Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Stevens–Johnson syndrome / toxic epidermal necrolysis — extra information

Stevens–Johnson syndrome / toxic epidermal necrolysis

Author: Vanessa Ngan, Staff Writer; Dr Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand, 2003. Updated by Dr Delwyn Dyall-Smith, 2009. Further updated by Dr Amanda Oakley, January 2016.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Prevention

Outlook

What are Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis?

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are now believed to be variants of the same condition, distinct from erythema multiforme. SJS/TEN is a rare, acute, serious, and potentially fatal skin reaction in which there are sheet-like skin and mucosal loss. Using current definitions, it is nearly always caused by medications.

Who gets SJS/TEN?

SJS/TEN is a very rare complication of medication use (estimated at 1–2/million each year for SJS, and 0.4–1.2/million each year for TEN).

- Anyone on medication can develop SJS/TEN unpredictably.

- It can affect all age groups and all races.

- It is slightly more common in females than in males.

- It is 100 times more common in association with human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV).

Genetic factors are important.

- There are HLA associations in some races to anticonvulsants and allopurinol.

- Polymorphisms to specific genes have been detected (eg, CYP2C coding for cytochrome P450 in patients reacting to anticonvulsants).

More than 200 medications have been reported in association with SJS/TEN.

- It is more often seen with drugs with long half-lives compared to even a chemically similar related drug with a short half-life. A half-life of a medication is the time that half of the delivered dose remains circulating in the body.

- The medications are usually systemic (taken by mouth or injection), but TEN has been reported after topical use.

- No drug is implicated in about 20% of cases

- SJS/TEN has rarely been associated with vaccination and infections such as mycoplasma and cytomegalovirus. Infections are generally associated with mucosal involvement and less severe cutaneous disease than when drugs are the cause.

The drugs that most commonly cause SJS/TEN are antibiotics in 40%. Other drugs include:

- Sulfonamides: cotrimoxazole

- Beta-lactam: penicillins, cephalosporins

- Anti-convulsants: lamotrigine, carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbitone

- Allopurinol

- Paracetamol/acetaminophen

- Nevirapine (non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor)

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (oxicam type mainly)

- The anticancer drugs, PD-1 inhibitors.

What causes SJS/TEN?

SJS/TEN is a rare and unpredictable reaction to a medication. The mechanism has still not been understood and is complex.

Drug-specific CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes can be detected in the early blister fluid. They have some natural killer cell activity and can probably kill keratinocytes by direct contact. Cytokines implicated include perforin/granzyme, granulysin, Fas-L and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα).

There are probably two major pathways involved:

- Fas-Fas ligand pathway of apoptosis has been considered a pivotal step in the pathogenesis of TEN. The Fas ligand (FasL), a form of tumour necrosis factor, is secreted by blood lymphocytes and can bind to the Fas ‘death’ receptor expressed by keratinocytes.

- Granule-mediated exocytosis via perforin and granzyme B resulting in cytotoxicity (cell death). Perforin and granzyme B can be detected in early blister fluid, and it has been suggested that levels may be associated with disease severity.

What are the clinical features of SJS/TEN?

SJS/TEN usually develops within the first week of antibiotic therapy but up to 2 months after starting an anticonvulsant. For most drugs, the onset is within a few days up to 1 month.

Before the rash appears, there is usually a prodromal illness of several days duration resembling an upper respiratory tract infection or 'flu-like illness. Symptoms may include:

- Fever > 39 C

- Sore throat, difficulty swallowing

- Runny nose and cough

- Sore red eyes, conjunctivitis

- General aches and pains.

There is then an abrupt onset of a tender/painful red skin rash starting on the trunk and extending rapidly over hours to days onto the face and limbs (but rarely affecting the scalp, palms or soles). The maximum extent is usually reached by four days.

The skin lesions may be:

- Macules — flat, red and diffuse (measles-like spots) or purple (purpuric) spots

- Diffuse erythema

- Targetoid — as in erythema multiforme

- Blisters — flaccid (ie, not tense).

The blisters then merge to form sheets of skin detachment, exposing red, oozing dermis. The Nikolsky sign is positive in areas of skin redness. This means that blisters and erosions appear when the skin is rubbed gently.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Mucosal involvement is prominent and severe, although not forming actual blisters. At least two mucosal surfaces are affected including:

- Eyes (conjunctivitis, less often corneal ulceration, anterior uveitis, panophthalmitis) — red, sore, sticky, photosensitive eyes

- Lips/mouth (cheilitis, stomatitis) — red crusted lips, painful mouth ulcers

- Pharynx, oesophagus — causing difficulty eating

- Genital area and urinary tract — erosions, ulcers, urinary retention

- Upper respiratory tract (trachea and bronchi) — cough and respiratory distress

- Gastrointestinal tract — diarrhoea.

