Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Autoimmune/autoinflammatory Rashes

Author: Dr Hellen Geros, Hospital Medical Officer (PGY2), Western Health, Melbourne, Australia. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. November 2020.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

Juvenile dermatomyositis is the most common form of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy affecting children and adolescents under the age of 18 years.

Juvenile dermatomyositis can affect all races and both sexes, although there is a marked female predominance of 5:1. Unlike adult-onset dermatomyositis, there does not appear to be any racial predilection. The peak age of onset is 5–10 years (median 7.4 years). One-quarter of patients present before the age of 4 years. It affects 2–4 children per million per year.

Juvenile dermatomyositis is a small-vessel autoimmune vasculopathy in which the immune system attacks blood vessels leading to muscle inflammation. The exact pathogenesis remains unclear; however, the following factors may have a role:

There are very few case reports of drug-induced dermatomyositis in children. Malignancy is not associated with juvenile dermatomyositis, unlike adult-onset disease.

The clinical features of juvenile dermatomyositis are similar to those of adult-onset dermatomyositis, with skin changes often preceding the muscle weakness.

Heliotrope rash of eyelids

Gottron papules over joints

Nailfold changes

Calcinosis is more common in children with dermatomyositis than in adults, affecting up to 40%. It is a dystrophic calcification in muscle, fascia, subcutaneous tissue, or skin presenting 1–3 years after disease onset. Calcinosis cutis over the elbows, knees, trunk, hands, feet, buttocks, and head presents as hard yellow or white nodules with subsequent ulceration. The development of calcinosis is associated with delayed diagnosis and treatment, and severe or prolonged disease activity.

Lipodystrophy may be localised, partial, or widespread, and affects 10% of juvenile dermatomyositis patients, particularly those with a chronic continuous course; lipodystrophy is rare in adult-onset dermatomyositis. The onset is often delayed; in one large study of 28 patients, lipodystrophy began 4.6 years after diagnosis of juvenile dermatomyositis. Joint contractures and calcinosis cutis were found to be strong predictors for the development of lipodystrophy. As the development of lipodystrophy is associated with diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance, hypertriglyceridaemia, and non-alcoholic steatotic hepatitis, careful monitoring is required in these patients.

Arthritis, either primary joint disease or secondary to the muscle weakness, is common.

Interstitial lung disease, cardiac disease, and liver/bowel involvement are rare but serious complications of juvenile dermatomyositis.

Calcinosis cutis

Diagnosis of juvenile dermatomyositis is suspected clinically in a child presenting with the classic skin signs of heliotrope rash, Gottron papules/sign, and myositis (Bohan Peters diagnostic criteria).

Investigations, which may include some of the following, will confirm the diagnosis and assist in predicting prognosis.

Skin signs without myositis:

Muscle weakness and/or myositis without skin changes:

The aim of treatment in juvenile dermatomyositis is to control disease activity and induce remission, prevent long term organ damage and deformity, and improve function and quality of life. It generally requires a multidisciplinary team including a general practitioner, physiotherapist, dermatologist, and paediatric rheumatologist.

Initial treatment requires high dose systemic corticosteroids to rapidly reduce skin and muscle inflammation. The addition of steroid-sparing agents, such as methotrexate or ciclosporin, is more effective than prednisone alone, and allows the corticosteroid dose to be weaned quickly, minimising side effects associated with long term/high dose use. Rituximab has been reported to improve some cutaneous features and myositis in juvenile dermatomyositis; calcinosis, alopecia, poikiloderma, and lipodystrophy showed no major improvements in a large trial of 48 patients. No treatment has been found to consistently improve the calcinosis.

The prognosis for juvenile dermatomyositis has markedly improved since the early use of high dose steroids has become the standard of care.

The disease course in one-third is monocyclic (treatment ceased within 2 years with longterm remission), one-quarter is polycyclic (treatment required again after a remission), and the remainder follow a chronic course unable to cease treatment.

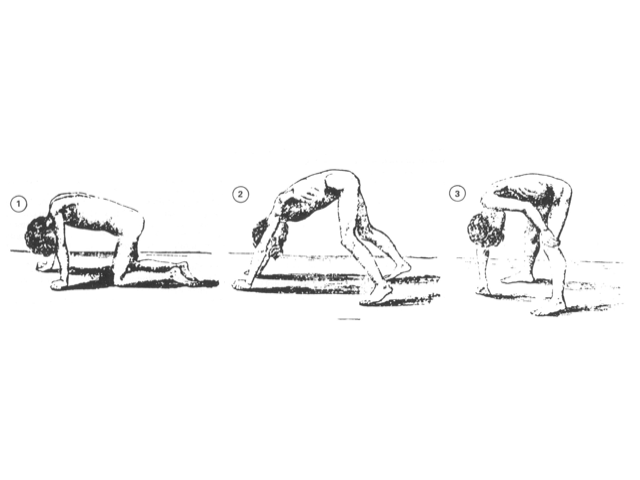

With adequate treatment some children lead normal lives with full recovery. However, a significant proportion have a prolonged course with residual muscle weakness and atrophy, joint contractures, and calcinosis. Irreversible muscle damage and calcinosis cutis can significantly impact physical function and quality of life, necessitating assistance with self-care or being unable to walk unassisted.

The mortality rate is 2–3%, with death due to pulmonary, gastrointestinal, cardiac, and multisystem failure.