Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Prader-Willi syndrome — extra information

Prader-Willi syndrome

Author: Dr Delwyn Dyall-Smith, Dermatologist, Wagga Wagga, NSW, Australia. DermNet Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell/Maria McGivern. January 2018.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

Cutaneous features

Diagnosis

Complications

Differential diagnoses

Management

What is Prader–Willi syndrome?

Prader–Willi syndrome is the most common genetic cause of obesity. It was first described in 1887 by John Langdon Down, 70 years before Prader et al in 1956. It is also known as Prader–Labhart–Willi syndrome.

Eugenia Martínez Vallejo, clothed by Don Juan Carreño de Miranda (c. 1680).

* Credit: Museo Nacional del Prado.

Who gets Prader–Willi syndrome?

Prader–Willi syndrome is reported to occur approximately once in 25,000 live births, but it is likely to be more common due to a failure to diagnose the condition early.

Prader–Willi syndrome has autosomal dominant inheritance, (is inherited from one affected parent) and affects both sexes and all races. However, most cases are sporadic.

What is the cause of Prader–Willi syndrome?

Prader–Willi syndrome results from the lack of expression of the PWC region of chromosome 15. The genes for Prader–Willi syndrome are normally expressed only on the chromosome inherited from the father, and the copy of chromosome 15 inherited from the mother is switched off.

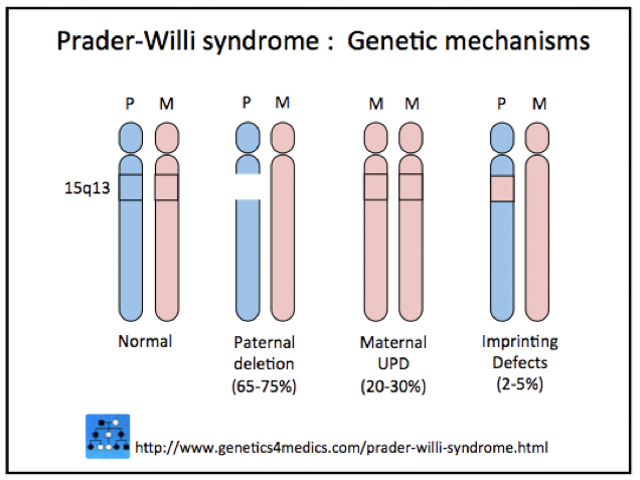

Three mechanisms are involved.

- In 75% of cases, the lack of Prader–Willi genes is inherited from an unaffected father (ie, paternal 15q11-q13 deletion).

- In 20%, both copies of chromosome 15 are inherited from the mother (ie, maternal uniparental disomy [mUPD])

- In 5%, inactivation of these genes is due to an imprinting defect in the father’s Prader–Willi critical region of chromosome 15.

Angelman syndrome is a clinically distinct disorder that results from a maternally derived imprinting defect mapped to the same chromosome as Prader–Willi syndrome.

Genetic mechanisms of Prader–Willi syndrome

*Image courtesy Genetics 4 Medics.

What are the clinical features of Prader–Willi syndrome?

The clinical features of Prader–Willi syndrome depend on the age of the individual.

Infancy

- Difficulty feeding and poor sucking reflex

- Diminished or absent crying

- Sleepiness

- Floppiness

- Delayed early developmental milestones

- Failure to thrive

- Facial features that include almond-shaped eyes, a down-turned mouth, a narrow distance between the temples, and a thin upper lip

- Hospital admissions for chest infections.

Childhood

- Food-seeking behaviour leading to obesity

- Short height

- Temper tantrums

- A high pain threshold

- Sleep disturbances

- Skin picking

- Squint

- The characteristic facial appearance becomes more obvious

- Small hands and feet, with thin tapering fingers and toes

- Intellectual disability

- Hospital admissions for surgery.

Adulthood

- Delayed puberty

- Small or undescended testes, with reduced scrotal folding or wrinkling

- Absent/irregular menstrual cycle

- Orthopaedic problems, including scoliosis or kyphosis of the spine; hip dysplasia; malaligned limbs and bow-leggedness.

Orthopaedic complications of Prader–Willi syndrome

Acquired plate-like osteoma cutis

What are the cutaneous features of Prader–Willi syndrome?

Skin

Skin picking is very common and is the most typical cutaneous feature of Prader–Willi syndrome. Lesions are present at all stages of the evolution of the syndrome. Signs include scratch marks, bleeding, bacterial skin infection, scabs, scarring, and secondary milia — especially on the backs of the hands and forearms.

Other cutaneous features may include:

- Marked skin mottling in newborns

- Lightly coloured skin, hair and eyes (Fitzpatrick skin type I–II)

- Abdominal striae (stretch marks) related to obesity/overeating in childhood

- Erysipelas, especially in the older age group

- Panniculitis

- Leg swelling and oedema with varicose veins

- Piezogenic papules, reported in four of every five patients examined

- Bruising due to high pain threshold

- Hypogonadism, resulting in reduced or absent facial, armpit, and pubic hair, especially in males

- Hair whorls in the anterior scalp

- Skin signs of diabetes mellitus, including acanthosis nigricans.

There are also single case reports of urticaria pigmentosa, extremely dry skin, seborrhoeic dermatitis, and pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.

Mouth

Features of Prader–Willi syndrome can include:

- Thick saliva at the edges of the mouth

- Small teeth with poorly developed enamel, resulting in dental caries

- A high arched palate.

Anogenital region

Features of Prader–Willi syndrome can include:

- Rectal skin picking, with consequent bleeding, ulcers, anaemia, and constipation

- Poorly developed vulval labia (lips) in females

- Reduced scrotal wrinkling and folding in males.

Skin conditions that can affect people with Prader–Willi syndrome

Skin picking

Abdominal striae

Erysipelas

How is Prader–Willi syndrome diagnosed?

