Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Barrier function in atopic dermatitis — extra information

Barrier function in atopic dermatitis

Author: Dr Claire Felmingham, Resident Medical Officer, Rapid Creek, Australia; A/Prof Rosemary Nixon, Occupational Dermatology Research and Education Centre, Skin and Cancer Foundation Inc., Melbourne, Australia. DermNet Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. October 2018.

Introduction Causes Normal skin barrier function Skin barrier function and atopic dermatitis treatment

What is atopic dermatitis?

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic, itchy skin condition that is associated with dry skin. It typically begins in infancy or childhood and is often associated with other atopic conditions, such as asthma and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (hay fever) [1].

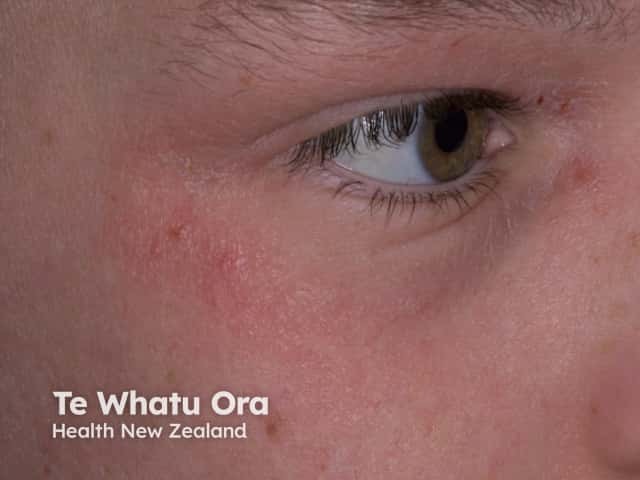

Atopic eczema

Atopic eczema

Atopic hand eczema

What causes atopic dermatitis?

The causes of atopic dermatitis are incompletely understood. The underlying cause of atopic dermatitis is thought to be a result of a weakened skin barrier and a predisposition towards allergic inflammation [2]. Environmental triggers provoke an allergic reaction, which exacerbates the symptoms of atopic dermatitis.

The immunological disturbance arises from T lymphocytes, specifically T helper (Th) type 2 (Th2) cells in the acute phase, and Th1, Th17, and Th22 cells in chronic lesions. Th2 cells produce interleukin (IL)-4 and -13 (IL-13), which upregulate the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) [3].

One theory of the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis is the 'inside-outside theory', where the primary issue is thought to be with the immune system, and the skin barrier becomes dysfunctional secondary to the IgE sensitisation [4].

Another theory is the 'outside-inside theory', where the original defect is thought to be in the skin barrier, leading to increased allergen exposure and subsequent IgE sensitisation [4].

How does the skin barrier normally function?

The skin barrier provides protection from external threats such as pathogens, chemicals, irritants, and allergens, which might cause an immune response if permitted to pass through to the deeper epidermal or dermal layers of the skin [see Structure of normal skin].

The skin barrier also protects the body from epidermal water loss, and skin barrier function can be measured by the rate of transepidermal water loss. Increased transepidermal water loss corresponds with increased skin permeability. Skin barrier function can sometimes also be measured by surface pH, the permeability of tracer compounds, and stratum corneum cohesion and hydration [2]. [see Skin barrier function]

Stratum corneum

The stratum corneum is the uppermost layer of the epidermis. The stratum corneum is comprised of a highly organised intercellular lipid matrix, and corneocytes (flattened cells without nuclei that are filled with keratin filaments); this is often referred to as the ‘brick and mortar’ of the skin, with corneocytes representing the bricks and the lipids representing the mortar [2].

There is altered stratum corneum homeostasis in both the lesional and non-lesional skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. This leads to increased water loss and the increased penetration of allergens [1].

In atopic dermatitis, the structure and composition of both the corneocytes and the intercellular lipid matrix of the stratum corneum can be affected in the following ways:

- Loss or reduced function of filaggrin protein (FLG)

- Increased serine protease activity

- Impaired lipid processing [1].

