Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Lesions (benign) Diagnosis and testing

Author: A/Prof Patrick Emanuel, Dermatopathologist, Auckland, New Zealand; Harriet Cheng BHB, MBChB, Dermatology Department, Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand, 2013.

Lentigo simplex Labial and genital melanotic macules Solar lentigo Lichen planus-like keratoses Ink-spot lentigo Ephelis (freckle) Nail matrix lentigo Lentiginous naevus Lentiginous dysplastic naevus of the elderly Atypical lentiginous hyperplasia Differential diagnoses

Histologically, the hallmark of the lentigo (plural lentigines) is an increase in basal melanin. In most forms of lentigo, there is a mildly increased number of melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis and variable elongation of the rete ridges.

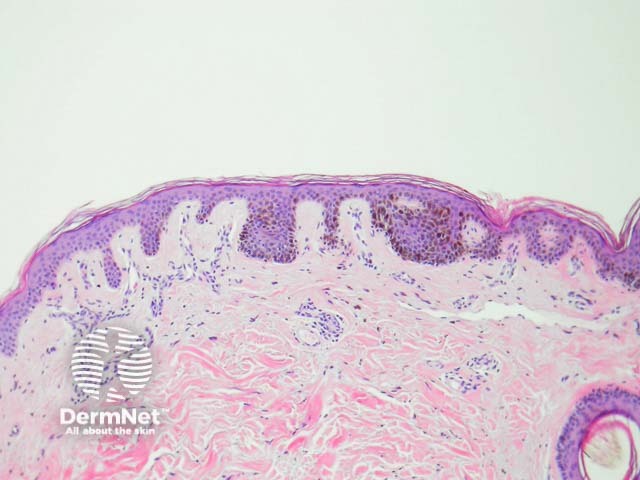

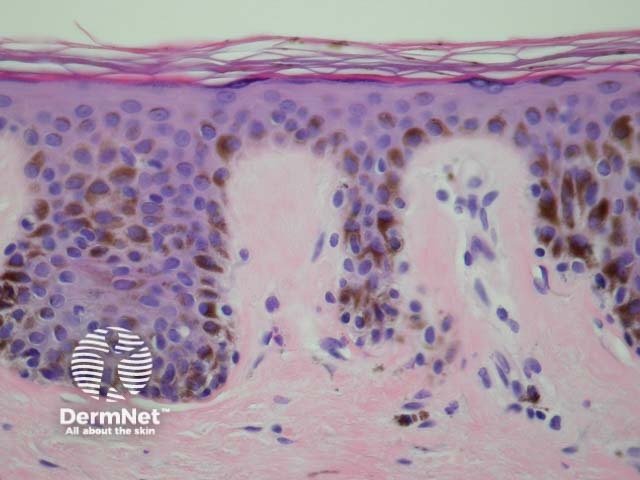

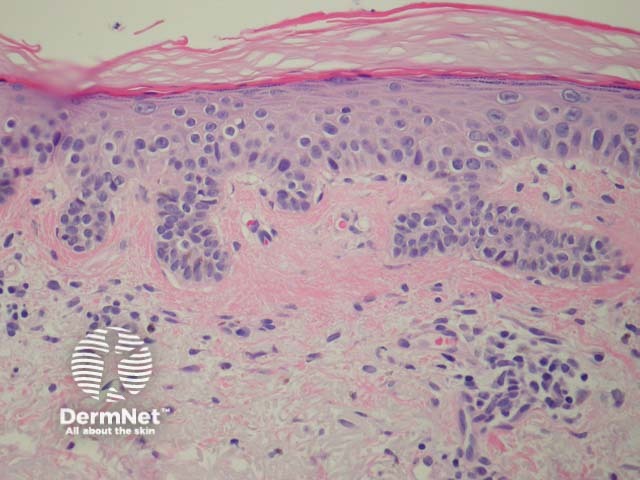

Lentigo simplex is a common lesion and usually appears in childhood. Key features include mild epidermal acanthosis, increased numbers of uniformly dispersed single melanocytes without atypia in the basal layer and variable basal hyperpigmentation (figures 1, 2). Occasionally, there is a sparse papillary lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. If the infiltrate includes numerous melanophages the dermatoscopic presentation may be atypical.

