Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Vaccines against human papillomavirus — extra information

Vaccines against human papillomavirus

Author: Sonam Vadera, Medical Student, University College London, London, United Kingdom. DermNet New Zealand Editor in Chief: Hon A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell/Maria McGivern. October 2017. Updated February 2021.

Introduction

Introduction - sexually acquired HPV

HPV and cancer

Available vaccines

How it works

Benefits

Side effects and risks

Demographics

Contraindications

Should cervical screening continue?

What are vaccines against human papillomavirus?

Vaccines have been developed to immunise against sexually acquired human papillomavirus, particularly those that cause cervical and other mucosal squamous cell carcinomas. Injected HPV vaccines are offered in national immunisation programmes in at least 99 countries and territories, with at least 11 of those vaccinating both boys and girls.

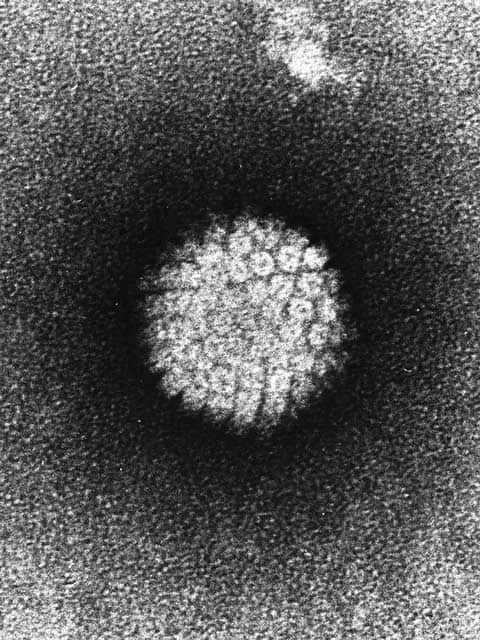

Human papillomavirus

Papillomavirus

What is sexually acquired human papillomavirus?

Some types of human papillomavirus (HPV) are classified as sexually transmitted infections (STIs). These HPV types infect the skin and mucosa of the anogenital tract and upper respiratory tract. Sometimes these HPV infections have been acquired during birth (vertical transmission from mother to baby). In many individuals, the virus does not cause symptoms and infection may resolve by itself or become latent.

Persistence of these HPV infections can lead to:

- Anogenital wart: most common sexually-acquired HPV-associated lesion and is usually due to low-risk types HPV 6 and 11.

- Precancerous squamous intraepithelial lesions, such as vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN), cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), and anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN).

- Invasive cancers, such as cervical cancer and anal and anal canal cancer, and is associated with some cases of vulval squamous cell carcinoma, and oropharyngeal cancers including oral cancer.

Of the over 200 HPV types, at least 14 high-risk types of HPV are associated with precancerous squamous intraepithelial lesions and invasive cancer. HPV causes nearly all cervical cancers, with HPV 16 and HPV 18 being responsible for 70% of these cases. High-risk HPV types also cause up to 99% of anal squamous cell carcinomas but are found less commonly in vulval, vaginal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers.

HPV-related cancer is more common in immunosuppressed patients, such as associated with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, or drug-induced immunosuppression.

Anogenital lesions associated with human papillomavirus

Scrotal wart

Vulval high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

Penile squamous cell carcinoma

How does human papillomavirus cause cancer?

Cervical cancer

HPV infects basal keratinocytes in the cervix through small breaks between the epithelial cells. Following exposure to high-risk types, the immune system sometimes clears the virus or infection can become latent.

In some women, infection persists and overproduction of the early viral proteins E6 and E7 leads to unregulated cellular proliferation resulting in the cellular dysplasia called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

The degree of cervical dysplasia is graded from CIN1 (minimal dysplasia) through to CIN3 (full-thickness dysplasia). These cellular changes may resolve spontaneously or progress to invasive cancer. The risk of cancer correlates with the CIN grade. Those who are immunosuppressed or who smoke are at high risk of progressing to cancer.

Other cancers

Similar processes occur less frequently in other mucosal sites in the anogenital area and upper respiratory tract following exposure to oncogenic HPV types.

The course of HPV infection in these sites is similar in its progression to cervical cancer. For example, squamous cells of the anal epithelium can undergo dysplasia, leading to anal intraepithelial neoplasia, which can progress to anal cancer. Such precancerous and cancerous changes can also occur in the vulva, vagina, penis, and oropharynx, and similar grading systems are used for the site-specific squamous intraepithelial neoplasia.

What vaccines are available to protect against human papillomavirus infection?

