Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Author: Dr Diana Purvis, Dermatology Registrar, Green Lane Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand, 2008. Updated by Hon Assoc Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand, September 2015.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis, or AGEP, is an uncommon pustular drug eruption characterised by superficial pustules.

AGEP is usually classified as a severe cutaneous adverse reaction (SCAR) to a prescribed drug. It is also called toxic pustuloderma.

AGEP has an estimated incidence of 3–5 cases per million population per year. It occurs in males and females, children and adults.

Over 90% of cases of AGEP are provoked by medications, most often beta-lactam antibiotics (eg, penicillins, cephalosporins). Other drugs that may cause AGEP are reported to include:

The onset of AGEP is usually within 2 days of exposure to the responsible medication.

Viral infections (Epstein-Barr virus, enterovirus, adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B virus and others) are common triggers of AGEP in children. Spider bites have also been implicated in some cases. There is suspicion that some herbal medicines may have caused AGEP.

Recent research suggests that AGEP is associated with IL36RN gene mutations. These genetic abnormalities make the patient more susceptible to pustulosis when prescribed certain medications or when exposed to infection. Similar mutations are also found in some patients with other pustular disorders such as generalised pustular psoriasis, palmoplantar pustulosis and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau.

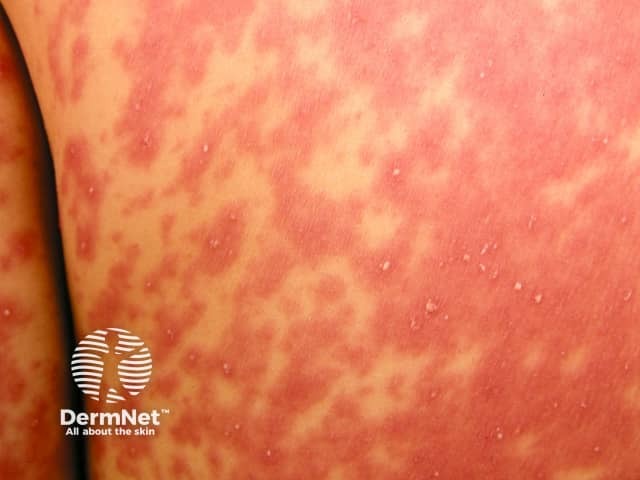

Typically, AGEP starts on the face or in the armpits and groin and then becomes more widespread. It is characterised by the rapid appearance of areas of red skin studded with pinhead-sized sterile pustules. There tends to be more disease in skin folds. Facial swelling often arises.

Oral lesions affect about 20% of patients with AGEP.

AGEP may be associated with a fever and malaise, but often the patient is not particularly unwell. Multiorgan involvement is uncommon but can lead to serious illness.

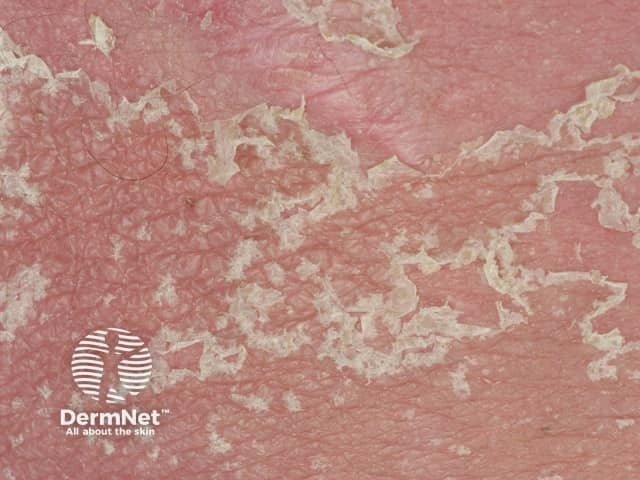

AGEP persists for one to two weeks and then the skin peels off with little collarettes of desquamation as it resolves.

About 10% of patients with AGEP have a severe reaction associated with organ dysfunction (lungs, blood, kidneys, liver).

AGEP can overlap with drug hypersensitivity syndrome or Stevens–Johnson syndrome / toxic epidermal necrolysis, which can be life-threatening.

Secondary infection is uncommon.

AGEP is often diagnosed clinically. Supportive investigations may include:

The skin conditions that may sometimes be difficult to distinguish from AGEP include:

Patients with AGEP are often admitted to the hospital for a few days but patients can be managed at home if they are feeling well enough to eat and drink.

New medicines should be discontinued following the onset of AGEP, particularly antibiotics.

Treatment is then based around relieving symptoms with moisturisers, topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and analgesics until the rash resolves. Systemic therapy is rarely indicated.

The rash of AGEP peels off and resolves spontaneously in about 10 days. It does not usually recur unless the same medication that caused the first episode is taken again. A second episode may be more severe.