The patient is very ill, extremely anxious and in considerable pain. In addition to skin/mucosal involvement, other organs may be affected including liver, kidneys, lungs, bone marrow and joints.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Stevens Johnson Syndrome

Stevens Johnson Syndrome

What are the complications of SJS/TEN?

SJS/TEN can be fatal due to complications in the acute phase. The mortality rate is up to 10% for SJS and at least 30% for TEN.

During the acute phase, potentially fatal complications include:

- Dehydration and acute malnutrition

- Infection of skin, mucous membranes, lungs (pneumonia), septicaemia (blood poisoning) with bacteria and Candida

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Gastrointestinal ulceration, perforation and intussusception

- Shock and multiple organ failure including kidney failure

- Thromboembolism and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.

How is SJS/TEN diagnosed?

SJS/TEN is suspected clinically and classified based on the skin surface area detached at maximum extent.

SJS

- Skin detachment < 10% of body surface area (BSA)

- Widespread erythematous or purpuric macules or flat atypical targets

Overlap SJS/TEN

- Detachment between 10% and 30% of BSA

- Widespread purpuric macules or flat atypical targets

TEN with spots

- Detachment > 30% of BSA

- Widespread purpuric macules or flat atypical targets

TEN without spots

- Detachment of > 10% of BSA

- Large epidermal sheets and no purpuric macules

The category cannot always be defined with certainty on initial presentation. The diagnosis may, therefore, change during the first few days in the hospital.

Investigations in SJS/TEN

If the test is available, elevated levels of serum granulysin taken in the first few days of a drug eruption may be predictive of SJS/TEN.

Skin biopsy is usually required to confirm the clinical diagnosis and to exclude staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) and other generalised rashes with blisters

The histopathology shows keratinocyte necrosis (death of individual skin cells), full thickness epidermal/epithelial necrosis (death of an entire layer of skin), minimal inflammation (very mild lymphocytic infiltrate of the superficial dermis). The direct immunofluorescence test on the skin biopsy is negative, indicating the disease is not due to deposition of antibodies in the skin.

Blood tests do not help to make the diagnosis but are essential to make sure fluid and vital nutrients have been replaced, to identify complications and to assess prognostic factors (see below). Abnormalities may include:

- Anaemia occurs in virtually all cases (reduced haemoglobin).

- Leucopenia (reduced white cells), especially lymphopenia (reduced lymphocytes) is very common (90%).

- Neutropenia (reduced neutrophils), if present, is a bad prognostic sign.

- Eosinophilia (raised eosinophil count) and atypical lymphocytosis (odd-looking lymphocytes) do not occur.

- Mildly raised liver enzymes are common (30%), and approximately 10% develop overt hepatitis.

- Mild proteinuria (protein leaking into the urine) occurs in about 50%. Some changes in kidney function occur in the majority.

In vitro diagnostic tests for drug allergies including SJS/TEN are under investigation.

Patch testing rarely identifies the culprit in SJS/TEN, and is not recommended.

SCORTEN

SCORTEN is an illness severity score that has been developed to predict mortality in SJS and TEN cases. One point is scored for each of the seven criteria present at the time of admission. The SCORTEN criteria are:

- Age > 40 years

- Presence of malignancy (cancer)

- Heart rate > 120

- Initial percentage of epidermal detachment > 10%

- Serum urea level > 10 mmol/L

- Serum glucose level > 14 mmol/L

- Serum bicarbonate level < 20 mmol/L.

The risk of dying from SJS/TEN depends on the score.

- SCORTEN 0-1 > 3.2%

- SCORTEN 2 > 12.1%

- SCORTEN 3 > 35.3%

- SCORTEN 4 > 58.3%

- SCORTEN 5 or more > 90%

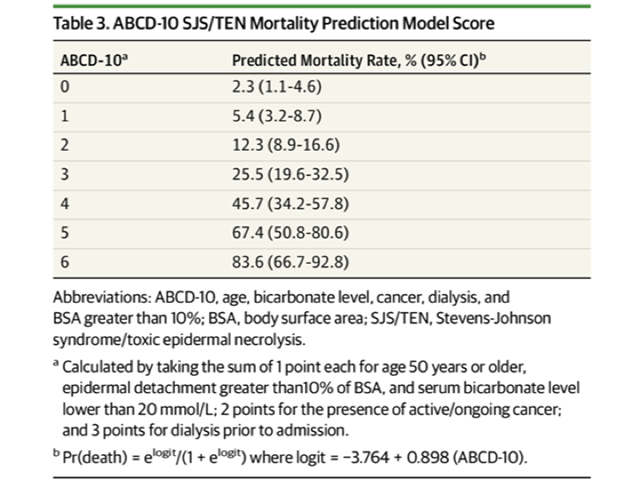

In 2019, a new prediction model was proposed, the ABCD-10.