Figure 1

Figure 2

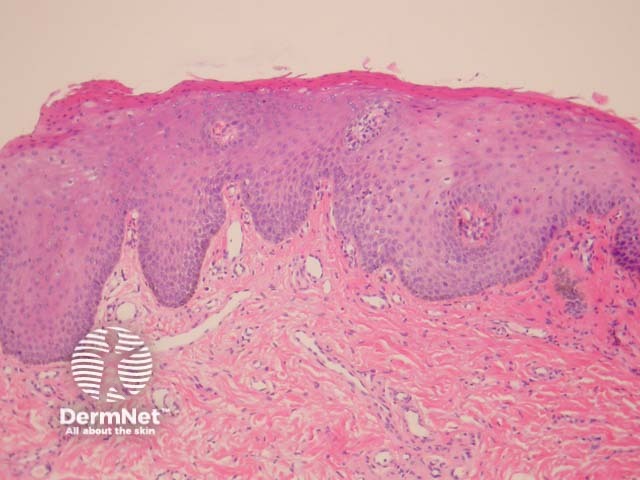

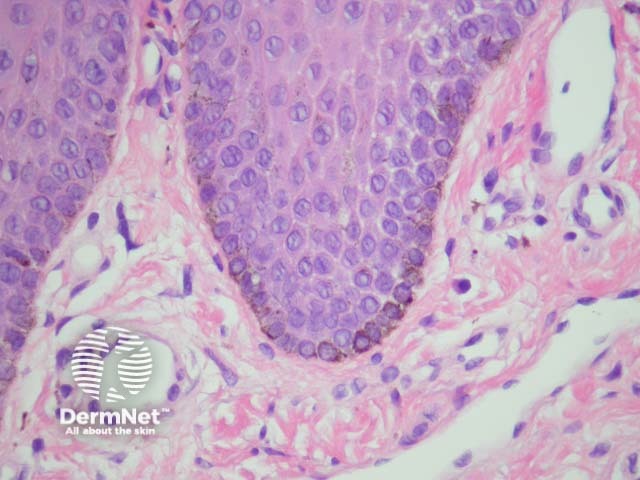

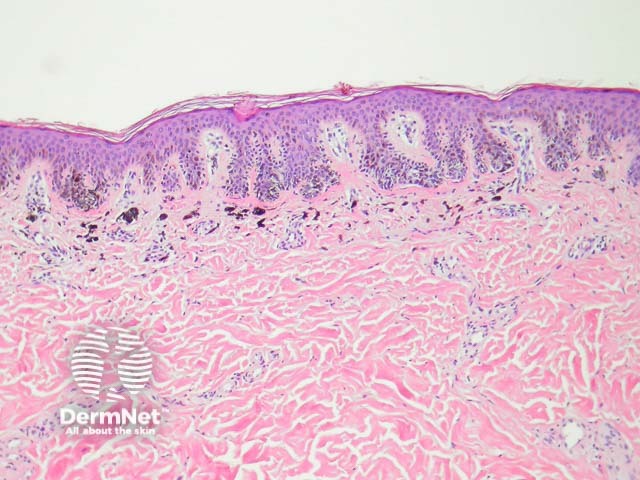

The histopathology of labial melanotic macules (appearing on the lips or oral mucosa) and vulvar and penile melanotic macules are similar to cutaneous lentigo simplex, however acanthosis is less prominent. Dermal melanophages are almost invariably present, and can be a helpful clue to the diagnosis, particularly in subtle oral lesions (figures 3, 4). Differential diagnosis is postinflammatory pigmentation.

Figure 3

Figure 4

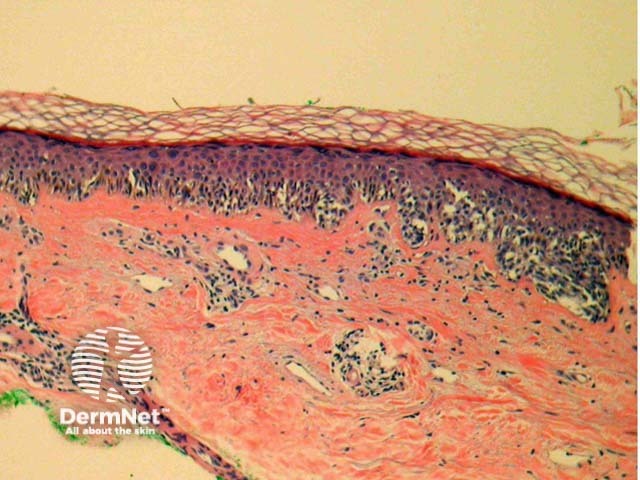

Solar lentigines are benign lesions occurring on sun-exposed skin. Pathogenesis is related to repeated intermittent sun exposure and ultraviolet-induced mutations leading to enhanced melanin production and abnormal pigment retention by keratinocytes.