Filaggrin protein

FLG is important for the structural integrity of the stratum corneum. FLG aggregates keratin filaments inside corneocytes and then helps to form a cornified cell envelope surrounding the corneocytes. The degradation products of FLG further contribute to the water-holding capacity and acidic pH of the stratum corneum. Maintaining the acidic pH is important to regulate the enzyme activity that leads to desquamation, lipid synthesis, and inflammation [2,5].

A loss-of-function mutation in the FLG gene is the strongest genetic risk factor for atopic dermatitis. FLG mutations are associated with an earlier onset of atopic dermatitis, greater disease severity, and persistence of disease. Approximately 50% of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis cases can be attributed to FLG mutations [5].

Serine protease activity and pH

The activity of the serine proteases, such as kallikrein (KLK) 5 and seven is regulated by the pH of the stratum corneum. KLK5 and KLK7 cleave the extracellular corneodesmosomal proteins that link the corneocytes together. Their increased activity leads to decreased corneocyte adhesion and desquamation [6].

Normal skin pH is acidic and restricts the activity of these proteases, which are more active in alkaline environments. In atopic dermatitis, the pH of the skin is elevated, and subsequently so is the serine protease activity [7].

Lipid matrix function

The stratum corneum lipid matrix is composed of three types of lipids — cholesterol, free fatty acids, and ceramides. These form a highly ordered structure of densely packed lipid layers. This intercellular lipid matrix is the main pathway for substances travelling across the skin barrier [2].

In atopic dermatitis, there is a reduction in total lipids, significant deficits of certain types of lipids, and changes in lipid composition. In combination, this leads to the impaired skin barrier function and increased permeability of the stratum corneum [2].

The immune system and skin barrier function

A defect in the skin barrier can facilitate the transport of allergens or haptens (molecules that only elicit an allergic reaction when bound to a protein) into the skin, inducing the release of proinflammatory cytokines causing inflammation of the skin [2].

At the same time, the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13, and the Th2 cytokine IL-22 downregulate the expression of FLG, causing further damage to the skin barrier [2,8].

Skin microbiome and skin barrier function

The cutaneous microbiome is the pathogenic and commensal bacteria, fungi, and viruses that are resident on our skin and help maintain epidermal homeostasis [1].

More than 90% of patients with atopic dermatitis have skin colonized with Staphylococcus aureus [1].

When the stratum corneum is structurally competent, with an acidic pH, and a well-organised lipid matrix, it prevents colonisation with pathogens such as S. aureus, a bacterium that can detrimentally affect the barrier function. S. aureus surface proteins reduce free fatty acid production in the epidermis, leading to increased skin permeability. In patients with atopic dermatitis, S. aureus exotoxins with super-antigenic properties stimulate the production of IgE and cause pruritus. Subsequent excoriations create further defects in the skin barrier [4].

How does the understanding of skin barrier function affect atopic dermatitis treatment?

The understanding that skin barrier dysfunction drives disease activity in atopic dermatitis has resulted in increased interest and emphasis on treatments that improve barrier function.

Moisturisers are the main treatment for atopic dermatitis. Moisturisers that improve barrier function (barrier cream) have been shown to reduce relapse rates in atopic dermatitis with regular use [9].

Restoring skin barrier function may proactively prevent atopic dermatitis from developing or progressing, as has been shown in randomised control trials of neonates at risk of atopic dermatitis treated with a daily moisturiser [10,11].

Moisturiser ingredients that are helpful in atopic dermatitis include [2,12]:

- Physiological lipids (eg, ceramides, cholesterol) — these restore the composition of lipid bilayers in the stratum corneum and reduce skin permeability

- Physiological humectants (urea, glycerol) that do not participate in the metabolic process of the skin, but prevent excessive water loss and keep the stratum corneum hydrated

- Anti-itching agents (eg, glycerol) that block the release of histamine and allow the restoration of the stratum corneum to begin

- Dexpanthenol — this stimulates lipid synthesis and epidermal differentiation

- Occlusive agents (eg, petrolatum) that reduce water evaporation

- Emollients that soften the skin (eg, sorbolene and glycerine cream).

