Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Alopecia areata in children — extra information

Alopecia areata in children

Author: Juhee Roh, Post Graduate Year 2 House Officer, Waitemata District Health Board, Auckland, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. November 2020.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

Dermoscopy features

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

What is paediatric alopecia areata?

Paediatric alopecia areata is an autoimmune form of nonscarring hair loss defined as being in childhood if the onset is by 10 years of age, or adolescence if between 11 and 20 years.

Who gets paediatric alopecia areata?

Alopecia areata is common worldwide, affecting all races and both sexes. Approximately 2% of the general population will have alopecia areata at some point in their lives, and 60% of them will develop their first patch of hair loss before the age of 20 years. Prevalence peaks between 10 and 30 years of age. Large series have suggested paediatric-onset alopecia areata is more common in girls than boys, but is more severe in boys. Congenital alopecia areata has been reported.

Alopecia areata developing in the first ten years of life is strongly associated with atopic dermatitis (approximately one-third) and lupus erythematosus. In the teenage years, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis are also associated. Thyroid disease and other autoimmune conditions are not detected at increased incidence in children with alopecia areata, in contrast with adult-onset disease.

What causes alopecia areata in children?

Alopecia areata is considered to be an organ-specific autoimmune condition of the hair follicle on a genetic background.

Alopecia areata often runs in families, and has been reported in monozygotic twins. Up to 25% of children will have at least one affected family member, and many have multiple relations with alopecia areata. It is reported to be common in Down syndrome and Turner syndrome — autoimmune disease is particularly common in Turner syndrome. This suggests a genetic predisposition to developing alopecia areata. However, investigations suggest the association is complex and polygenic.

Many hypotheses have been proposed attempting to explain the development of alopecia areata, but at this time the detailed pathogenesis is not understood.

What are the clinical features of alopecia areata in children?

Children typically present with a sudden onset of a solitary patch of hair loss, most commonly on the scalp, characterised by:

- Well-defined round or oval shape

- Completely bald smooth surface

- Normal skin appearance

- Exclamation mark hairs at the edge

- Positive hair tug test at the edge if disease is active.

Alopecia areata can present with multiple patches on any hair-bearing body site, including eyebrows and eyelashes.

Patterns of alopecia areata include:

- Patchy

- Reticular

- Ophiasis (occipital) or sisapho (frontal)

- Diffuse

- Alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis.

Alopecia areata patterns of hair loss in children

Patchy alopecia areata in a child

Eyebrow loss in alopecia areata

Ophiasis pattern of alopecia areata

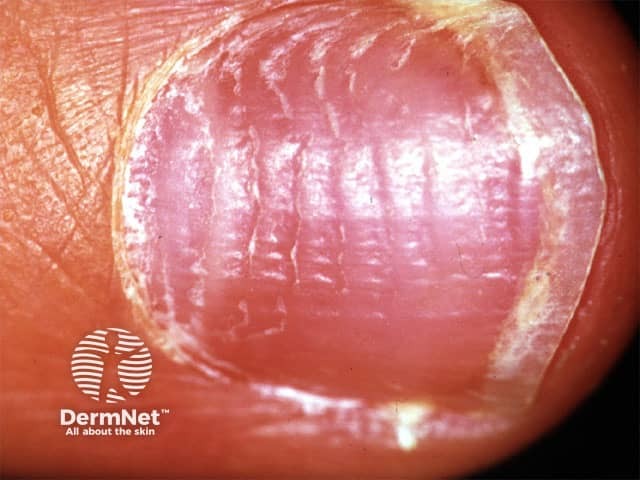

Nail changes were seen in almost 50% in one large series of children with alopecia areata, particularly pitting and trachyonychia (see Nail terminology). Nail changes do not correlate with the severity of the alopecia areata.

Alopecia areata nail pitting

Trachyonychia

What are the dermoscopy features of alopecia areata?

- Yellow dots — sebum and keratin in follicular openings

- Black dots — broken hairs on the scalp surface

- Exclamation mark hairs — narrow at the base, wider at the distal end

- Short regrowing hairs.

Exclamation mark hairs at edge of patch

Yellow dots, black dots, and short hairs

What are the complications of paediatric alopecia areata?

Social and psychological effects are common with any form of hair loss in children and can have a serious impact on quality of life. Social isolation, humiliation by peers, low self-esteem, anxiety, stress, and depression are often associated with alopecia areata. Paediatric alopecia areata also has a significant impact on the family as a whole (see Psychological effects of hair loss).

