer is often described as having a punched-out appearance. Ulcers may be solitary or multiple, measuring several millimetres to centimetres in diameter. The hands, feet, and legs are the most common sites involved. The ulcer is initially painful, becoming asymptomatic with time. As the ulcer deepens, a brown-grey adherent membrane or pseudomembrane forms in the base. The surrounding skin is pink to purple in colour and can be swollen with a rolled appearance and possible blisters. Regional lymph nodes may be enlarged.

Cutaneous diphtheria ulcers usually heal spontaneously in 2-3 months to leave depressed scars.

Localised injury to the skin often precedes infection, for example, a graze or insect bite. Cutaneous diphtheria has also been identified after colonisation and infection of an existing skin condition such as dermatitis or scabies.

Cutaneous diphtheria may be challenging to distinguish from skin infection caused by another pathogen, especially given its relative rarity in developed countries.

Unlike respiratory diphtheria, in which there is a slow immune response that may not lead to subsequent immunity, cutaneous diphtheria typically results in a rapid antibody response. This means that individuals with skin infection are unlikely to develop concurrent pharyngeal diphtheria.

Systemic toxicity from cutaneous diphtheria due to toxigenic strains of the bacteria is rare, only occurring in 1–2% of cases.

Possible systemic complications linked to toxigenic diphtheria include:

Infected skin can be a reservoir for respiratory diphtheria in others, particularly in areas where herd immunity is low due to suboptimal immunisation.

The diagnosis of cutaneous diphtheria should be considered for a non-healing ulcer typically after recent travel to an endemic area.

C. diphtheriae or C. ulcerans may be cultured from a bacterial wound swab.

As laboratory processing for diphtheria may not be routine, it is vital that complete clinical information is provided to alert the laboratory to consider culture for atypical organisms.

The differential diagnosis for cutaneous diphtheria includes:

Cutaneous diphtheria infection needs to be identified and treated to prevent spread of disease. Treatment includes:

Cases are not contagious after 48 hours treatment with appropriate antibiotics.

Diphtheria is a notifiable disease in New Zealand and public health advice should be sought. Contact tracing is advised. Nasal, pharyngeal, and skin swabs should be obtained. Contacts may require prophylaxis with erythromycin 500 mg QDS for 7–10 days.

Vaccination is essential to promote herd immunity and to reduce the risk of transmission of C. diphtheriae. In New Zealand, vaccination against diphtheria is part of the National Immunisation Schedule and is given concurrently with tetanus and pertussis and sometimes also with polio, hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenzae type b.

The prognosis for uncomplicated cutaneous diphtheria is good, with most cases responding to oral antibiotics and simple wound care measures.

Mortality is reported at 5–10% in systemic toxigenic diphtheria.

To prevent re-infection, individuals and close contacts should ensure their vaccination status is up to date.