Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Dr Bethany F Ferris, Foundation Year 2 Doctor, Noble's Hospital, Braddan, Isle of Man, UK. DermNet Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell/Maria McGivern. February 2019.

Introduction Peanut allergens Demographics Causes Clinical features Complications Diagnosis Differential diagnoses Treatment Outcome

Peanut allergy is an adverse immune response to a peanut allergen. Reactions include:

Peanut allergy is the most common cause of food-related anaphylaxis [3].

The peanut (Arachis hypogaea) belongs to the legume family and is distinct from the tree nut family.

There are 11 peanut allergens (Ara h 1 to Ara h 11); these allergens are seed storage proteins and biological reserves that enable the peanut seed to grow into a plant.

In the United Kingdom, the prevalence of peanut allergy is reported to be in 0.2–2.5% in children and in 0.3–0.5% in adults [4,5]. A rise in the prevalence was reported in the United States, with 1.4% of children having a peanut allergy in 2008 compared to 0.4% in 1997 [6].

There is a greater risk of peanut allergy in children who have:

Having a peanut allergy results in a low risk of allergy to another legume (eg, peas, beans, lentils, and soybeans) with the exception of lupin. However, one-third of those with a peanut allergy will have a concurrent reaction to a tree nut (eg, walnut, almond, brazil nut, and coconut) [7].

Peanut allergy is more prevalent in the Western world than in China, possibly due to the greater consumption of roasted peanuts rather than raw peanuts [8].

The Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study found that infants at risk of a peanut allergy who have eczema or an egg allergy were less likely to develop a peanut allergy if they had early and sustained consumption of peanuts [9].

Non-allergic mothers are now encouraged to eat potentially allergenic foods such as peanuts regularly during pregnancy and not to delay introducing their babies to them [10].

The cause of peanut allergy is not fully understood.

To develop a peanut allergy, the individual must be exposed to one of the peanut allergens via a gastrointestinal, cutaneous, or respiratory route.

Peanut allergy results in urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis within 30 minutes of exposure to a peanut allergen [1]. It may also cause a late-phase allergic reaction.

Anaphylaxis causes dyspnoea (breathlessness) and wheeze (due to bronchospasm and laryngeal oedema), tachycardia, hypotension, dizziness, and loss of consciousness. Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening clinical emergency [1].

A late-phase allergic reaction can develop 2–6 hours after the initial exposure to the allergen and peaks at around 6–9 hours. This is due to the recruitment of leukocytes and antigen-specific T cells. The late-phase reaction results in erythema and oedema, sneezing, itching, and coughing. It usually fully resolves in 1–2 days [12,13].

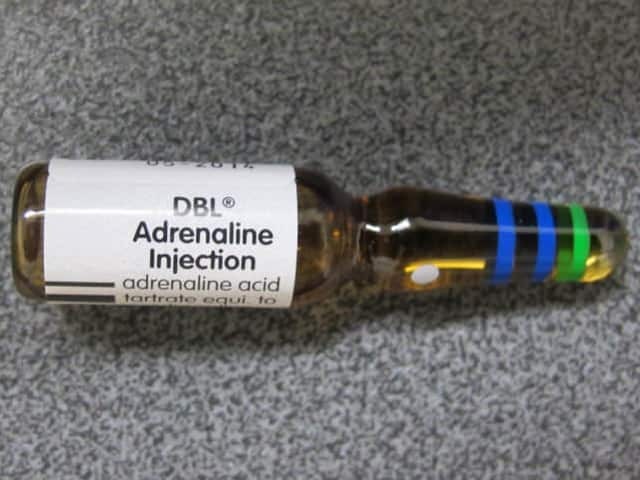

Anaphylaxis can be fatal if not promptly recognised and treated with adrenaline, a bronchodilator, and antihistamines.

Children with asthma have higher mortality from peanut-induced anaphylaxis than non-asthmatic children [14].

