Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Mycosis fungoides — extra information

Mycosis fungoides

Author: Vanessa Ngan, Staff Writer, 2006

DermNet Update, May 2021. Copy edited by Gus Mitchell.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

Variation in skin types

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

What is mycosis fungoides?

Mycosis fungoides is the commonest type of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, a form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterised clinically by progression from patches to plaques to tumours and, on histology, by an epidermotropic infiltrate of small to medium-sized CD4+ T-cells (lymphocytes).

Patches and plaques of mycosis fungoides

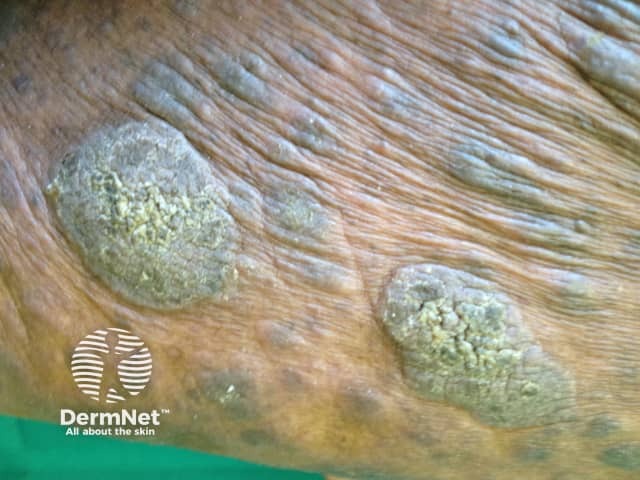

Plaque stage mycosis fungoides

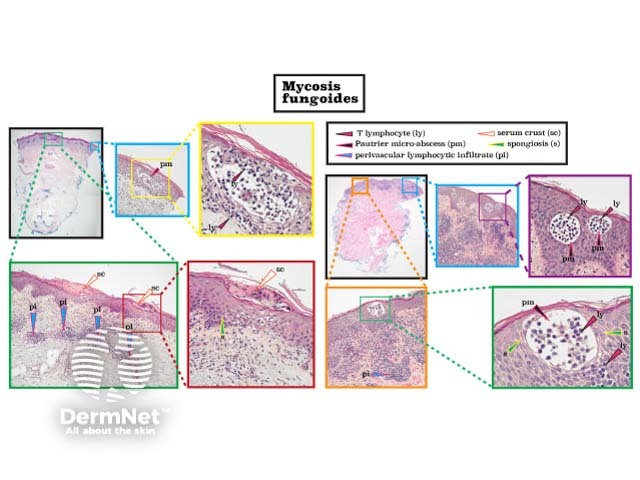

Mycosis fungoides histology

Who gets mycosis fungoides?

Mycosis fungoides (MF) represents 50% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas and 60-70% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL). However, it is an uncommon condition with an estimated incidence worldwide of 6.4 per million.

Onset is usually in late adulthood (median age 55–60 years) with a male predominance (2:1) in white patients. Diagnosis in patients under 30 years of age is highest in Asians, Pacific Islanders, and Black Americans.

What causes mycosis fungoides?

The aetiopathogenesis of mycosis fungoides remains unknown. Theories include chronic antigen stimulation, a genetic predisposition (eg, HLA type), or chemical exposure (eg, medications). Geographical clustering of cases and MF affecting family members suggests environmental triggers. Unlike some forms of CTCL, there is no evidence currently for a viral aetiology.

What are the clinical features of mycosis fungoides?

Mycosis fungoides can present as a chronic itch, even before there are clinical signs of disease. Classic MF progresses slowly over years from patches to plaques and may eventually form tumours. Most patients are diagnosed with early-stage disease.

Patch stage

- Poorly defined, irregular, finely scaling, red patches of variable size often with atrophic (thin, wrinkled) skin

- Occurs mainly on sun-protected sites particularly the lower trunk, thighs and, in women, the breasts

- Often asymptomatic

- Hypopigmented variant: pale, finely scaly patches without atrophy in children and Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI

- Poikiloderma atrophicans vasculare is atrophic patch stage MF presenting with skin thinning, pigment changes, and dilation of capillaries (telangiectasia)

Patch stage mycosis fungoides

Patch stage mycosis fungoides

Patch stage mycosis fungoides

Mycosis fungoides

Plaque stage

- Well-demarcated annular or arciform itchy thickened lesions

- Colour often red, violaceous, or brown, sometimes scaly

- Individual plaques can become quite large with central regression

- May develop from patches or de novo

- Initially involves less than 10% of the body surface area (BSA), becoming widespread later