A: age over 50 years (one point)

B: bicarbonate level < 20 mmol/L (one point)

C: cancer present and active (two points)

D: dialysis prior to admission (3 points)

10: epidermal detachment ≥ 10% body surface area on admission (one point)

The ABCD-10 was evaluated in a cohort of 370 patients >with SJS/TEN in multiple institutions in the USA and predicted in-hospital mortality as well as SCORTEN. The predicted mortality rates in this cohort are shown in the table.

ABCD 10 Mortality prediction model score

Validation in other populations is required.

What is the differential diagnosis of SJS/TEN?

In the differential diagnosis of SJS/TEN consider:

- Other severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) to drugs (eg, drug hypersensitivity syndrome)

- Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and toxic shock syndrome

- Erythema multiforme, particularly erythema multiforme major (with mucosal involvement)

- Mycoplasma infections

- Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus.

What is the treatment for SJS/TEN?

For further details, see Stevens Johnson syndrome / toxic epidermal necrolysis: nursing management.

Care of a patient with SJS/TEN requires:

- Cessation of suspected causative drug(s) — the patient is less likely to die, and complications are less if the culprit drug is on or before the day that blisters/erosions appear

- Hospital admission — preferably immediately to an intensive care and burns unit with specialist nursing care, as this improves survival, reduces infection and shortens hospital stay

- Consider fluidised air bed

- Nutritional and fluid replacement (crystalloid) by intravenous and nasogastric routes — reviewed and adjusted daily

- Temperature maintenance — as body temperature regulation is impaired, the patient should be in a warm room (30–32C)

- Pain relief — as pain can be extreme

- Sterile handling and reverse isolation procedures.

Skin care

- Examine daily for the extent of detachment and infection (take swabs for bacterial culture).

- Topical antiseptics can be used (eg, silver nitrate, chlorhexidine [but not silver sulfadiazine as it is a sulfa drug])

- Dressings such as gauze with petrolatum, non-adherent nanocrystalline-containing silver gauze or biosynthetic skin substitutes such as Biobrane® can reduce pain.

- Avoid using adhesive tapes and unnecessary removal of dead skin; leave the blister roof as a ‘biological dressing’.

Eye care

- Daily assessment by an ophthalmologist

- Frequent eye drops/ointments (antiseptics, antibiotic, corticosteroid)

Mouth care

- Mouthwashes

- Topical oral anaesthetic

Genital care

- If ulcerated, prevent vaginal adhesions using intravaginal steroid ointment, soft vaginal dilators.

Lung care

- Consider aerosols, bronchial aspiration, physiotherapy

- May require intubation and mechanical ventilation if trachea and bronchi are involved

Urinary care

- Catheter because of genital involvement and immobility

- Culture urine for bacterial infection

General

- Psychiatric support for extreme anxiety and emotional lability

- Physiotherapy to maintain joint movement and reduce the risk of pneumonia

- Regular assessment for staphylococcal or gram negative infection

- The appropriate antibiotic should be given if an infection develops; prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended and may even increase the risk of sepsis

- Consider heparin to prevent thromboembolism (blood clots).

The role of systemic corticosteroids (cortisone) remains controversial. Some clinicians prescribe high doses of corticosteroids for a short time at the start of the reaction, usually prednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day for 3–5 days. However concerns have been raised that they may increase the risk of infection, impair wound healing and other complications, and they have not been proven to have any benefit. They are not effective later in the course of the illness.

Case reports and small patient series have reported benefit from active adjuvant treatments delivered during the first 24–48 hours of illness. As SJS/TEN is a rare condition, controlled trials of therapies in large numbers of patients are difficult.

Ciclosporin 3–5 mg/kg/day is reported to reduce mortality by 60% compared to patients with similar SCORTEN score on admission that were not treated with ciclosporin. There are contraindications to treatment such as renal impairment.

Other options include:

- Anti-TNFα monoclonal antibodies (eg, infliximab, etanercept)

- Cyclophosphamide

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 2–3 g/kg given over 2–3 days

- Plasmapheresis

- Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (GCS-F).

Thalidomide, trialled because of its anti-TNFα effect, increased mortality, and should not be used.

