Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Hereditary angioedema — extra information

Hereditary angioedema

Author: Dr Hilary Brown, General Practitioner, Newcastle, NSW, Australia. DermNet Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell/Maria McGivern. August 2019.

Introduction Demographics Causes Classification Clinical features Complications Diagnosis Differential diagnoses Treatment Outcome

What is hereditary angioedema?

Hereditary angioedema is a familial disease characterised by recurrent attacks of self-limiting oedema. It can affect the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and airways.

Who gets hereditary angioedema?

Hereditary angioedema is an autosomal-dominant condition, meaning if one parent has the abnormal gene that codes for angioedema, half of their children will inherit the condition. Around 25% of cases are due to spontaneous mutations.

The prevalence of hereditary angioedema is estimated at 1 in 50,000 persons. There is no particular prevalence amongst ethnic groups or between sexes.

What causes hereditary angioedema?

The gene coding for C1-INH is located on chromosome 11 and nearly 200 mutations of this gene have been described.

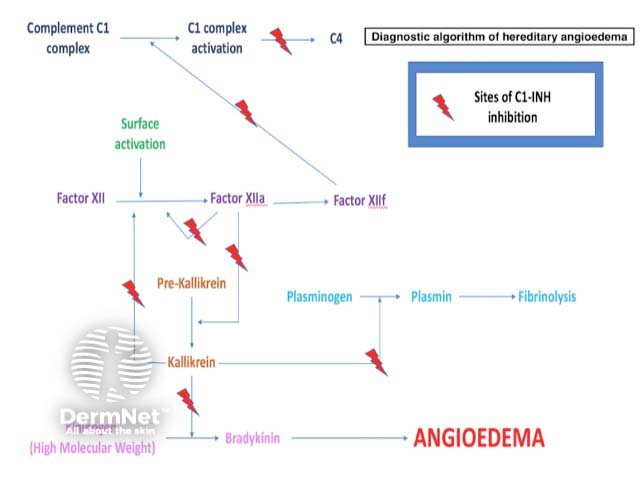

The most common type of hereditary angioedema is associated with a deficiency of functional C1-esterase inhibitor (C1-INH), a serine protease inhibitor that regulates the activation of the classic complement pathway and suppresses spontaneous activation of complement component C1 (figure 1).

C1-INH also regulates the contact (kallikrein-kinin) system, which is responsible for inflammation and blood coagulation. It involves factor XII, factor XIIa, kallikrein, and high-molecular-weight kininogen. The activation of these molecules generates bradykinin, a peptide which promotes inflammation. A deficiency of functional C1-INH results in excessive bradykinin.

Bradykinin can increase vascular permeability by binding to its receptor on vascular endothelial cells, causing angioedema.

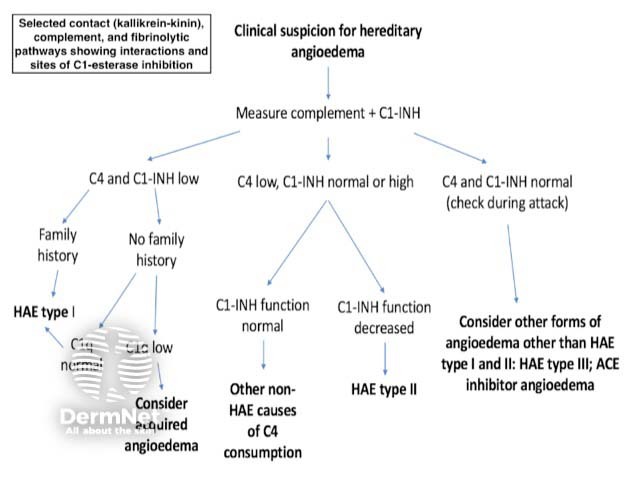

Figure 1. Clinical suspicion for hereditary angioedema

Clinical suspicion for hereditary angioedema

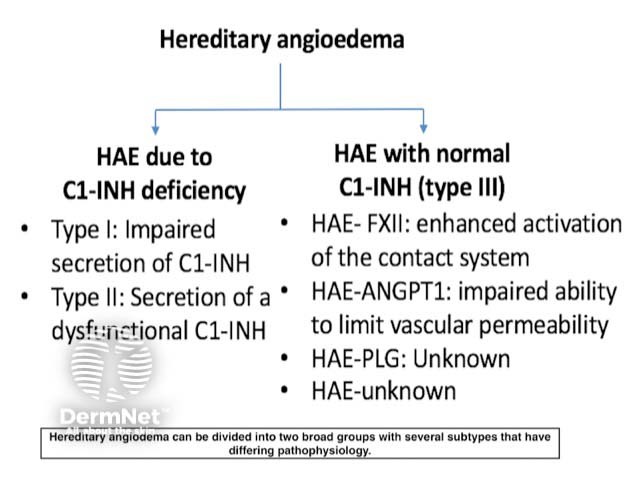

What is the classification of hereditary angioedema?

