Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Authors: Dr Amy Stanway, Department of Dermatology, Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand, February 2004; Updated: Honorary Associate Professor Paul Jarrett, Dermatologist, Middlemore Hospital and Department of Medicine, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, February 2021. Minor internal update May 2023.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

Variation in skin types

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

Atopic dermatitis, also called atopic eczema, the most common inflammatory skin disease worldwide, presents as generalised skin dryness, itch, and rash.

Dry atopic dermatitis in an extensor pattern

Acute flexural atopic dermatitis

Chronic flexural atopic dermatitis

Approximately 230 million people around the world have atopic dermatitis and the lifetime prevalence is >15% especially in wealthier countries. It typically affects people with an ‘atopic tendency’ clustering with hay fever, asthma, and food allergies. All races can be affected; some races are more susceptible to developing atopic dermatitis, and genetic studies are showing marked diversity of the condition’s extent (heterogeneity) between populations.

Atopic dermatitis usually starts in infancy, affecting up to 20% of children. Approximately 80% of children affected develop it before the age of 6 years. All ages can be affected. Although it can settle in late childhood and adolescence, the prevalence in young adults up to 26 years of age is still 5–15%.

Infantile atopic dermatitis on the cheeks

Flexural atopic dermatitis in childhood

Excoriated lichenified atopic dermatitis on the lower back in an adult

Atopic dermatitis results from a complex interplay between environmental and genetic factors [see Causes of atopic dermatitis].

The clinical phenotype of atopic dermatitis can vary greatly, but is characterised by remission and relapse with acute flares on a background of chronic dermatitis.

Acute dermatitis is red (erythematous), weeping/crusted (exudative) and may have blisters (vesicles or bullae). Over time the dermatitis becomes chronic and the skin becomes less red but thickened (lichenified) and scaly. Cracking of the skin (fissures) can occur.

At or shortly after birth, atopic dermatitis may initially present as infantile seborrhoeic dermatitis involving the scalp, and the armpit and groin creases. The skin often feels dry and rough. With time the face, especially the cheeks, and flexures become involved. Young infants cannot scratch and will often rub affected areas, for example the back of the head, causing temporary hair loss. The backs of the hands can be affected due to sucking. The dermatitis is not necessarily confined to these sites and can be more extensive. The napkin area is typically spared due to the moisture retention of nappies, although irritant contact napkin dermatitis can still develop.

Infantile atopic dermatitis, face

Infantile atopic dermatitis, hand

Infantile atopic dermatitis, trunk

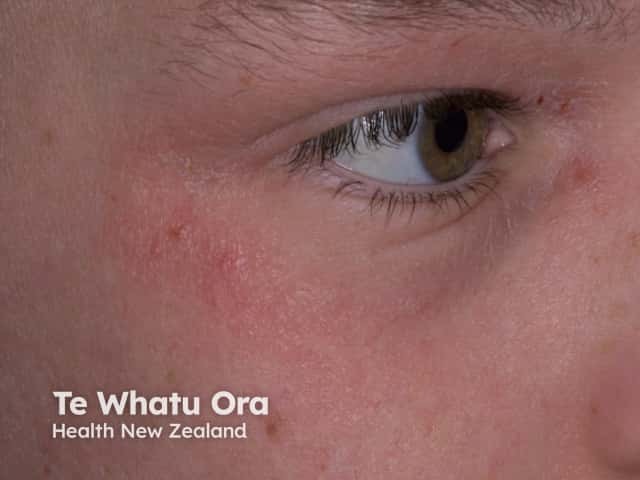

As children grow and develop, the distribution of the dermatitis changes. With crawling, the extensor aspects of the elbows and wrists, knees and ankles are affected. The distribution becomes flexural with walking, particularly involving the antecubital and popliteal fossae (elbow and knee creases). Dribble and food can cause dermatitis around the mouth and chin. Scratching and chronic rubbing can cause the skin to become lichenified (thickened and dry), and around the eyes can lead to eye damage. Pityriasis alba, pompholyx, discoid eczema, pityriasis amiantacea, lip licker’s dermatitis, and atopic dirty neck are various manifestations of atopic dermatitis seen particularly in school-age children and adolescents. During the school years, atopic dermatitis often improves, although the barrier function of the skin is never completely normal [see Barrier function in atopic dermatitis].