How can SJS/TEN be prevented?

People who have survived SJS/TEN must be educated to avoid taking the causative drug or structurally related medicines as SJS/TEN may recur. Cross-reactions can occur between:

- The anticonvulsants carbamazepine, phenytoin, lamotrigine and phenobarbital

- Beta-lactam antibiotics penicillin, cephalosporin and carbapenem

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Sulfonamides: sulfamethoxazole, sulfadiazine, sulfapyridine.

In the future, we may be able to predict who is at risk of SJS/TEN using genetic screening.

Allopurinol should be prescribed for good indications (eg, gout with hyperuricaemia) and commenced at a low dose (100 mg/day), as SJS/TEN is more likely at doses > 200 mg/day.

What is the outlook for SJS/TEN?

The acute phase of SJS/TEN lasts 8–12 days.

Repithelialisation of denuded areas takes several weeks and is accompanied by peeling of the less severely affected skin. Survivors of the acute phase have increased on-going mortality especially if aged or sick.

Long-term sequelae include:

- Pigment change — a patchwork of increased and decreased pigmentation

- Skin scarring, especially at sites of pressure or infection

- Loss of nails with permanent scarring (pterygium) and failure to regrow

- Scarred genitalia — phimosis (constricted foreskin which cannot retract) and vaginal adhesions (occluded vagina)

- Joint contractures

- Lung disease — bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, obstructive disorders.

Eye problems can lead to blindness:

- Dry and watery eyes, which may burn and sting when exposed to light

- Conjunctivitis: red, crusted, or ulcerated conjunctiva

- Corneal ulcers, opacities and scarring

- Symblepharon: adhesion of conjunctiva of the eyelid to the eyeball

- Ectropion or entropion: turned-out or turned-in eyelid

- Trichiasis: inverted eyelashes

- Synechiae: iris sticks to the cornea.

It may take weeks to months for symptoms and signs to settle.

Dyspigmentation

Nail shedding

Symblepharon

References

- Carr DR, Houshmand E, Heffernan MP. Approach to the acute, generalized, blistering patient. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2007; 26: 139–46. PubMed.

- Chantelot L, Gaillet A, Botterel F, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, de Prost N. Candidaemia and Candida colonization in patients with epidermal necrolysis: a retrospective case series. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191(5):841–843. PubMed

- Cotliar J. Approach to the patient with a suspected drug eruption. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2007; 26: 147. PubMed

- Meth MJ, Sperber KE. Phenotypic diversity in delayed drug hypersensitivity: An immunologic explanation. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine 2006; 73: 769–76. PubMed.

- Mockenhaupt M. Severe drug-induced skin reactions: clinical pattern, diagnostics and therapy. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 2009; 7: 142–62. PubMed.

- Roujeau J-C. Clinical heterogeneity of drug hypersensitivity. Toxicology 2005; 209: 123–129. PubMed.

- Wolf R, Orion E, Marcos B, Matz H. Life-threatening acute adverse cutaneous drug reactions. Clinics in Dermatology 2005; 23; 171–81. PubMed.

- Wolkenstein P, Chosidow O, Fléchet ML, et al. Patch testing in severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions, including Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Contact Dermatitis. 1996; 35: 234–6. PubMed.

- Fujita Y, Yoshioka N, Abe R, et al. Rapid Immunochromatographic Test for Serum Granulysin Is Useful for the Prediction of Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65: 65–8. PubMed.

- Fernando SL. The management of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Aust J of Dermatol 2012; 53: 165–71. PubMed.

- UpToDate accessed 17 January 2016.

- González-Herrada C, Rodríguez-Martín S, Cachafeiro L et al; PIELenRed Therapeutic Management Working Group. Cyclosporine Use in Epidermal Necrolysis Is Associated with an Important Mortality Reduction: Evidence from Three Different Approaches. J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Oct;137(10):2092–2100. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.05.022. Epub 2017 Jun 17. Review. PubMed PMID: 28634032. PubMed.

- Noe MH, Rosenbach M, Hubbard RA, et al. Development and Validation of a Risk Prediction Model for In-Hospital Mortality Among Patients With Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis—ABCD-10. JAMA Dermatol.Published online March 06, 2019. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5605. Journal

On DermNet

- Triggers of SJS/TEN

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome / toxic epidermal necrolysis: nursing management

- Erythema multiforme

- Drug eruptions

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection

- Allergies explained

- Severe cutaneous adverse reaction

- Blistering skin conditions

- Plasmapheresis for skin disease

- Skin signs of rheumatic disease

Other websites

- DermNet e-lectures [Youtube]

- Medscape