Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Dr Louise Reiche, Dermatologist, Palmerston North, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. December 2020.

Introduction Metabolisation of collagen Collagen and aging How to optimise skin collagen Foods required to make collagen Other measures to improve skin collagen

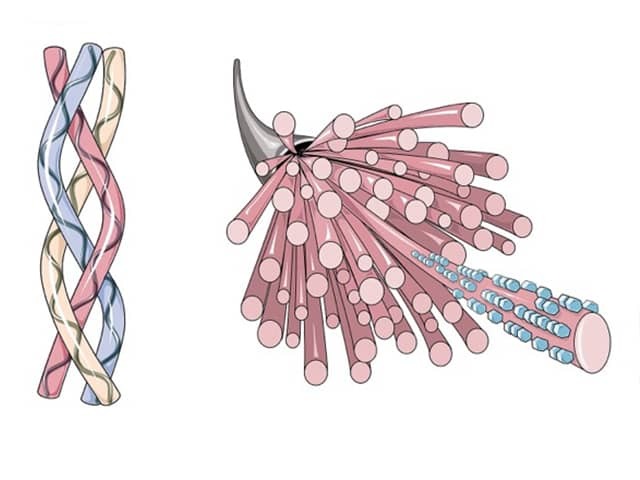

Collagen is the main protein in many structural supportive connective tissues in the body such as skin, bones, ligaments, tendons, and muscle. It consists of protein fibrils wound in a strong triple helical structure. Collagen constitutes at least 70% of the dry weight of human skin.

Many different types of collagen have been identified. Type I is the major form of collagen found in the dermis, providing tensile strength in the skin. Type III is the other main dermal collagen particularly in fetal skin. Types IV and VII are important in the basement membrane zone of skin.

Structure of collagen

Collagen is synthesised in the skin by dermal fibroblasts, linking amino acids into a sequence of either glycine-proline-X, or glycine-X-hydroxyproline. Every third amino acid in collagen is glycine and 20% are either proline or hydroxyproline; X can be any other amino acid. Glycine is the smallest amino acid, enabling the protein alpha chain to form a strong tight helical configuration. Hydroxylase enzymes add hydroxyl groups to proline and lysine using cofactor vitamin C. Hydroxyproline is unique to collagen. Glucose and galactose moieties are attached to selected lysine hydroxyl groups in a process called glycosylation. Three alpha helix chains coil upon each other into a triple helical structure. Outside the fibroblast, this propeptide collagen is trimmed by collagen peptidases to form a shortened tropocollagen molecule. In the final step, a copper-dependent enzyme, lysyl oxidase, facilitates the formation of stable crosslinks between lysine and hydroxylysine on separate tropocollagen molecules to give tensile strength to the collagen fibril.

Collagen is continuously turned over. Collagen fibrils break down in response to oxidative cell damage and in the course of normal cellular metabolism involving the enzyme collagenase. A loss of balance between production and destruction of collagen results in reduced tensile strength and formation of wrinkles. Collagen degradation is accelerated by poor diet and excessive sun exposure. Nutritional deficiencies, such as scurvy, and genetic mutations, as in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and osteogenesis imperfecta, result in construction errors in collagen.

Ingested collagen-rich foods are broken down to 2–3 amino acid oligopeptides (collagen hydrosylates) in the gastrointestinal tract. Oligopeptides and single amino acids are easily absorbed from the bowel into the bloodstream, from where they can be used to construct any required protein. Although the amino acid hydroxyproline is unique to collagen, it may be used to make collagen in any connective tissue, not just the skin.

Skin ageing is associated with a progressive reduction in collagen synthesis and increased collagen degradation. The three-dimensional spatial arrangement of collagen fibrils seen in young skin progressively becomes two-dimensional and the collagen bundles thin and become fragmented and clumped as the skin ages. These changes are accelerated by external factors including ultraviolet (UV) light, pollution, smoking [see Smoking and its effects on the skin], and poor nutrition, resulting in skin dryness and wrinkling.

Ageing proceeds the longer we live, with genetic factors influencing the speed and signs of visible skin ageing.

Two important extrinsic factors influencing visible skin ageing that we can control are sun exposure and diet.

Sun protection measures should start young for maximum benefits, but visible skin ageing can be slowed even if sunsmart behaviour starts in adult life. Wearing a broad-brimmed hat and ultra-protective factor (UPF) 50+ clothing [see Sun protective clothing] covering the trunk and limbs whenever outdoors in daylight will reduce collagen breakdown in skin due to UV light.

A well-balanced diet including protein (0.8–1mg/kg/d), vitamin C, and copper is essential for skin health, particularly with advancing age when absorption and use of essential vitamins, minerals, and amino acids becomes less efficient. A ‘Mediterranean-style diet’ rich in plant-based foods featuring plentiful fresh fruit and vegetables, herbs, nuts, beans, and whole grains; moderate amounts of seafood, dairy, poultry, and eggs; and occasional red meat is associated with good skin health.

Sheep and beef

Varied vegetables, fruits, nuts, and legumes

Lifelong regular good sleep, avoiding smoking, and minimising pollution exposure are additional strategies for slowing signs of skin ageing.

Collagen is a protein found in skin and the musculoskeletal system; foods rich in collagen include bones, red meats (eg, lamb, beef, pork), and white meats (eg, poultry, fish, shellfish). Egg white, marine algae, and spirulina are also sources of collagen. Collagen lacks the essential amino acid tryptophan, so other protein sources such as beans and legumes are required for optimal health.

Vitamin C is a cofactor essential for the synthesis of collagen. Fresh fruit and vegetables including citrus fruit, berries, kiwifruit, and beetroot, are rich sources of vitamin C.

Minerals including copper are also important in collagen production. Natural food sources of copper include shellfish, nuts such as cashews, grains and seeds, fruit and vegetables including avocado, chickpeas, sweet potatoes, mushrooms, and tofu.

Nutrients such as vitamins and minerals are best absorbed from fresh food sources compared to manufactured foods or supplements. Protein-deficient diets may benefit from collagen supplements.

Studies using oral supplements of collagen hydrosylates have typically shown better results than large collagen molecules and topical formulations, for reducing signs of skin dryness and wrinkling, especially if they also contain other nutrients such as vitamin C. Collagen can be derived from animal and marine sources. Marine sources of collagen may be preferred due to their better absorption and lower risk of biological contaminants. Attention to the country of origin of collagen supplements is important with regard quality, safety, and carbon footprint. Synthetic sources of collagen can be produced in culture from combining mammalian and insect cells, yeasts, and plant cells.

Powdered gelatine

Collagen tonic

Topical retinoids such as retinoic acid and retinaldehyde, increase type I procollagens and decrease metalloproteinases which break down collagen. Retinoic acid increases types I, III, and VII collagen in the dermis and reorganises dermal collagen bundles. In clinical trials, topical retinoids were clinically effective for the treatment of dermal ageing, reducing wrinkles, roughness, and laxity. However, topical retinoids can sometimes irritate the skin.

Topical alpha-hydroxy acids (AHA) and dermal rejuvenation using fractional lasers and radiothermoplasty can also stimulate collagen production to some degree.

Injected collagen fillers derived from bovine collagen or cultured human fibroblasts are used to soften lines and furrows [see Collagen replacement therapy].