Hereditary angioedema is classified into three types based on pathogenesis (figure 2).

Type I

- Type I hereditary angioedema shows reduced secretion and low circulating levels of C1-INH.

- Type I hereditary angioedema comprises 80–85% of all cases of hereditary angioedema.

Type II

- Type II hereditary angioedema has either normal or sometimes high levels of C1-INH, but the C1-INH is dysfunctional.

- Type II hereditary angioedema comprises 15–20% of all cases of hereditary angioedema.

Type III

- Type III hereditary angioedema shows a similar clinical picture to type I and II but has normal levels of functional C1-INH.

- Type III hereditary angioedema is caused by at least three known gene mutations, including a mutation of the F12 gene, which codes for factor XII to activation by plasmin.

Figure 2. The types of hereditary angioedema

Types of hereditary angioedema

What are the clinical features of hereditary angioedema?

Symptoms of hereditary angioedema typically begin in childhood, worsen in puberty, and persist throughout life.

Untreated patients have attacks every 7–14 days on average, with a range from every 3 days to almost never.

One-third of patients with hereditary angioedema experience early symptoms of erythema marginatum that may be confused for urticaria. Erythema marginatum is a non-pruritic form of annular erythema more commonly associated with rheumatic fever. The lesions can be static or extend peripherally in a centrifugal way.

The angioedema generally increases over the first 24 hours and then subsides over the next 2–5 days. Oedema may affect an arm, leg, hand, foot, or the abdomen. Oropharyngeal swelling is less common. One or all of these areas can be affected in an attack and it may be asymmetrical.

Stress and trauma, including surgery, can be triggers for episodes, but most episodes of hereditary angioedema are spontaneous.

What are the complications of hereditary angioedema?

An abdominal attack of hereditary angioedema can cause severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting; it is often mistaken for an 'acute abdomen'. Bowel sounds may be absent, and guarding (muscle spasms) may be present on examination. Therefore, many patients with hereditary angioedema undergo unnecessary abdominal surgery, especially prior to the diagnosis of hereditary angioedema.

Laryngeal oedema can be fatal. Historical data reports asphyxiation and death occurring in over 30% of patients with hereditary angioedema without treatment.

Angioedema symptoms are often disabling and disfiguring. Patients may suffer from depression, anxiety, impaired function, and reduced quality of life.

How is hereditary angioedema diagnosed?

Hereditary angioedema is a rare disease and it is therefore encountered infrequently by physicians. This may lead to a delay in diagnosis. The clinician should consider a diagnosis of hereditary angioedema in patients with recurrent attacks of angioedema in the absence of urticaria.

Investigations should include complement levels (figure 3).

- Most patients with hereditary angioedema have low C4 levels with normal C1 and C3 levels.

- Occasionally C4 may be normal between attacks and patients need to be tested during an acute attack.

- If C4 is low, the subsequent measurement of antigenic and functional C1-INH levels confirms the diagnosis and distinguishes between type I and type II hereditary angioedema.

- If C4 and C1-INH levels are normal, consider type III hereditary angioedema. A factor XII mutation may be responsible in 20–25% of these cases or another mutation may be responsible.

Figure 3. Sites of C1-esterase inhibition

Sites of C1-esterase inhibition

What is the differential diagnosis for hereditary angioedema?

The main differential diagnoses for hereditary angioedema are:

- Acquired angioedema

- Acute allergic urticaria and angioedema associated with type I hypersensitivity and allergy

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor-induced angioedema

- Chronic spontaneous urticaria with angioedema

- Other conditions such as facial cellulitis, dermatomyositis, Crohn skin disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

Acquired angioedema

Acquired angioedema results from a lymphoproliferative disorder such as a B-cell lymphoma (type I) or from the development of mainly immunoglobulin G antibodies against C1-INH (type II). C1q measurement can help to distinguish acquired angioedema from hereditary angioedema. C1q levels are normal in hereditary angioedema but low in acquired angioedema, which otherwise has a similar C1-INH/C4 profile.

