Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Dr Varitsara Mangkorntongsakul, Junior Medical Officer, Central Coast Local Health District, Gosford/Hamlyn Terrace, NSW, Australia. DermNet Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell/Maria McGivern. August 2018.

Introduction Demographics Causes Clinical features Diagnosis Treatment Outcome

Winter itch, also known as pruritus hiemalis, is a type of subclinical dermatitis, that affects individuals during cold weather.

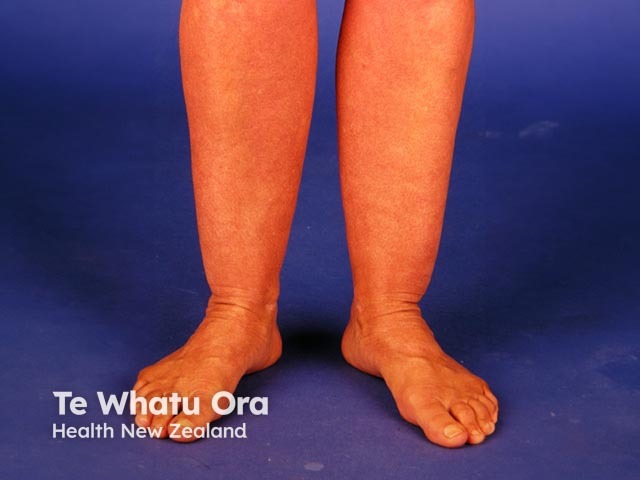

Apparently normal skin

Excoriations

Dermatitis

Winter itch can affect the healthy population of all ages, but has a higher prevalence in older people with dry skin.

The exact cause of winter itch is unknown. Factors associated with winter itch include:

Similar symptoms have also been reported in patients exposed to refrigerated air conditioning during the summer months. Winter itch is not influenced by frequency of bathing or by the temperature of the bath water.

Winter itch does not cause a primary visible rash. The affected skin generally appears healthy, but usually slightly dry.

Secondary lesions arise as a consequence of chronic scratching.

Winter itch can be associated and confused with other diseases that cause itchiness, particularly dermatitis (where there is a visible rash), and pruritus associated with systemic diseases (which tends to be generalised).

Detailed history taking and careful examination are important to rule out other potential causes of pruritus.

Treatment is mainly to provide symptomatic relief and prevent scratching.

Systemic agents are not indicated for winter itch, but oral antihistamines and systemic corticosteroids are sometimes prescribed as a clinical trial.

Winter itch normally resolves after the winter months.