Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Authors: Dr Claudia Hadlow, Medical Officer, John Hunter Hospital, Newcastle, NSW, Australia; Dr Matthew James Verheyden, Medical Officer, Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Dr Paul Chee, Consultant Dermatologist and Director of Dermatology at the John Hunter Hospital and the Royal Newcastle Centre, NSW, Australia. DermNet Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. July 2020. DermNet Update January 2021.

Introduction Demographics Causes Clinical features Complications Diagnosis Differential diagnoses Treatment Outcome

Submit your photo of Cockayne syndrome

Cockayne syndrome is a rare genetic multisystem degenerative disorder presenting with microcephaly, growth failure, photosensitivity, and features of premature ageing.

Cockayne syndrome is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder that affects all races and both sexes equally. It has a worldwide prevalence of approximately 2.5 cases per million, and an incidence of 1 in 250,000 live births.

Cockayne syndrome results from mutations in excision repair cross complementation (ERCC) genes. There is considerable genetic heterogeneity. It has been classified as CSA and CSB based on the affected gene, ERCC8 or ERCC6 respectively. CSB due to ERCC6 mutations accounts for 80% of cases of Cockayne syndrome. Xeroderma pigmentosum-Cockayne syndrome overlap (XP/CS) complex is a distinct genotype/phenotype with mutations in other ERCC genes (ERCC2, ERCC3, XPD).

Mutations in ERCC genes can cause defective DNA repair following UV radiation exposure. However, the pathogenesis of Cockayne syndrome is more complex than this, as changes can be seen in the fetus and at birth before there has been UV exposure, and typically involves the nervous system in cells never exposed to UV. Clinically, Cockayne syndrome resembles mitochondrial diseases.

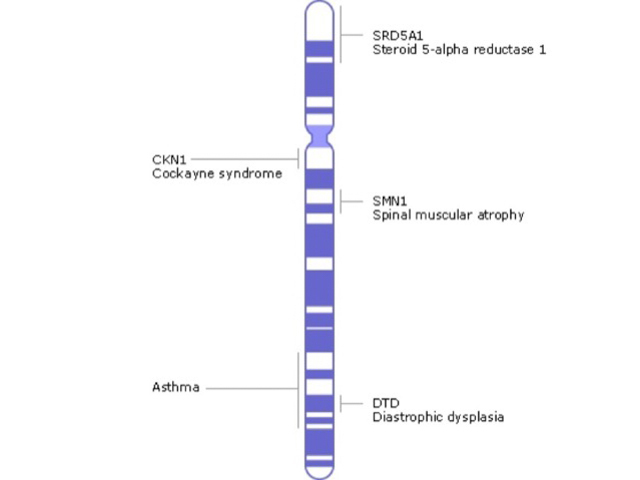

Genetics of Cockayne syndrome

Cockayne syndrome is characterised by microcephaly and failure to grow after birth, in association with other clinical signs. It is classified into three types based on the age of presentation and clinical features, but this does not necessarily correlate with the genetic classification.

There is however considerable phenotypic variability even between affected siblings with the same genotype, and there is a continuous spectrum of clinical features.

Complications resulting from Cockayne syndrome can include the following:

Cockayne syndrome should be suspected in a child with postnatal failure to thrive, microcephaly, and two of the other starred (*) clinical findings.

Diagnosis is confirmed on genetic testing and the demonstration of mutations in the ERCC genes. This can direct parental genetic testing and prenatal diagnosis in subsequent pregnancies.

CT and MRI scans may demonstrate a variety of neuropathologies, including severe cerebral white matter atrophy leading to microcephaly, cerebellar atrophy, basal ganglia calcification, and patchy demyelination (‘tigroid leukodystrophy’).

There is no cure for Cockayne syndrome. Treatment is supportive and directed at preventing and managing complications.

Regular surveillance is recommended for the development of complications, including:

Genetic counselling may be recommended for family members.

Cockayne syndrome is associated with reduced life expectancy with a mean age at death of 12 years: CS-1, 16 years; CS-2, 5 years; CS-3, above 30 years. The most common cause of death is respiratory complications such as pneumonia.