Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Juhee Roh, Post Graduate Year 2 House Officer, Waitemata District Health Board, Auckland, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. November 2020.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

Dermoscopy features

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

Paediatric alopecia areata is an autoimmune form of nonscarring hair loss defined as being in childhood if the onset is by 10 years of age, or adolescence if between 11 and 20 years.

Alopecia areata is common worldwide, affecting all races and both sexes. Approximately 2% of the general population will have alopecia areata at some point in their lives, and 60% of them will develop their first patch of hair loss before the age of 20 years. Prevalence peaks between 10 and 30 years of age. Large series have suggested paediatric-onset alopecia areata is more common in girls than boys, but is more severe in boys. Congenital alopecia areata has been reported.

Alopecia areata developing in the first ten years of life is strongly associated with atopic dermatitis (approximately one-third) and lupus erythematosus. In the teenage years, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis are also associated. Thyroid disease and other autoimmune conditions are not detected at increased incidence in children with alopecia areata, in contrast with adult-onset disease.

Alopecia areata is considered to be an organ-specific autoimmune condition of the hair follicle on a genetic background.

Alopecia areata often runs in families, and has been reported in monozygotic twins. Up to 25% of children will have at least one affected family member, and many have multiple relations with alopecia areata. It is reported to be common in Down syndrome and Turner syndrome — autoimmune disease is particularly common in Turner syndrome. This suggests a genetic predisposition to developing alopecia areata. However, investigations suggest the association is complex and polygenic.

Many hypotheses have been proposed attempting to explain the development of alopecia areata, but at this time the detailed pathogenesis is not understood.

Children typically present with a sudden onset of a solitary patch of hair loss, most commonly on the scalp, characterised by:

Alopecia areata can present with multiple patches on any hair-bearing body site, including eyebrows and eyelashes.

Patterns of alopecia areata include:

Patchy alopecia areata in a child

Eyebrow loss in alopecia areata

Ophiasis pattern of alopecia areata

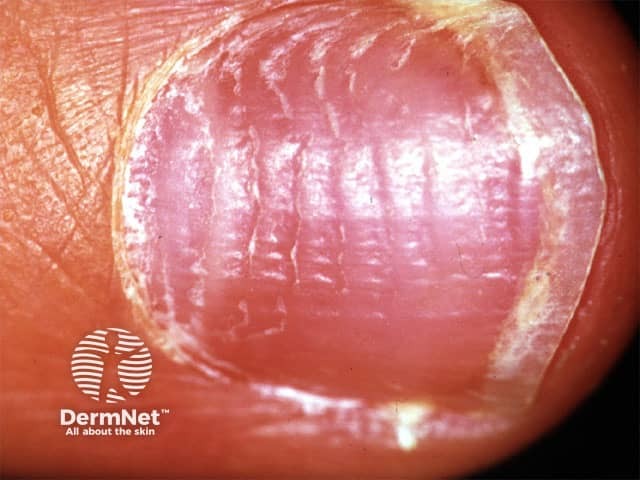

Nail changes were seen in almost 50% in one large series of children with alopecia areata, particularly pitting and trachyonychia (see Nail terminology). Nail changes do not correlate with the severity of the alopecia areata.

Alopecia areata nail pitting

Trachyonychia

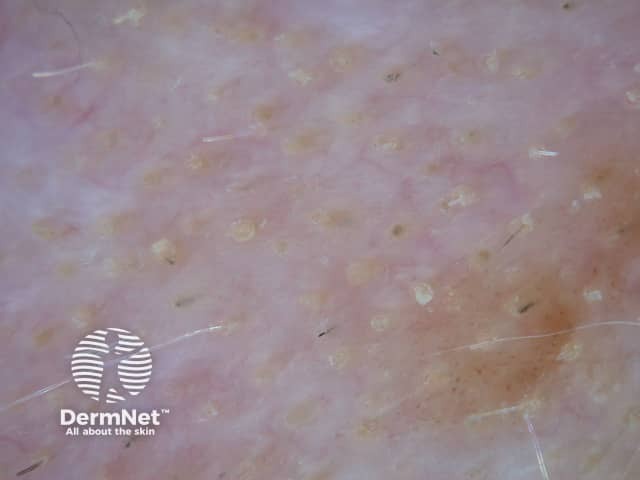

Exclamation mark hairs at edge of patch

Yellow dots, black dots, and short hairs

Social and psychological effects are common with any form of hair loss in children and can have a serious impact on quality of life. Social isolation, humiliation by peers, low self-esteem, anxiety, stress, and depression are often associated with alopecia areata. Paediatric alopecia areata also has a significant impact on the family as a whole (see Psychological effects of hair loss).

Alopecia areata is usually a clinical diagnosis confirmed using trichoscopy. Wood light examination and examination of plucked hairs or skin scrapings may be required to exclude tinea capitis (see Laboratory tests for fungal infections). Skin biopsy is rarely required in children. Blood tests may be considered if there are concerns about coeliac disease or other associated autoimmune conditions.

The two most important differential diagnoses in children presenting with patchy nonscarring hair loss are:

No treatment changes the natural history of alopecia areata. ‘Wait and see’ is a reasonable option in young children with limited disease, as up to 50% show regrowth within one year. Options for alopecia areata in children include the following treatments.

A wig may be necessary for extensive hair loss. Referral to a psychologist should be considered when there is significant psychological distress.

Up to 50% of patients show regrowth within one year without treatment, but the course is unpredictable. Relapse is common even after apparently successful regrowth after treatment. Young age at first presentation is associated with a poor prognosis.

Other poor prognostic factors include: