Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Cellulitis mimics — extra information

Cellulitis mimics

Author: Dr Jen Taylor, Dermatology Registrar, Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand. DermNet Editor in Chief: Adjunct A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Hamilton, NZ. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell. August 2018.

Introduction - cellulitis

Clinical features

Clinical conditions of cellulitis mimics

What is cellulitis?

Cellulitis is an acute bacterial infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissues of the skin. It is commonly caused by either Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus. Cellulitis presents as an enlarging area of red, hot, swollen, and tender skin. Cellulitis can occur anywhere on the body but is most commonly seen on the lower leg. It may be accompanied by lymphangitis, which appears as a red streak following the lymphatic vessels towards the local lymph node (which may also be tender and enlarged).

Signs of cellulitis are nonspecific and the diagnosis rests largely on the patient's history and physical examination. A number of skin conditions may 'mimic' cellulitis, and around 30% of cases of cellulitis are misdiagnosed. Distinguishing between cellulitis and these mimicking conditions is important to avoid unnecessary treatment and complications, and to expedite appropriate treatment.

What are the clinical features of cellulitis?

Unilateral distribution on the lower leg

Cellulitis of the lower legs is almost always unilateral. Bilateral distribution of cellulitis only rarely occurs, usually as a result of an underlying condition, such as lymphoedema. The bilateral distribution of a rash in the absence of other symptoms of cellulitis should prompt a search for an alternative diagnosis.

Treatment response

If untreated, cellulitis will progress rapidly. If appropriate antibiotics are commenced, the cellulitis should respond within hours to days. A lack of response suggests an alternative diagnosis.

Symptoms and signs of infection

A patient with cellulitis may experience symptoms such as nausea and malaise.

Signs of infection from cellulitis include:

- An intense warm feeling in the area affected

- Fever

- Tachycardia

- Leukocytosis

- Elevated inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]).

Risk factors for infection

There may be a portal of entry, such as an ulcer or injury, that enables bacteria to breach the skin's defences. Other risk factors include chronic oedema, lymphoedema, obesity, and diabetes mellitus.

What are the clinical conditions that commonly mimic cellulitis?

Other cutaneous infections

Other skin infections that share similar features to cellulitis are erysipelas, necrotising fasciitis, and herpes zoster.

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is a superficial variant of cellulitis that is also caused predominantly by S. pyogenes or S. aureus.

Erysipelas presents with:

- Sharply demarcated erythema

- Blistering

- Oedema

- Intense warmth from the affected area

- Systemic symptoms, such as fever, malaise, and nausea.

Necrotising fasciitis

Necrotising fasciitis is a bacterial infection that affects the subcutaneous tissues. As it does not affect the epidermis and upper dermis, its features may be subtle in the early stage, but infection later gives rise to rapid and severe tissue necrosis if untreated. Most patients with necrotising fasciitis are seriously unwell with septic features.

Clues to the diagnosis of necrotising fasciitis include:

- Severe pain, seemingly disproportionate to the clinical findings

- Oedema or tenderness extending beyond the erythematous border of the affected area

- Cutaneous gangrene and blistering

- Crepitus (due to subcutaneous gas produced by anaerobic organisms)

- Fluctuance, indicating purulent material in the soft tissues

- Rapid expansion despite antibiotic therapy.

Necrotising fasciitis

Necrotising fasciitis

Necrotising fasciitis

Herpes zoster

Some of the symptoms of herpes zoster (shingles) are similar to cellulitis, including:

- A sudden onset of fever

- Localised rash with pain

- Swelling

- Heat

- Redness.

However, herpes zoster is characterised by its dermatomal distribution and umbilicated vesicles. Antibiotics are not effective against herpes zoster virus, which is treated with antiviral agents, such as aciclovir.

Herpes zoster

Herpes zoster

Herpes zoster

Venous disease

Venous disease of the lower legs affects around 20% of people aged over 70 years. Damage or degeneration of the leg veins is a very common reason for red legs. Signs of venous insufficiency may include:

- Swelling due to blood pooling

- Colour changes

- Dry, flaking skin

- Firm induration (described as a ‘tethered down’ appearance)

- Swelling of the calves above narrowed ankles (sometimes described as an 'inverted champagne bottle' appearance).

These changes have been classified in a framework of symptoms known as the clinical, aetiological, anatomical and pathophysiological (CEAP) classification.

Dependent rubor

In this condition, dilated skin vessels result in a red, dusky discolouration of the legs when sitting or standing. Patients are typically asymptomatic.

Venous eczema

Prolonged oedema leads to inflammation and subsequent redness, itch, dryness, and scaling and what is referred to as venous eczema. Venous eczema is not usually as red, hot, or oedematous as cellulitis.

Venous eczema

Venous eczema

Venous eczema

Venous thrombosis

Superficial thrombophlebitis causes redness, heat, and tenderness resembling cellulitis, except that the inflammation is linear, following the course of the underlying thrombosed vein, which is palpable and tender. Oedema is absent and the skin is not taut, smooth, or shiny. There are no systemic symptoms.

The inflammation from deep venous thrombosis does not spread to the skin surface nor cause erythema.

Lipodermatosclerosis

Lipodermatosclerosis can be acute or chronic. Acute lipodermatosclerosis is often tender and bright red in colour, and occurs with or without oedema. Systemic symptoms and signs of infection are absent. Later, a reddish-brown discolouration indicates prolonged inflammation and deposition of haemosiderin (an insoluble form of iron that has leaked out of the swollen capillaries).

Chronic lipodermatosclerosis has a ‘tethered down’ appearance due to fibrosis (hardening) of the deeper tissues.

Acute lipodermatosclerosis

Acute lipodermatosclerosis

Chronic lipodermatosclerosis

Dermatitis

Dermatitis, or eczema, describes a group of common inflammatory skin conditions. Leg dermatitis may be due to atopic dermatitis, discoid eczema, contact dermatitis, eczema craquelé (due to dry skin), or venous eczema. Combinations can occur.

Acute eczema

Acute eczema can mimic cellulitis, regardless of the cause; it is characterised by erythema, weeping, crusting, and blistering and may be secondarily infected (impetiginisation).

Acute eczema

Acute eczema

Acute eczema

Contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis is classified as contact irritant dermatitis or contact allergic dermatitis (a type IV hypersensitivity reaction).

Irritants that cause contact dermatitis include soaps and detergents.

Potential allergens that can cause contact dermatitis include:

- Colophony in adhesive bandages

- Rubber accelerants in elastic bandages

- Preservatives in moisturising creams and topical medicaments.

Contact dermatitis presents with blistered or scaly, erythematous plaques, which are often irregular in shape and sharply demarcated. Patients may give a history of exposure to a relevant irritant or allergen. Systemic symptoms and signs are absent.

Contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis

Panniculitis

Panniculitis refers to a group of conditions in which there is subcutaneous inflammation of fat. Panniculitis is characterised by red, firm, tender plaques or nodules that have a predilection for the lower legs.

The most common form of panniculitis is erythema nodosum, which can be distinguished from cellulitis by its bilateral and multifocal distribution, recurrent nature, and absence of oedema. Patients may have systemic symptoms, either from an underlying cause, or from the panniculitis itself, which can cause fever, malaise, and arthralgia.

Lupus panniculitis

Lymphoedema

Lymphoedema is a common mimic of cellulitis. The underlying pathogenesis of lymphoedema is similar to venous disease, in which there is decreased tissue oxygenation as a result of extravasated lymph.

Clinical features of lymphoedema include:

- Long-standing non-pitting oedema with induration

- Erythema

- Hyperkeratosis

- Viral wart-like papules and plaques.

The inguinal lymphatics may have been damaged or occluded by filariasis, lymph node dissection, radiation therapy, or obesity. Infectious signs and symptoms are absent.

Lymphoedema is associated with a risk of cutaneous infection, including cellulitis, due to impaired lymphatic drainage.

Eosinophilic cellulitis

Eosinophilic cellulitis, or Wells syndrome, is characterised by recurrent itchy or painful plaques of unknown cause in which prominent eosinophils are found on skin biopsy. A minority of patients with eosinophilic cellulitis may experience malaise and fevers but multiple lesions and the recurring history should distinguish it from cellulitis. Plaques are usually bright red at first, then fade over 4–8 weeks, leaving green, grey, or brown patches.

Wells syndrome

Wells syndrome

Wells syndrome

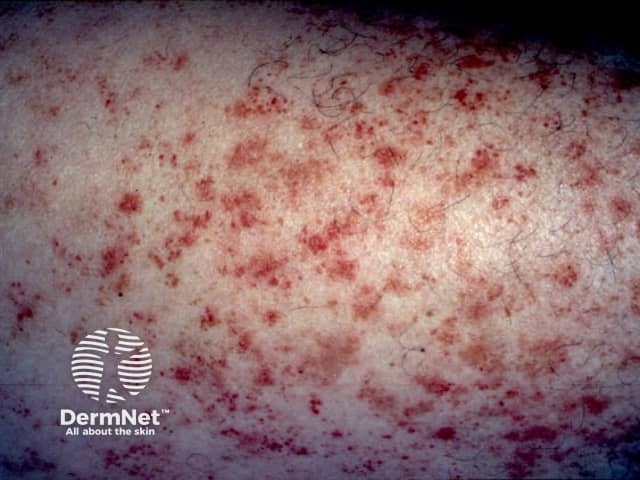

Small vessel vasculitis

Small vessel vasculitis is characterised by painful erythematous plaques and palpable purpura. It most often affects both lower legs. There are various causes.

Vasculitis can be accompanied by ulceration, blistering and mild systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise. Multiple and non-blanching lesions distinguish it from cellulitis. Biopsy will usually show leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Small vessel vasculitis

Small vessel vasculitis

Small vessel vasculitis

Capillaritis

Capillaritis may be unilateral or bilateral, acute, chronic or recurrent. It favours the lower legs. It is characterised by 'cayenne-pepper' petechiae, but these may resemble cellulitis when confluent and accompanied by erythematous patches and oedema. The leg is cool and there are no systemic symptoms.

Other cellulitis mimics

Rare mimics of cellulitis include:

Carcinoma erysipeloides

Erythromelalgia

Periodic fever

References

- Hirschmann J, Raugi G. Lower limb cellulitis and its mimics. Part I. Lower limb cellulitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67: 163.e1–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.03.024. PubMed

- Keller E, Tomecki K, Alraies M. Distinguishing cellulitis from its mimics. Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79: 547–52. DOI: 10.3949/ccjm.79a.11121. PubMed

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J et al (eds). Dermatology, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012.

- Arakaki R, Strazzula L, Woo E, Kroshinsky D. The impact of dermatology consultation on diagnostic accuracy and antibiotic use among patients with suspected cellulitis seen at outpatient internal medicine offices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2014; 150: 1056–61. DOI: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1085. PubMed

- Miteva M, Romanelli P, Kirsner R. Lipodermatosclerosis. Dermatologic Ther 2010; 23: 375–88. DOI: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01338.x. PubMed

- Imadojemu S, Rosenbach M. Dermatologists must take an active role in the diagnosis of cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol 2017; 153: 134. DOI:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4230. Journal

- Nazarko L. The accurate diagnosis and treatment of lipodermatosclerosis. Br J Nurs 2009; 18: 715–18. DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2009.18.12.42883. PubMed

- Salmon M. Differentiating between red legs and cellulitis and reviewing treatment options. Br J Community Nurs 2015; 20; 474–80. DOI: 10.12968/bjcn.2015.20.10.474. PubMed

On DermNet

Other websites

- Medscape:

- Cellulitis — Medline Plus

- Patient information: Skin and soft tissue infection (cellulitis) (Beyond the Basics) — UpToDate (for subscribers)