Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Dr Katrin Platzer, Foundation Year 2 Doctor, Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust, Torquay, UK. DermNet Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. March 2018.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

What are the dermatological findings in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome?

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome (VKH) is a multisystem disease that presents with a combination of ophthalmological, neurological, and dermatological signs and symptoms.

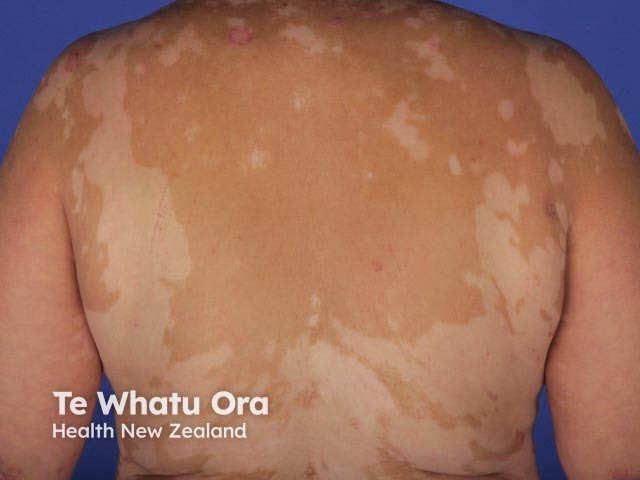

Vitiligo

Vitiligo

Vitiligo + psoriasis

VKH is reported to have significant regional and global variation [1]. VKH is more prevalent in patients with a darker skin pigmentation than in Caucasians and people of Turkish descent. Patients with VKH are most commonly of Asian, Hispanic, Indian, Native American, or Mediterranean origin [2]. There are twice as many females affected by VKH as males [3].

VKH is mainly diagnosed in adult and middle-aged patients aged 20–50, although onset in childhood or old age has also been reported [4–6].

The exact cause of VKH is yet to be established. It is an autoimmune inflammatory condition mediated by CD4+ T cells targeting melanocytes [7,8]. Genetic predisposition and/or an unspecified exposure to a virus may be involved [1].

Classically, VKH has four clinical stages. The clinical features vary, depending on ethnic group. Dermatological features are most often noted in the chronic convalescent stage [1].

The prodromal stage of VKH may mimic viral infection and lasts for 1–2 weeks [2]. The symptoms are mainly neurological, and include:

Auditory symptoms include:

The acute stage of VKH affects the eye and lasts for several weeks [2].

Many patients with acute VKH go on to the chronic convalescent stage of VKH, about 3–4 months after the onset of the disease [9,10]. This usually lasts for some months or years [1,2].

25% of patients with acute VKH develop the chronic recurrent phase of the disease 6–9 months after initial presentation [1,2].

About 30% of patients with VKH develop dermatological findings [12]. Vitiligo, poliosis, and alopecia areata usually occur in the chronic convalescent stage of the disease [13].

Patients with VKH can develop complications that threaten or impair vision, such as:

The diagnostic criteria for VKH include inflammation of both eyes without evidence of another ocular disease, a history of trauma, or ocular surgery [17].

There are three distinct categories of the disease [17]:

Differential diagnoses for the ophthalmological signs and symptoms of the disease include:

Acute VKH should be treated aggressively with a systemic corticosteroid (minimum treatment duration is 6 months), combined with a corticosteroid-sparing agent, such as ciclosporin, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil [1]. Anti–tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF) agents or other biological agents can be considered in patients who do not respond to corticosteroids combined with corticosteroid-sparing agents [1].

The aim of treatment is to dampen the inflammatory response and to prevent ocular complications, such as sunset glow fundus, cataracts, glaucoma, and choroidal neovascularisation [1].

Better visual outcomes are described in those patients who undergo prompt and aggressive treatment of VKH. However, a significant proportion of patients still develop vision-impairing complications. Cataracts and glaucoma often require surgical management [1,2].

Favourable prognostic factors include good initial visual acuity and initiation of treatment in the acute rather than chronic recurrent stage of the disease [11,15,19].