Pruritic atopic dermatitis

Atopic cheilitis

Eyelid atopic eczema

Atopic dermatitis of neck

Atopic dermatitis

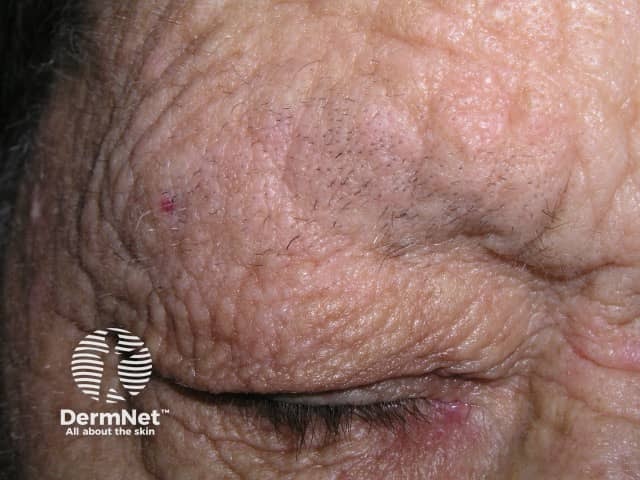

Adult atopic dermatitis can take a variety of forms. It may continue in the school-age flexural pattern or become diffuse. Madarosis, nodular prurigo, and lichenification may follow chronic rubbing. Discoid and papular patterns can develop. For some who had atopic dermatitis in childhood with subsequent complete resolution, it may recur on the hands due to occupational and domestic duties [see Atopic hand dermatitis]. Unusually, atopic dermatitis may develop for the first time in adulthood, as ‘adult onset’ atopic dermatitis. In women and some men, involvement of the nipples and areolae can be problematic [see Nipple eczema].

Atopic hand dermatitis

Lichenified flexural atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis, nipples

Keratosis pilaris, white dermographism, hyperlinear palms, and Dennie-Morgan folds can be useful clues for atopy. A Dennie-Morgan fold is a fold of skin under the lower eyelids due to chronic eyelid dermatitis.

Eyelid contact dermatitis

Atopic eczema

Madarosis due to rubbing of eyebrows

Hyperlinear palm

Lichenification

For more images: Atopic dermatitis images and Atopic flexural eczema images

Dermoscopy of dermatitis shows a patchy distribution of dotted vessels, focal white scales, and yellow serocrust. The yellow-clod sign is seen particularly in acute exudative dermatitis.

Patches of atopic dermatitis in skin of colour

Focal white scale and patchy dotted vessels on dermoscopy

There are ethnic variations in patterns of atopic dermatitis. In Māori, Pacific Islanders, and Africans, the papular variant is observed. Perifollicular and extensor, rather than flexural, patterns may also be more common in patients of African descent.

Conventional scoring systems for atopic dermatitis may underestimate the severity of disease and effects on quality of life in those with skin of colour due to the erythema appearing violaceous. Underestimation may also occur due to cultural factors and communication difficulties between patients, parents, and healthcare providers.

Patients with skin of colour appear to be at particular risk of developing lichen simplex and nodular prurigo with scratching and rubbing.

Postinflammatory hypo- and hyper-pigmentation occurs more commonly with skin of colour and can be more noticeable than in ethnic white skin, resulting in significant psychological distress.

Follicular pattern of atopic dermatitis

Atopic hand dermatitis and follicular pattern on the trunk

Hyperpigmentation due to atopic dermatitis

Postinflammatory hypopigmentation due to atopic dermatitis

Lichenification of atopic dermatitis

Nodular prurigo

Complications of atopic dermatitis are covered in detail on other DermNet webpages.

Eczema herpeticum

Molluscum contagiosum arising in atopic dermatitis

Staphylococcal infection of atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is usually diagnosed clinically and investigations are not required. Patch testing should be considered, particularly if the dermatitis becomes resistant to treatment [see Guidelines for the diagnosis and assessment of eczema, Atopy patch test, Eczema pathology].

EASI and SCORAD are two scoring systems developed to document the severity of atopic eczema.

The list of differential diagnoses for atopic dermatitis is long. A short list of common and important diagnoses to consider in children include:

A more extensive, but still not exhaustive, list is provided in Guidelines for the diagnosis and assessment of eczema.

The treatment of atopic dermatitis is covered in detail on other DermNet webpages: Treatment of atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis affects 15–20% of children and is less common in adults. Sensitive skin persists lifelong. It is impossible to predict whether atopic dermatitis will improve by itself or not in an individual. A meta-analysis including over 110,000 subjects found that 20% of children with atopic dermatitis had persistent disease 8 years later; fewer than 5% had persistent disease 20 years later. Children who developed atopic dermatitis before the age of 2 years had a lower risk of persistent disease than those who developed atopic dermatitis later in childhood or adolescence.

Atopic dermatitis is typically worst between the ages of two and four years, and often improves or even clears after this. However, atopic dermatitis may be aggravated or reappear in adult life due to exposure to irritants or allergens related to caregiving, domestic duties, or certain occupations.