There are currently three vaccines available to protect against HPV infection.

- Cervarix® — a bivalent vaccine against HPV 16 and 18, the two HPV types most commonly associated with cervical cancer

- Gardasil® — there are two forms of the Gardasil vaccine; both protect against cervical cancer and genital warts:

- Gardasil® is a quadrivalent vaccine protecting against four HPV types; HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18

- Gardasil®9 is a nine-valent (nonavalent) vaccine protecting against nine types of HPV; low-risk HPV types 6 and 11, high risk HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

How do vaccines work to prevent human papillomavirus infection?

Vaccines against HPV consist of virus-like particles (VLPs) derived from HPV surface proteins. These are produced by recombinant DNA technology. VLPs are empty protein shells without a viral genome and do not infect human cells.

VLPs prime the immune system by eliciting an antibody response against the viral surface proteins. Subsequent exposure to a HPV type covered by the vaccination is neutralised by the specific antibodies before the virus can cause infection.

To be effective, the vaccines need to be given before HPV infection has occurred, and in most people, this is before their first sexual encounter. Vaccination does not help those who have already been infected with a HPV type contained in the vaccines.

What are the benefits of vaccination against human papillomavirus?

The vaccines are over 99% effective at preventing CIN and cervical cancer associated with HPV 16 and 18 infection, with protection lasting at least 10 years. Both forms of the Gardasil® vaccine also prevent disease resulting from the low-risk HPV types 6 and 11, and the newer nine-valent Gardasil®9 additionally covers high-risk HPV types 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

The vaccines are also effective at preventing HPV-associated in-situ and invasive cancers in other anogenital sites and oropharynx of both sexes. The nine-valent Gardasil®9 has 100% efficacy against HPV-related vaginal and vulval cancers, and 75% efficacy against anal cancers.

Both forms of Gardasil®9 are 99% effective at protecting against genital warts caused by HPV 6 and 11. In New Zealand, Gardasil®9 is also funded for treatment of some patients with juvenile-onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis.

A degree of protection against the HPV types not included in the vaccines has been found. Efficacy has been reported against HPV types 31, 33, 45 and 51 in studies following vaccination against only HPV types 16 and 18. In addition, a ten year followup of women following the bivalent HPV16/18 vaccine showed a reduction in CIN3 irrespective of HPV type, but was not effective for women who already had HPV 16 at the time of vaccination.

Herd immunity has been documented in countries vaccinating against HPV 6 and 11 only in girls, with a decrease in genital warts also observed in males. However a similar reduction has not been seen in men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM).

What are the possible side effects and risks of human papillomavirus vaccination?

Common side effects of vaccination include:

- Swelling, pain, and redness at the injection site for a few days

- Mild muscle aches, fatigue, fever, and headaches for hours to days.

Anaphylaxis is a rare complication encountered by very few individuals (1.7 cases per million doses).

Who gets the human papillomavirus vaccine?

Free vaccination schedules vary from country to country, and from year to year. The vaccine is also available privately.

This information is current from February 2021.

United States

HPV vaccination is recommended for all boys and girls aged 11 or 12 years old. The recommended schedule is two doses 6–12 months apart. Females up to the age of 26 years and males up to age 21 may have catch-up immunisations recommended if they have not yet been vaccinated; in such cases, three doses are required. Men who have sex with men and immunocompromised males have vaccination recommended through to age 26. The nine-valent Gardasil®9 vaccine is used and is available on a private basis.

United Kingdom

All girls in the UK are invited for free vaccination with the quadrivalent Gardasil® vaccine. A two-dose schedule is required for girls under the age of 15 years. The first dose is given between the ages of 12 and 14 years, with a second dose given 6–24 months later. Girls over the age of 15 require three doses.

As of August 2019, the vaccination programme in the UK covers boys, as well as girls, on the usual schedule. Men who have sex with men have recently been added to the immunisation programme in an attempt to protect against anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers.

Immunosuppressed individuals or those with HIV may also be recommended vaccination. Specialist advice should be sought.

Australia

Boys and girls aged 9-14 years are offered free vaccination, usually as part of the school vaccination program at age 12-13 years; the nine-valent Gardasil®9 vaccine is given as two separate doses 6 months apart. Three doses are required for those 15 years and older (at 0, 2 and 6 months). Vaccination of boys began in 2013. There is a free catch-up programme available for boys aged 14–15 years. Two doses are funded by the National Immunisation Program (NIP). For all others, the vaccine is available privately at a separate cost unless there are specific medical risk factors.

