Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Reactions Diagnosis and testing

Author: Dr Ian Coulson, Consultant Dermatologist, East Lancashire NHS Trust, UK. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. Updated December 2021

Introduction

How it works

Allergen selection

Interpretation

Photopatch tests

Adverse reactions

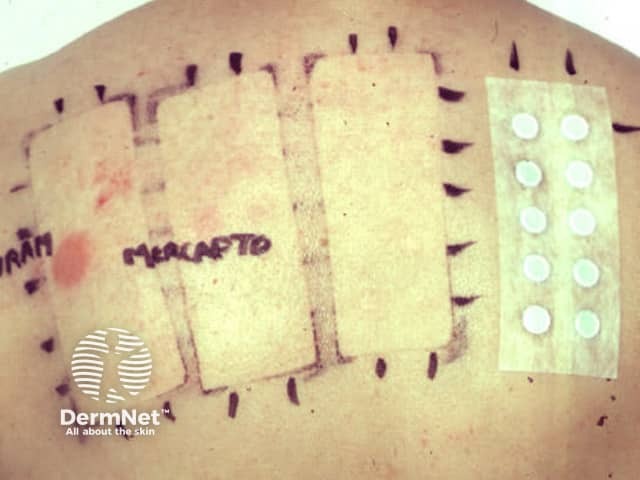

Patch testing is undertaken for the investigation and confirmation of substances that produce allergic contact dermatitis. It involves applying appropriately diluted allergens to the skin, usually on the back for convenience, for 48 hours. The patch tests are then read at 96 hours as reactions usually take 48–96 hours to develop. Positive reactions produce a patch of dermatitis at the application site of the offending allergen, which will appear as a red and possibly raised, vesicular and even blistering area.

Patch test series before application of patch test

Patch test strips in place after application

Patch test removal at 48 hrs with positive reaction to a rubber accelerator

Dermatitis can be thought of as being exogenous (eg, irritants, allergens, and sometimes light) or endogenous. In practice, dermatitis may be of mixed cause. Patch testing is largely of value in determining the cause of allergic contact dermatitis, and is not useful in investigating irritant dermatitis. Patch testing has some limited value in investigating some types of drug allergy, and a specialised type of patch testing is used for investigating photo contact allergy (photopatch testing).

Repeat open application testing can sometimes help identify a suspect item (usually a personal care product) if there is a delay in formal patch testing — the product is applied twice a day to a 5 cm diameter area of forearm skin for 5–10 days. No visible redness or swelling means contact allergy to that product is unlikely. Some highly irritant products cannot safely be repeat open or occluded patch tested, as they may require appropriate dilution.

Patch tests are not the same as skin prick tests, which are used to diagnose hay fever allergy.

A series of allergens are applied, usually to the back, on special tapes fitted with small aluminium discs (Finn chambers) that hold the individual allergens (between 10 and 12). Anywhere between 30 and over a hundred allergens can be applied at a time. Ideally the patch tests are applied when the dermatitis is inactive, but if the back skin is inflamed, the arms or abdominal skin can be used for application. After carefully marking the position of the patch test panels, they are removed at 48 hours, and the skin inspected 48 hours after that.

During patch testing, it is best to:

Antihistamines can be taken as normal as they do not interfere with the type IV hypersensitivity reaction.

There are several thousand potential contact allergens, but some are much more common than others. A baseline series of allergens at least will usually be applied. The composition of the series varies over time and from country to country, as different allergens may become more or less important. The baseline series will pick up about 70% of contact dermatitis.

Additional series of allergens may be applied, according to:

At a pre-patch test consultation, the series of allergens required are selected. This is important so that potential allergens are not missed, and any product dilution arranged.

It is helpful to bring health and safety data sheets and product packaging (which may list individual allergen ingredients). If there is a suspicious product that may be the cause of dermatitis, it is important this is brought along to the doctors appointment. Patch testing may be required and its packaging will contain valuable details of its constituents.

Reactions are graded for each allergen on a spectrum as:

Some allergens are coloured and will temporarily stain the skin (PPD is black, disperse blue is blue, textile resins are a variety of colours. The colour can be removed with an alcohol swab and these are not to be confused with true positive reactions.

+ patch test reaction

Patch test ++ reaction to neomycin

+++ reaction to compositae mix

Irritant reactions can occur in those with atopic eczema, particularly to metals (nickel, chromate and cobalt), perfumes and some rubber accelerators, and are not relevant.

Negative results may mean that the dermatitis is endogenous or irritant in cause, or perhaps the allergen may have been missed (not considered or tested for, or may even be a novel allergen).

Positive reactions are, if possible, then interpreted as being of:

Detailed information sheets can be given for many of the allergens which will guide patients as to where they may find, and therefore avoid, the identified allergen. It is useful to make a note of identified allergens for checking products when shopping. Most countries mandate that allergen constituents appear within or on the packaging or several types of product, particularly personal care items. The print can be very small, and cosmetic manufacturer’s websites usually list constituents, are up to date and easier to read.

Some people will tolerate a product applied to their covered skin, but will react to the product on exposure to light (photocontact dermatitis). This can be investigated by photopatch testing; this may be relevant to some fragrances, antiseptics, plant allergens, and sunscreen reactions.

Two identical panels of photopatch allergens are applied to the back, and at 48 hours only one of the panels is exposed to ultraviolet light. The patches are read at 96 hrs. Photocontact dermatitis is diagnosed when only the exposed allergen produces a positive reaction.

Positive reactions produce small itchy patches of eczema. At the end of the testing, this can be treated with a topical steroid.

Other adverse reactions include:

Black skin staining due to the hair dye allergen PPD

"Angry back" – multiple positive reactions due to eczema being too active