Acute allergic angioedema

Acute allergic angioedema occurs in response to a known trigger that provokes an associated histamine response with urticaria and pruritus. Antihistamines are helpful in this condition where they afford no benefit in hereditary angioedema. On investigation, serum complement levels are normal as opposed to low in hereditary angioedema.

ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema

ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema occurs because the inhibition of ACE allows bradykinin to accumulate. Serum complement levels are normal.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria with angioedema

Chronic spontaneous urticaria with angioedema is classified as an autoimmune disorder. Serum complement levels are normal.

What is the treatment for hereditary angioedema?

Patients with hereditary angioedema should be counselled to avoid agents that may precipitate attacks such as an ACE inhibitor or oestrogen. Stress is thought to be a trigger for attacks, so stress reduction or management may also be advised.

Treatment is divided into three areas:

- Long-term prophylaxis

- Short-term prophylaxis (eg, for a surgical procedure)

- Treatment of acute attacks.

Long-term prophylaxis

Long-term prophylaxis is indicated for patients with frequent or severe attacks. The options include:

- An androgen (eg, danazol, stanozolol, methyltestosterone, or oxandrolone)

- An antifibrinolytic (tranexamic acid)

- A plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor (eg, nanofiltered C1-INH or plasma-derived C1-INH)

- A progestin (norethisterone).

Androgens are contraindicated in pregnancy, lactation, cancer, hepatitis, and childhood. Side effects of androgens include virilisation, weight gain, acne, hypertension, and atherosclerosis. The lowest possible dose should be used to control hereditary angioedema to minimise side effects.

The mechanism of action of tranexamic acid in hereditary angioedema is unknown. Side effects included nausea, diarrhoea, myalgia, and thrombosis.

Short-term prophylaxis

Short-term prophylaxis is indicated for patients who are undergoing planned surgical or dental procedures.

Novel targeted therapies such as a plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor, a kallikrein inhibitor (ecallantide), or a BDKRB2 antagonist (icatibant) should be given prior to the procedure if available.

Alternatives are a 5-day course of danazol or tranexamic acid before the procedure.

Treatment of acute attacks

A plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor, a kallikrein inhibitor, or a BDKRB2 antagonist should be administered as soon as possible after an acute attack if available.

- If a targeted therapy is not available, a high-dose androgen or an antifibrinolytic may be used.

- Fresh frozen plasma can be successful, but also has the potential to exacerbate the condition.

- Adrenaline is of modest benefit.

- Antihistamines and systemic corticosteroids are unlikely to be helpful.

Supportive care, including fluid replacement and pain management, should also be implemented.

What is the outcome for hereditary angioedema?

The recent development of novel targeted therapies has led to improved morbidity and mortality for patients with hereditary angioedema.

References

- Sardana N, Craig T. Recent advances in management and treatment of hereditary angioedema. Pediatrics 2011; 128: 1173–80. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-0546. PubMed

- Parish LC. Hereditary angioedema: diagnosis and management — a perspective for the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65: 843–50. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.09.715. PubMed

- Zuraw BL. Clinical practice. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 1027–36. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMcp0803977. PubMed

- Zuraw BL. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor: Four types and counting. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 884–5. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.01.015. PubMed

- Zuraw BL, Christiansen SC. How we manage persons with hereditary angioedema. Br J Haematol 2016; 173: 821–43. DOI: 10.1111/bjh.14059. PubMed

- Bowen T, Cicardi M, Farkas H, et al. 2010 International consensus algorithm for the diagnosis, therapy and management of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2010; 6: 24. DOI: 10.1186/1710-1492-6-24. PubMed

- Riedl M. Hereditary angioedema therapies in the United States: movement toward an international treatment consensus. Clin Ther 2012; 34: 623–30. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.02.003. PubMed

On DermNet

- Urticaria and urticaria-like conditions

- Angioedema

- Vibratory angioedema

- Acute urticaria

- Chronic spontaneous urticaria

Other websites

- HAE UK — UK patient support group for patients with hereditary angioedema

- HAE International — global non-profit network of patient associations dedicated to raising awareness of hereditary angioedema

- HAE Australasia — Australasian patient advocacy organisation that raises awareness of hereditary angioedema

- US Hereditary Angioedema Association — a US non-profit patient advocacy organisation serving patients with hereditary angioedema