Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Dr Cindy Towns, University of Otago and Wellington Hospital, New Zealand. Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, New Zealand, June 2020. Updated by Dr Ian Coulson, Dermatologist, UK, July 2023.

Introduction - porphyria Introduction Demographics Causes Clinical features Complications Diagnosis Treatment

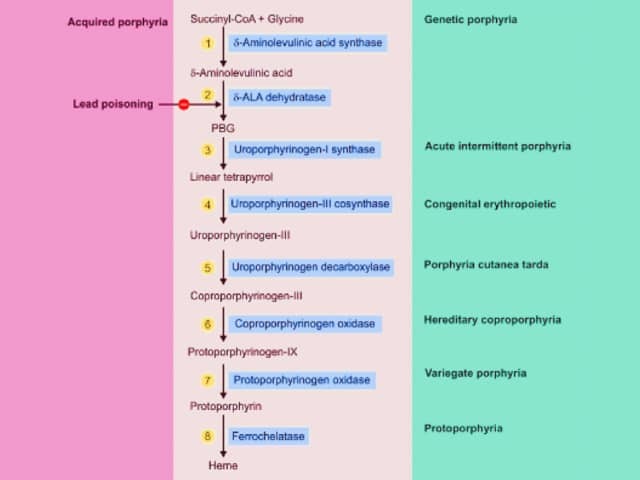

Porphyrias are a group of inherited metabolic disorders in which there is a build-up of haem precursors. They are classified into the acute hepatic porphyrias and the chronic cutaneous types of porphyria.

Specific enzyme deficiencies in the haem pathway result in specific clinical presentations.

Heme synthesis porphyria

There are 4 acute hepatic porphyrias. They are characterised by recurrent acute attacks of severe ‘neurovisceral’ abdominal pain.

The three autosomal dominant acute hepatic porphyrias are:

The presentation, initial diagnosis, and management of acute attacks are identical for AIP, VP, and HCP. Skin lesions can occur in variegate porphyria and hereditary coproporphyria, but do not occur in acute intermittent porphyria.

Delta aminolaevulinic acid dehydratase porphyria, a hepatic porphyria resulting from low levels of the enzyme delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase, has autosomal recessive inheritance with very few case reports in the literature and is not considered here.

Acute intermittent porphyria, variegate porphyria, and hereditary coproporphyria occur globally, but some regions have higher prevalence due to founder effects (eg, acute intermittent porphyria in Sweden and variegate porphyria in South Africa). Worldwide, acute intermittent porphyria is the most common form of acute hepatic porphyria and hereditary coproporphyria is the least common. Both sexes are equally affected.

Most patients with acute porphyria will not suffer acute attacks — penetrance is low at 10% or less.

The porphyrias are due to inherited mutations in the haem synthesis pathway. The reduced enzymatic function results in a build-up of haem precursors.

The accumulation of aminolaevulinic acid and porphobilinogen is believed to cause the neurovisceral features, but the pathophysiology is poorly understood.

Acute attacks occur when the first enzyme in the pathway, aminolaevulinic acid synthase (ALAS1), is induced. Triggers include:

The three autosomal dominant forms of acute porphyria have similar clinical features.

Porphyria attacks can range from mild to severe. Patients typically describe severe but diffuse abdominal pain during attacks. Similar pain can occur in the proximal limbs and back.

Non-specific symptoms are common, such as subjective sensory changes, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Up to 60% of patients with an acute porphyria will develop chronic pain between attacks.

Variegate porphyria and hereditary coproporphyria may have skin lesions in the context of an acute neurovisceral attack or separately. They are similar to those found in porphyria cutanea tarda.

The most common skin symptom is photosensitivity. Blistering, erosions, and milia may also occur.

Variegate porphyria

Variegate porphyria

Complications of porphyria can include:

Longer-term complications include:

Given the severity and recurrent nature of the pain, porphyria patients may be at increased risk of opioid misuse and dependence.

Porphyria may be suspected clinically, but must be confirmed by laboratory tests.

The most important immediate test is a measurement of light-protected urinary porphobilinogen.

Urinary porphyrins may also rise in an acute attack, but are less specific as urinary porphyrins may occur in infections, hepatobiliary disease, haematological disorders, heavy metal exposure, and lead poisoning.

Once an acute attack is confirmed, blood and faecal samples are tested to determine the subtype of porphyria. Samples should be sent to an accredited laboratory or one familiar with porphyria testing (listed on the Australia Porphyria Association website).

A skin biopsy of cutaneous lesions in variegate porphyria and hereditary coproporphyria has similar findings to porphyria cutanea tarda.

Screening of relatives is essential as the majority of people with the genetic mutation will have clinically latent disease but are at risk of developing acute attacks and should heed the same advice regarding triggers.

More recently, genetic testing of patients and relatives has been introduced – ALAD, HMBS,CPOX and PPOX for ALAD, AIP, HCP and VP respectively.

The pain of acute attacks can be severe, requiring hospitalisation for pain management and a work-up for other possible causes of pain. Severe electrolyte imbalance, respiratory distress, or seizures should prompt admission to intensive care.

Recommended treatments to suppress ALAS1 include:

Drugs that are potential triggers of acute attacks must be avoided. The drugs below are considered safe at the time of writing (June 2019).

Pain-management drugs that are safe to use during treatment for acute porphyria include:

Anti-emetics that are safe to use during treatment for acute porphyria include:

Anticonvulsants that are safe to use during treatment for acute porphyria include:

Sun protection is important for patients with cutaneous porphyria, using covering clothing and an opaque sunscreen that blocks visible light. Topical dihydroxyacetone (tanning cream) may also be useful in blocking some of the visible light. Vitamin D supplements may be required.

All porphyria patients should wear a medical alert bracelet.

Porphyria patients have increased risk for hypertension and renal impairment as well as hepatocellular cancer; some services recommend annual screening with liver ultrasound after the age of 50.

Givosiran is a synthetic small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA) molecule currently in clinical trials. It has been shown in clinical trials to reduce aminolaevulinic acid and porphobilinogen as well as decrease acute attacks and is now licensed by the FDA for the prophylactic management of those who have frequently recurring acute attacks. Rarely, liver transplantation has been utilised for progressive recalcitrant disease unresponsive to haemin or givosiran and is curative.