Bathing with water can remove irritants, allergens, and squama (scales) in atopic dermatitis, allowing for repair of the skin barrier. The application of moisturiser soon after bathing is recommended. Non-soap cleansers, which are low in pH and hypoallergenic, are recommended as soap substitutes, as they cause less disruption to the stratum corneum structure and acid mantle [12]. Use of the 'soak and smear' technique (soaking the affected area in water before smearing it in the ointment) increases the effectiveness of topical medicines. The application of topical corticosteroids to wet skin, immediately after bathing, traps water in the stratum corneum and increases the amount of medication delivered by 10–100 times [13].

Bleach baths have proven helpful in decreasing clinical severity of atopic dermatitis, as a result of their antibacterial, antifungal and anti-inflammatory properties [14]. While sodium hypochlorite (bleach) is typically alkaline (pH 11–13), it produces hypochlorous acid (pH 2–7.5) when dissolved in water [15]. It is possible that this acidity helps maintain normal skin barrier function, in addition to acting as an antiseptic.

Other treatments sometimes required in atopic dermatitis include other topical anti-inflammatory treatments, such as:

- Topical calcineurin inhibitors

- Wet wraps

- Antibiotics for secondary infections

- Oral antihistamines for symptom relief.

In cases of severe atopic dermatitis, recommended treatments include:

- Phototherapy

- Oral corticosteroids

- Nonsteroidal immunomodulators or immune suppressants

- Novel biological agents led by dupilumab [16].

References

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology [2 volumes], 4th edn. London: Elsevier, 2017.

- Agner T. Skin barrier function. New York: Karger, 2016. (Current problems in dermatology; vol 49.)

- Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1483–94. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra074081. PubMed

- Elias PM, Schmuth M. Abnormal skin barrier in the etiopathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 9: 437–46. DOI: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32832e7d36. PubMed

- McAleer MA, Irvine AD. The multifunctional role of filaggrin in allergic skin disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131: 280–91. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.668. PubMed

- Elias PM, Hatano Y, Williams ML. Basis for the barrier abnormality in atopic dermatitis: outside-inside-outside pathogenic mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 121: 1337–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.022. PubMed Central

- Hachem JP, Crumrine D, Fluhr J, Brown BE, Feingold KR, Elias PM. pH directly regulates epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis, and stratum corneum integrity/cohesion. J Invest Dermatol 2003; 121: 345–53. DOI: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12365.x. PubMed

- Howell MD, Kim BE, Gao P, et al. Cytokine modulation of atopic dermatitis filaggrin skin expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.012. PubMed

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Christensen R, Lavrijsen A, Arents BWM. Emollients and moisturisers for eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 2: CD012119. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012119.pub2. PubMed

- Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, et al. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134: 818–23. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.005. PubMed

- Horimukai K, Morita K, Narita M, et al. Application of moisturizer to neonates prevents development of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134: 824-30. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.060. PubMed

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis, section 2: management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 116–32. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.023. PubMed

- Assarian Z, O’Brien TJ, Nixon R. Soak and smear: an effective treatment for eczematous dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol 2015; 56: 215–7. DOI: 10.1111/ajd.12300. PubMed

- Huang JT, Abrams M, Tlougan B, Rademaker A, Paller AS. Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in atopic dermatitis decreases disease severity. Pediatrics 2009; 123: e808–14. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-2217. PubMed

- Barnes TM, Greive KA. Use of bleach baths for the treatment of infected atopic eczema. Australas J Dermatol 2013; 54: 251–58. DOI: 10.1111/ajd.12015. PubMed

- Stanway A, Oakley A. Treatment of atopic dermatitis. DermNet. Updated July 2016. Available at: www.dermnetnz.org/topics/treatment-of-atopic-dermatitis/ (accessed 6 October 2018).

On DermNet

- Atopic dermatitis

- Atopy

- Treatment of atopic dermatitis

- Causes of atopic dermatitis

- Complications of atopic dermatitis

- Barrier cream

- Emollients and moisturisers

- Microorganisms found on the skin

- Skin barrier function

Other websites

- Atopic dermatitis — Medline Plus

- Atopic dermatitis clinical guideline — American Academy of Dermatology

- Atopic eczema — British Association of Dermatologists (patient information leaflet)