Histologically, there is a conspicuous bulb-like elongation of rete ridges that form a reticular pattern due to interconnections between adjacent strands. This may be less conspicuous in facial lesions. In some cases there is morphologic overlap with macular seborrhoeic keratoses. Basal layer hyperpigmentation may be marked. There is often a mild increase in the numbers of melanocytes, particularly at the tips of elongated rete ridges. Solar elastosis is usually seen in the dermis (figure 5).

On facial skin, any significant melanocytic hyperplasia developing in a solar lentigo should raise suspicion of an early evolving lentigo maligna – careful search for junctional nesting, adnexal invasion and nuclear atypia is prudent in all of these cases, and caution should be taken in reporting partially sampled lesions.

Figure 5

Solar lentigines quite commonly undergo regression via a lichenoid reaction pattern, which may be difficult to distinguish from lichen planus histopathologically. These lesions are often clinically and dermatoscopically recognisable and are known as ‘lichenoid keratoses’ or ‘lichen planus-like keratoses’. They are very commonly biopsied when mistaken clinically for superficial basal cell carcinoma or an atypical melanocytic lesion with history of change.

Ink-spot lentigines are identified by very dark pigmentation. They appear as irregular black macules often among a number of solar lentigines. Though sometimes clinically alarming, these have a highly characteristic dermatoscopy and histology. They show regions of marked basal hyperpigmentation which may alternate with achromatic skip areas.

Ephelides may easily be overlooked histopathologically. The only finding is a mild basal hypermelanosis.

Nail matrix lentigines present as greyish-brown longitudinal bands in a nail plate (melanonychia). They may be easily overlooked histopathologically. Basal hypermelanosis is seen. Even a mild hyperplasia of melanocytes with a dendritic morphology should raise the possibility of an atypical melanocytic proliferation or melanoma.

An occasional feature of lentigo simplex is isolated junctional nests of melanocytes. A lentiginous naevus (also called naevoid lentigo or ‘jentigo’) has few junctional nests and lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia at the periphery (figure 6). A continuum may exist whereby lentigo simplex can evolve to form junctional then compound and finally intradermal naevi.

Figure 6

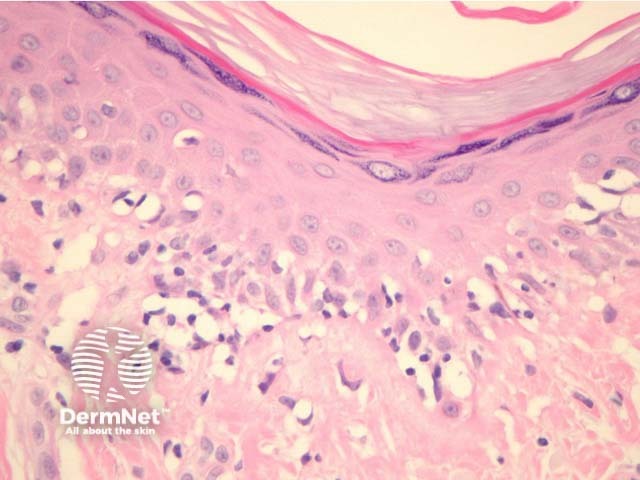

Lentiginous dysplastic or atypical naevus of the elderly is a rather controversial lesion which has probably also been reported as lentiginous melanoma (see below) and Kossard naevus. The slowly evolving radial growth pattern has led many authors to believe it represents a low-grade melanoma. These lesions are far more common in New Zealand than quoted in North American literature and typically present on chronically sun-damaged skin of older adults (usually > 60 years).

On histology there is lentiginous proliferation of single melanocytes in the basal layer, which are a variable density, some areas becoming confluent. Occasional nests form. Melanocytes display mild cytological atypia with hyperchromatic nuclei. Pagetoid spread is often not a prominent feature. Dermal changes include focal fibrosis within the papillary dermis, pigmentary incontinence and lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Interestingly, aggregates of bland melanocytes are frequently present in the superficial dermis (figures 7, 8).

Figure 7

Figure 8

The term ‘atypical lentiginous hyperplasia’ is being increasingly used by pathologists to describe lentiginous hyperplasia where melanocytes display some cytological atypia with minimal nesting of melanocytes and without florid pagetoid spread. It is probably unknowable how many of these are melanoma in situ in a very early stage of evolution. In most cases it is advisable to surgically manage them with 3–5 mm surgical margins to ensure complete removal and/or clinically follow the site.

Lentigines must clinically and histologically be distinguished from melanocytic naevi, melanoma and seborrhoeic keratoses