How is alopecia areata diagnosed in children?

Alopecia areata is usually a clinical diagnosis confirmed using trichoscopy. Wood light examination and examination of plucked hairs or skin scrapings may be required to exclude tinea capitis (see Laboratory tests for fungal infections). Skin biopsy is rarely required in children. Blood tests may be considered if there are concerns about coeliac disease or other associated autoimmune conditions.

What is the differential diagnosis for alopecia areata in children?

The two most important differential diagnoses in children presenting with patchy nonscarring hair loss are:

- Tinea capitis — scaling and inflammation are typically seen

- Trichotillomania — rough, oddly shaped patches of hair loss with broken hairs of varying length.

What is the treatment for alopecia areata in children?

No treatment changes the natural history of alopecia areata. ‘Wait and see’ is a reasonable option in young children with limited disease, as up to 50% show regrowth within one year. Options for alopecia areata in children include the following treatments.

- Potent topical steroids are the mainstay of treatment in children.

- Intralesional steroids may be considered in older children, and short-term systemic corticosteroids in acute rapidly progressive disease.

- Other topical therapies, such as minoxidil, dithranol, calcineurin inhibitors, and immunotherapy such as diphenylcyclopropenone.

- Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, either topical or systemic (such as tofacitinib, baricitanib and ritlecitanib). Baricitanib has received FDA approval for use over the age of 12 in the US, ritlecitanib has been granted NICE approval for over 12s in the UK. Evidence from clinical trials showed nearly 25% of adults and adolescents taking ritlecitinib (Litfulo) saw significant hair regrowth that covered 80% or more of their scalp after 24 weeks (vs 1.6% taking a placebo). After almost a year, the number of patients achieving a response increased further, with over 40% of patients achieving 80% or more scalp hair regrowth. There are some remaining questions however - the endurance of the response and the recurrence of alopecia on drug withdrawal are as yet unanswered.

- Several other oral JAKis are under investigation at present.

A wig may be necessary for extensive hair loss. Referral to a psychologist should be considered when there is significant psychological distress.

What is the outcome for paediatric alopecia areata?

Up to 50% of patients show regrowth within one year without treatment, but the course is unpredictable. Relapse is common even after apparently successful regrowth after treatment. Young age at first presentation is associated with a poor prognosis.

Other poor prognostic factors include:

- Extensive hair loss at presentation, including alopecia totalis and universalis

- Ophiasis pattern of hair loss

- Long duration of hair loss

- Atopy

- Positive family history

- Other autoimmune disease

- Nail involvement.

Bibliography

- Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, McElwee KJ, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update: part I. Clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(2):177–90. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.032. PubMed

- Bains P, Kaur S. The role of dermoscopy in severity assessment of alopecia areata: a tertiary care center study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(4):45–50. PubMed Central

- Brown L, Skopit S. An excellent response to tofacitinib in a pediatric alopecia patient: a case report and review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(8):914–17. PubMed

- Chu SY, Chen YJ, Tseng WC, et al. Comorbidity profiles among patients with alopecia areata: the importance of onset age, a nationwide population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5):949–56. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.032. PubMed

- Cranwell W, Sinclair R. Common causes of paediatric alopecia. Aust J Gen Pract. 2018;47(10):692–6. doi:10.31128/AJGP-11-17-4416. PubMed

- Fernando T, Goldman RD. Corticosteroids for alopecia areata in children. Can Fam Physician. 2020;66(7):499–501. PubMed Central

- King B, Zhang X, Harcha WG, et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2b-3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2023 Jun 10;401(10392):1928]. Lancet. 2023;401(10387):1518–29. PubMed

- Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(3):675–82. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.032. PubMed

- Tosti A, Morelli R, Bardazzi F, Peluso AM. Prevalence of nail abnormalities in children with alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11(2):112–15. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1994.tb00562.x. PubMed

- Wang E, Lee JS, Tang M. Current treatment strategies in pediatric alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57(6):459–65. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.103066. PubMed Central

- Wohlmuth-Wieser I, Osei JS, Norris D, et al. Childhood alopecia areata-data from the National Alopecia Areata Registry. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(2):164–9. doi:10.1111/pde.13387. PubMed

On DermNet

Other websites

- Alopecia areata (hair loss) — AboutKidsHealth

- Alopecia Areata — CS Mott Children's Hospital, Michigan Medicine