New Zealand

All girls and boys aged 11–12 years in New Zealand are invited for a vaccination with nine-valent Gardasil®9. The vaccine is funded for children and young adults aged 9–26 years. Two doses are required up to the age of 14 years; in individuals over 15 years old who are receiving catch-up vaccinations, three doses are required.

What are the contraindications to vaccination against human papillomavirus?

Vaccination is not recommended against HPV in the following circumstances:

- Where there is a history of previous anaphylaxis to the vaccine components — this includes an allergy to yeast products (a component of the vaccine)

- Pregnancy — vaccination against HPV is avoided in pregnancy, although accidental vaccination during pregnancy has not been reported to result in adverse effects for the mother or baby.

Should cervical screening continue?

Screening programmes worldwide aim to detect CIN and cervical cancer at the earliest possible stage using cytology and/or HPV DNA testing and typing. Early detection of CIN enables treatment and prevents the progression to cancer.

Cervical screening programmes for women differ worldwide.

- US: Cervical screening consists of cytology screening every 3 years at ages 21–29, followed by cytology screening with HPV testing every 5 years at ages 30–65.

- UK: Cervical screening consists of cytology, potentially followed by HPV testing depending on findings, every 3 years at ages 25–49, and subsequently, every 5 years for women aged 50–64.

- Australia: Cervical screening consists of HPV testing every 5 years in women aged 25–74 years.

- New Zealand: Cervical screening consists of cytology testing every 3 years in women aged 20–69.

Screening is still recommended in vaccinated women, but this is under review.

Other screening programmes

Male and female patients with immunosuppression (eg, those with HIV infection or on immunosuppressive drugs) are recommended to undergo regular anal cytological or HPV screening.

Bibliography

- Arbyn M, Xu L, Simoens C, Martin-Hirsch PP. Prophylactic vaccination against human papillomaviruses to prevent cervical cancer and its precursors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD009069. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009069.pub3. PubMed Central

- Bergman H, Buckley BS, Villanueva G, et al. Comparison of different human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine types and dose schedules for prevention of HPV-related disease in females and males. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019(11):CD013479. PubMed Central doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013479.

- Garland SM, Kjaer SK, Muñoz N, et al. Impact and effectiveness of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: a systematic review of 10 years of real-world experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):519–27. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw354. PubMed Central

- Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen OE, et al. A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):711–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1405044. PubMed

- Lehtinen M, Lagheden C, Luostarinen T, et al. Ten-year follow-up of human papillomavirus vaccine efficacy against the most stringent cervical neoplasia end-point-registry-based follow-up of three cohorts from randomized trials. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e015867. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015867. PubMed Central

- Patel C, Brotherton JM, Pillsbury A, et al. The impact of 10 years of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Australia: what additional disease burden will a nonavalent vaccine prevent?. Euro Surveill. 2018;23(41):1700737. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.41.1700737. PubMed Central

- Quattrone F, Canale A, Filippetti E, Tulipani A, Porretta A, Lopalco PL. Safety of HPV vaccines in the age of nonavalent vaccination. Minerva Pediatr. 2018;70(1):59–66. doi:10.23736/S0026-4946.17.05147-7. PubMed

- Wheeler CM, Castellsagué X, Garland SM, et al. Cross-protective efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by non-vaccine oncogenic HPV types: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2012 Jan;13(1):e1]. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(1):100–10. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70287-X. PubMed

- Urman CO, Gottlieb AB. New viral vaccines for dermatologic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(3):361-70. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.07.051. PubMed

- Gardasil 9 – The Next Generation Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine. Prescriber Update. Medsafe New Zealand, December 2016.

On DermNet

- Laboratory tests for viral infections

- Viral wart

- Sexually acquired human papillomavirus

- Non-sexually acquired human papillomavirus infection

- Genital warts images

- Squamous intraepithelial lesions

- Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

- Penile intraepithelial neoplasia

- Anal cancer and anal canal cancer

- Carcinoma in situ of oral activity

- Vulval cancer

- Oral cancer

- Bowenoid papulosis

Other websites

- HPV immunisation programme — Ministry of Health NZ

- The Immunisation Advisory Centre (IMAC) — University of Auckland NZ

- Immunisation — GOV.UK

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) — Australia Department of Health

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) — US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- HPV vaccine — MedlinePlus

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine — UpToDate patient information

- HPV vaccines — WebMD

- HPV vaccines — American Cancer Society

- Nature milestones in vaccines — Nature Research animation (how vaccines work, history of vaccines)