Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Catherine Tian, Medical Student, Department of Dermatology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell/Maria McGivern. November 2018.

Introduction

Causes

Clinical features

Complications

Diagnosis

Treatment

Blue toe syndrome, also known as occlusive vasculopathy, is a form of acute digital ischaemia in which one or more toes become a blue or violet colour. There may also be scattered areas of petechiae or cyanosis of the soles of the feet.

Blue toe syndrome is associated with small vessel occlusion and can occur without obvious preceding trauma or disorders that produce generalised cyanosis, such as hypoxaemia or methaemoglobinaemia [1]. It most often presents in an older man who has undergone a vascular procedure.

Blue toe syndrome: ischaemia

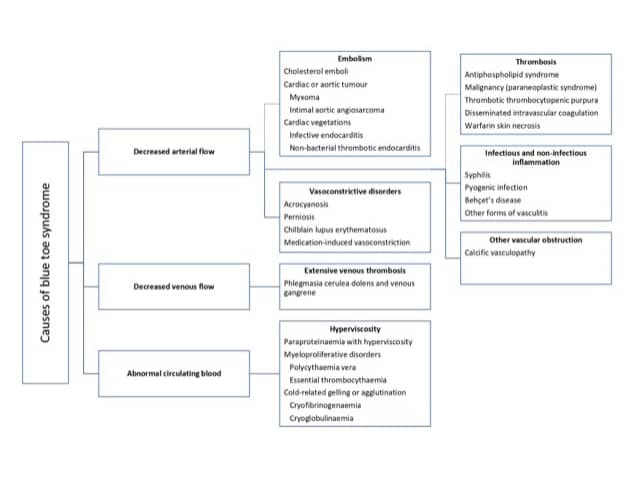

The characteristic blue discolouration and pain in blue toe syndrome are caused by impaired blood flow to the tissue resulting in ischaemia. The impairment of blood flow is due to one or more of the following factors:

These are not mutually exclusive. For example, abnormal circulating blood can induce vasculitis and subsequent thrombosis of the arterioles and capillaries supplying blood to the toes, resulting in a decreased arterial flow.

Adapted from Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009

The blockage or narrowing of arteries by the small clots that lead to blue toe syndrome can result from a number of different conditions.

Occlusion can also be due to syphilis, pyogenic infection (sepsis), Behçet disease, and other forms of vasculitis [1,4].

Narrowed blood vessels can be due to calcific vasculopathy (calciphylaxis) [5].

Abnormal venous drainage associated with extensive venous thrombosis results in phlegmasia cerulea dolens (a painful form of blue toe syndrome associated with leg oedema). Many patients have predisposing factors for venous thrombosis, including:

Blue toe syndrome can be due to abnormal blood constituents. See the DermNet page on Skin conditions of haematological disorders.

The clinical features of blue toe syndrome can range from an isolated blue and painful toe to a diffuse multi-organ system disease that can mimic other systemic illnesses. Any organ or tissue can be affected, although the skin and skeletal muscles of the lower extremities are almost always involved [8].

Cutaneous abnormalities are usually one of the earliest symptoms; most commonly, blue or purple discolouration of the affected toes [9]. Discolouration may affect one foot or both, depending on the underlying pathophysiology. It is often painful and may be associated with claudication.

In a series of 223 patients with cholesterol embolisation, the most frequent cutaneous findings were:

Livedo reticularis may be non-blanching or blanching when the discolouration disappears with pressure and/or fades with leg elevation [10]. Blanching occurs in the first stages of blue toe syndrome, as the sluggish flow of desaturated blood results in the temporary obstruction of blood flow [1].

Mild forms of blue toe syndrome have a good prognosis and subside without sequelae [1]. However, cholesterol fragments blocking blood vessels to other organs can lead to multi-organ disorder [1]. Involvement of the kidneys has a poor prognosis.

Patients with untreated blue toe syndrome from embolisation can suffer from further emboli in the subsequent weeks, resulting in substantial occlusion and the ischaemic loss of digits, the forefoot, and the limb (dry gangrene), necessitating amputation [6].

Blue toe syndrome is a clinical diagnosis based on patient history and findings on examination. It is important to determine the underlying cause of blue toe syndrome to guide treatment [1]. There are usually clues from the clinical assessment, but to confirm the diagnosis, investigation in the form of laboratory blood works, tissue biopsies, and radiological imaging is required.

History and examination should focus on:

A full blood count including a white cell differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein may indicate elevated inflammatory markers. These are often non-specific in blue toe syndrome and can occur with cholesterol emboli as well as numerous other inflammatory driven processes. The blood count and peripheral blood film can help diagnose bone marrow or autoimmune diseases. Liver and renal functions should also be checked.

Other more specific blood tests may include:

Imaging may include:

A definitive diagnosis is usually made by the histopathological confirmation of a biopsy of the affected skin or other involved tissues [13]. Biopsies in patients with a poor peripheral vascular supply should be performed with caution as poor healing is likely at the sampling site. The histopathological findings for cholesterol emboli show intravascular cholesterol crystals, which may be associated with macrophages, giant cells, and eosinophils [13].

The principles of treatment revolve around addressing the cause of the blue toe syndrome. This is usually in the form of relieving occlusion and restoring arterial or venous vessel continuity [6].

Risk factors should be addressed in patients with advanced atherosclerotic disease, including:

Patients with stenotic lesions should be followed up carefully, as the progression of the atheromatous disease will result in a strong likelihood of repetition of the blue toe syndrome [6].