Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Authors: Dr Sarah Elyoussfi, Dermatology Registrar; Dr Ian Coulson, Consultant Dermatologist, East Lancashire NHS Trust, United Kingdom. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. March 2022

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms and signs of specific organ involvement

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis

Prognosis

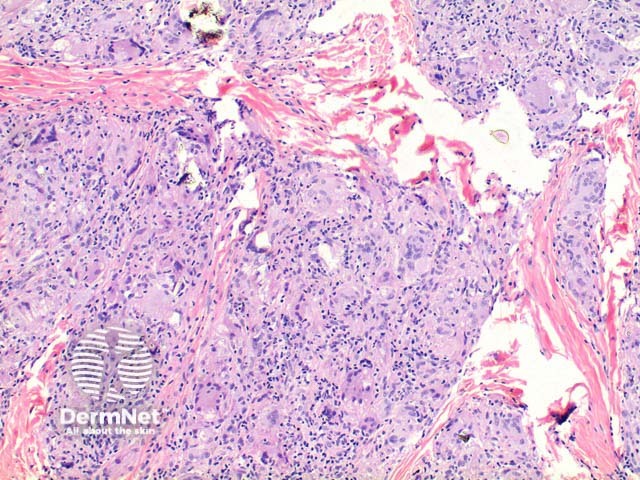

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease characterised by granulomas in various organs. Characteristically, these are non-caseating epithelioid granulomas (a pathological description distinguishing sarcoidal granulomas from the caseating or cheese-like granulomas seen in tuberculosis).

Sarcoidosis can affect a variety of organs with varying frequencies, including:

Fever and a rash

Bihilar lymphadenopathy in sarcoidosis

Plaque sarcoid on the cheek and nose

Sarcoidosis

Lupus pernio in cutaneous sarcoidosis

Scar sarcoid mimicing a keloid on a pierced ear lobe

Sarcoidosis occurs worldwide, affecting persons of all races, ages, and sex.

No single cause has been identified. Many researchers have hypothesized the role of genetics, environmental factors, and autoimmunity in the development of sarcoidosis.

Eleven sarcoidosis genetic risk loci (BTNL2, HLA-B, HLA-DPB1, ANXA11, IL23R, SH2B3/ATXN2, IL12B, NFKB1/MANBA, FAM177B, chromosome 11q13.1, and RAB23) have been identified.

Several HLA and non-HLA alleles are associated with the development of this disease such as HLA-DRB1*0301/ DQB1*0201, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4). Monozygotic twins with sarcoidosis have an 80-fold higher risk of also developing sarcoidosis.

Exposure to substances such as wood stoves, soil, tree pollen, inorganic particulates, insecticides, and silica have been associated with an increased risk of developing sarcoidosis.

It has been suggested that certain bacteria may trigger sarcoidosis including Mycoplasma species, Leptospira species, herpes virus, retrovirus, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Borrelia burgdorferi, Pneumocystis jirovecii, and Propionibacterium species.

Drug-induced sarcoidosis-like reactions have been reported with a number of medications, including checkpoint inhibitors, and anti-TNF and anti-interleukin biological agents. Sarcoidosis appears to be more common in those suffering from vitiligo.

Sarcoidosis can affect any organ therefore patients may present with a wide variety of symptoms.

Sarcoidosis may not result in any symptoms and the disease may come and go without the patient or doctor ever being aware of it. Symptoms can appear suddenly and then just as quickly resolve spontaneously. Sometimes, however, they can continue over a lifetime.

Non-specific general symptoms like fatigue are seen in nearly 70% of patients. Other constitutional symptoms may include:

More than 20% of patients have peripheral lymphadenopathy. The affected lymph nodes are moderately swollen and are usually painless.

Sarcoidosis may involve one organ system or several.

Non-specific lesions include:

Specific lesions show granulomas on histology (microscopic examination of a skin biopsy) and include:

Any part of the eye can be involved:

Uncommonly, cataracts, glaucoma, and blindness can result.

Plaque sarcoid on the dorsal hand

Extensive cutaneous sarcoidosis

Plaques of sarcoid on the cheeks mimicing basal cell carcinomas

Nasal rim sarcoid papules

Papular sarcoid of the lids

Sarcoid nail dystrophy

Sarcoidosis pathology

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is based on three major criteria:

There is no established “gold standard” investigation, however the following may be performed when sarcoidosis is suspected; results must be taken in combination with the history and examination.

The differential diagnosis includes:

For most patients with sarcoidosis, no treatment is required. Symptoms are not usually disabling and tend to disappear spontaneously. Surveillance for 3–12 months is typically advised to determine the overall course of the disease. Treatment is indicated only when symptoms are disabling and/or the granulomatous inflammation is causing life-threatening organ involvement.

Most will recover in a short time frame whilst a small number do not recover after 2–5 years. These chronic patients frequently need long-term treatment.

Erythema nodosum, the common nonspecific cutaneous lesion, is usually self-limiting. Short-course nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or glucocorticoids may be prescribed to treat pain and discomfort.

Sarcoidosis-specific cutaneous lesions can improve spontaneously. Cutaneous lesions are treated only if they cause significant cosmetic disfigurement, psychological effects, or if the lesions are progressive. Treatment is as follows:

Two-thirds of patients report a self-remitting disease within 12 to 36 months. The remainder of patients may follow a chronic course (10 to 30% require prolonged treatment). With correct diagnosis and proper management, most patients with sarcoidosis continue to lead a normal life.

Cutaneous sarcoidosis usually has a more prolonged course. Papules and nodules tend to resolve over months or years. Plaques may be more resistant. Lupus pernio is often present in patients with chronic sarcoidosis and is associated with involvement of the upper respiratory tract, advanced lung fibrosis, bone cysts, and eye disease.

Factors associated with poor prognosis include: ethnicity (particularly African American and Afro Caribbean origins), age over 40 years at presentation, lupus pernio, chronic uveitis, CNS involvement, cardiac involvement, severe hypercalcemia, nephrocalcinosis, and radiographic stages III and IV.

In Western countries, most sarcoidosis deaths are due to advanced pulmonary fibrosis leading to respiratory failure and/or pulmonary hypertension and less commonly, cardiac and CNS sarcoidosis or portal hypertension. In addition to treatment-related mortality, less common causes of death include lymphoma and haemoptysis due to mycetoma.