Peanut allergy is principally a clinical diagnosis based on the rapid development of allergic symptoms and signs after eating a peanut.

Skin prick testing and serum specific IgE tests are used to identify sensitisation and to confirm the diagnosis [4].

Skin prick testing involves placing a drop of peanut allergen on the skin, then pricking the skin to see if a weal is produced within 15 minutes. The British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) states that a weal ≥ 8 mm in size is highly predictive of peanut allergy. Skin prick testing must be performed in a specialist centre with emergency equipment available in case of anaphylaxis [4].

Serum specific IgE testing, also known as radioallergosorbent testing (RAST), is performed to detect allergen-specific IgE in the blood. Specific IgE ≥ 15 kU/L is highly predictive of peanut allergy [4].

These tests do not predict the severity of clinical allergy [4].

An IgE-mediated type I hypersensitivity reaction and ensuing anaphylaxis can be due to other causes. For example:

The sudden development of a rash might be due to the non-allergic release of histamine, as in scombroid fish poisoning.

The treatment of anaphylaxis is a medical emergency entailing the stabilisation of airway, breathing, and circulation.

Confirmed peanut allergy needs a comprehensive management plan, which should be shared with the patient's wider family, school, and/or workplace [4,15,16].

Adrenaline injection

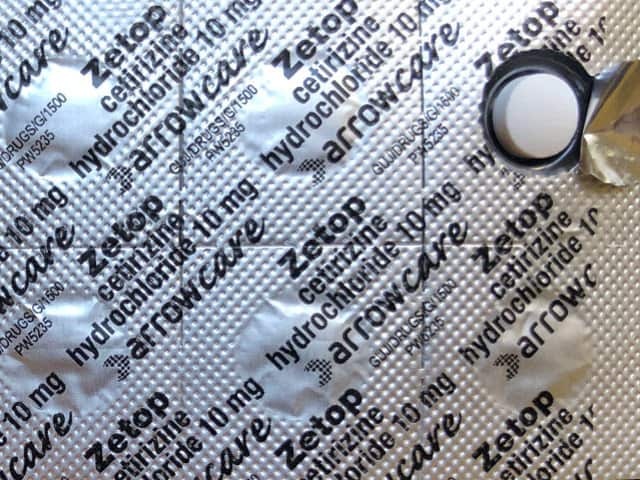

Antihistamine tablets

The eating or touching of peanuts, peanut butter, peanut flour, arachis oil, and other peanut-containing products must be completely avoided by the patient. Ingredient lists and warnings on manufactured food must be read (in New Zealand, the USA, and many other countries, the possibility of an item containing peanuts must be declared on the packet). Patients need to be particularly careful when eating away from home, where unintended contamination of other foods with peanuts may occur.

It is unclear whether patients with peanut allergy should also avoid all legumes and tree nuts.

Antihistamines should be carried at all times and taken if an allergic reaction occurs. The patient and their carers should be regularly trained in how to use an adrenaline auto-injector or adrenaline in a prepared syringe, and if the device has to be used, the patient must seek immediate medical attention [4].

Between 5% and 9% of siblings of children with a peanut allergy will also have a peanut allergy. In individuals at high risk of an allergic reaction (those with asthma, eczema, or other food allergies) or in cases of parental anxiety, it is advisable to perform skin prick testing or specific IgE testing before the child introduces peanut into their diet. In individuals at low risk of an allergy, peanuts can be carefully introduced to test for any allergic reaction [4].

Clinical trials of oral, sublingual, and epicutaneous peanut immunotherapy have shown some promising results, but at present, this is not routinely offered as a treatment for peanut allergy [4].

Humanised anti-IgE monoclonal antibody therapy using omalizumab has been shown to speed up desensitisation in peanut immunotherapy [17].

About 20% of children with their allergy will grow out of peanut allergy [10]. The allergy persists into adult life in the majority of affected individuals.