The following diagnostic criteria may be used to diagnose Prader–Willi syndrome.

Major criteria

Each of the following criteria scores 1 point:

- Characteristic facial features: almond-shaped eyes, down-turned mouth, a narrow distance between the temples, and a thin upper lip

- Delayed developmental milestones

- Feeding problems or failure to thrive in infancy

- Hypogonadism (underactive sex hormones)

- Floppy at birth

- Rapid weight gain between 1 and 6 years of age.

Minor criteria

Each of the following criteria scores 1 point:

- Decreased fetal movements and infantile lethargy

- Eyes and vision problems, including squint and short-sightedness

- Pale skin, hair, and eye colour (compared with other family members)

- Narrow hands with a straight ulnar border

- Short height (compared with other family members)

- Skin picking

- Sleep disturbance or sleep apnoea.

Investigations

Genetic studies are the most accurate way to diagnose Prader–Willi syndrome. Such studies should be considered in any floppy newborn baby requiring tube feeding. All three mechanisms for the syndrome should be looked for sequentially, starting with the paternal deletion.

X-rays should be undertaken during childhood to identify skeletal problems, as these can be masked by obesity.

What are the complications of Prader–Willi syndrome?

In adult life, dermatological problems requiring treatment are a major health issue, with erysipelas being a common reason for hospital admission.

Medical complications of Prader–Willi syndrome include:

- Morbid obesity

- High blood pressure

- Stroke

- Deep vein thrombosis (leg clots)

- Pulmonary embolus (clots to the lungs)

- Heart attacks

- Anxiety

- Chest infections and pneumonia

- Diabetes mellitus type 2

- Osteoporosis and osteopenia

- Abnormal drinking patterns, leading to water intoxication

- Inability to vomit.

Differential diagnosis of Prader–Willi syndrome

The differential diagnosis of Prader–Willi syndrome includes other causes of obesity and failure to thrive in infancy and childhood.

6q16 deletion syndrome

One Prader–Willi-like syndrome to be considered is 6q16 deletion syndrome, which is due to proximal deletions of the long arm of chromosome 6. Its main features are:

- Obesity and excessive eating

- Hypotonia

- Small hands and feet

- Eye and vision problems

- Global developmental delay.

What does the management of Prader–Willi syndrome involve?

Genetic counselling is recommended for future pregnancies and family members. Special care may be needed with general anaesthesia for individuals with Prader–Willi syndrome. Treatments deal with medical and surgical complications and associations as they arise and are related to the affected individual's age.

Infancy

- Treatment may be required for difficulty with feeding and floppiness (eg, tube feeding)

- Respiratory infections are also common in this age group.

Childhood

- The most common causes of hospital admission in Prader–Willi syndrome are related to the disease (eg, orthopaedic correction).

- The management of obsessive eating, leading to excessive weight gain and other behavioural disorders, becomes a major issue for families.

Adolescence

Hospital admissions may be required for:

- Hormone-related issues (eg, growth hormone deficiency)

- Scoliosis surgery.

Adults

Hospital admission may be required for:

- Surgery for an inguinal hernia

- Medical events related to diabetes mellitus and skin infections (eg, erysipelas)

- Psychiatric episodes

- Water or drug intoxication.

Medications used by adults with Prader–Willi syndrome include psychotropics, laxatives, skin products, and treatments for diabetes.

Older people

Respiratory infections are a major health issue in older adults.

References

- Bornhausen-Demarch E, Célem L, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Prader–Willi syndrome. Cutis 2012; 90(3): 129–31. PubMed

- Fowler J, Butler M. Urticaria pigmentosa in a child with Prader–Labhart–Willi syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989; 21: 147–8. PubMed

- Hurren BJ, Flack N. Prader-Willi syndrome: A spectrum of anatomical and clinical features. Clin Anat 2016; 29: 590–605. DOI: 10.1002/ca.22686. PubMed

- Sakthivel M, Hughes SM, Riley P, et al. Severe neonatal onset panniculitis in a female infant with Prader–Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2011; 155: 3087–9. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34318. PubMed.

- Samlaska C, James W, Sperling L. Scalp whorls. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989; 21(3 Pt 1): 553–6. PubMed

- Schepis C, Greco D, Siragusa M, Romano C. Piezogenic pedal papules during Prader–Willi syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2005; 19: 136–7. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01048.x. PubMed

- Sinnema M, Maaskant MA, van Schrojenstein Lantman-deValk HMJ et al. Physical health problems in adults with Prader–Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2011; 155: 2112–24. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34171. PubMed

- Walker JD, Warren RE. Necrobiosis lipoidica in Prader–Willi-associated diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 2002; 19: 884–5. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.07813.x. PubMed

- Wattendorf DJ, Muenke M. Prader-Willi syndrome. Am Fam Physician 2005; 72: 827–30. Journal

- Cassidy SB, Dykens E, Williams CA. Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes: sister imprinted disorders. Am J Med Genet 2000; 97(2): 136–46. PubMed.

On DermNet

Other websites

- Prader-Willi syndrome; PWS. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM)

- Anticipatory guidance for parents of Prader–Willi children — Medscape Pediatric Nursing

- Prader-Willi syndrome — Medscape

- Prader-Willi syndrome — Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center

- Prader-Willi syndrome anaesthesia guidelines in English and German — OrphanAnesthesia anaesthesia guidelines in English and German

- Prader-Willi syndrome — Gene Reviews

- Prader-Willi syndrome — Genetics Home Reference

- Foundation for Prader-Willi Research

- Eugenia Martínez Vallejo, clothed by Don Juan Carreno de Miranda (c. 1680) — Museo del Prado (Eugenia is believed to have suffered from Prader–Willi syndrome)