Plaque stage mycosis fungoides

Plaque stage mycosis fungoides

Plaque stage mycosis fungoides

Tumour stage

- Large irregular lumps (>1 cm) developing from plaques

- Deep red to violaceous colour, often shiny surface

Tumour stage mycosis fungoides

Tumour stage mycosis fungoides

Tumour stage mycosis fungoides

Mycosis fungoides

Non-classic clinical presentations of mycosis fungoides

There are many clinical presentations that do not look like classic mycosis fungoides but follow the same natural history including:

- Syringotropic MF

- Bullous MF

- Solitary MF

- Pustular MF

- Mycosis fungoides palmaris et plantaris

- Forms resembling (amongst others):

Clinical variants defined in the WHO-EORTC classification

- Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (follicular T-cell lymphoma, pilotropic MF, MF-associated mucinosis)

- Most common non-classic variant in adults

- Itchy grouped papules that may resemble keratosis pilaris or acne, plaques, or tumours around hair follicles

- Usually head and neck area

- Often associated with alopecia due to lymphomatous change around hair follicles

- May have associated mucinorrhoea, nail involvement.

- Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease)

- Rare variant

- Solitary slow-growing scaly patch or warty plaque

- Usually located on distal extremities.

- Granulomatous slack skin

- Very rare variant

- Pendulous folds of skin in erythematous plaques

- Axilla and groin are the typical sites involved.

Other clinical presentations of mycosis fungoides

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides

Pagetoid reticulosis

Mycosis fungoides palmaris

Other clinical features of mycosis fungoides

- Epidermal cyst

- Typical ‘B’ symptoms — fever, weight loss.

Mycosis fungoides in children

Mycosis fungoides is the most common primary cutaneous lymphoma (65%) in children but diagnosis is often delayed (2–5 years). The mean age at diagnosis is 10 years, and the sexes are affected almost equally. Most children present with non-classic and often multiple variants. More than 50% of children present with the hypopigmented variant of MF; classic MF affects 40%, and folliculotropic MF in one-third.

How do clinical features vary in differing types of skin?

Mycosis fungoides in skin of colour often presents as hypopigmented papules and plaques without epidermal atrophy. A large case series from Johns Hopkins reported Black American males presented with later stage disease and greater skin involvement than white Americans; Black American females had early-onset aggressive disease. Patients with hypopigmented lesions were more likely to have early-stage disease and better survival than those with advanced-stage disease in another US series.

Dermoscopy of mycosis fungoides

Classic patch stage mycosis fungoides

- Vessels

- Fine short linear

- Spermatozoan vascular structures - highly specific

- Scale - white

- Colour - yellow-orange

- Follicular changes - not seen

Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides

- Polygonal structures - lobules of white storiform streaks and fine red dots or hairpin vessels

- Reticular brown septa - unevenly or intermittently distributed pigmented dots

- Dotted and glomerular vessels

- Red-yellow smudges, pink-white background

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides

- Early change - white perifollicular halos of variable sizes

- Late change - comedo-like openings

Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides

- Short linear spermatozoa-like vessels

- Focal white scale

- Brown-yellow structures

- Broken pigment network

- Whitish background

Erythrodermic mycosis fungoides

- Dotted, linear irregular, and spermatozoan vessels

- Brown structureless areas

- Perifollicular flesh-coloured circles, radial or concentric vessels

- Trichoscopy - also white interfollicular scale, numerous grey dots

What are the complications of mycosis fungoides?

- Ulceration of plaques and tumours, with secondary bacterial infection

- Extracutaneous spread – to lymph nodes and, rarely, internal organs including lungs, nasopharynx, bones, and CNS

- Erythrodermic mycosis fungoides — unlike Sézary syndrome there are no/few circulating ‘Sézary cells’ in the peripheral blood

- Sézary syndrome can sometimes be preceded by mycosis fungoides

- Transformation to large cell lymphoma

- Other forms of lymphoma, skin cancers, and internal malignancies

- Impact on quality of life — anxiety and depression due to uncertainty about disease progression, and the economic burden of chronic disease

How is mycosis fungoides diagnosed?

The diagnosis of mycosis fungoides requires careful clinicopathological correlation. Dermoscopy can help to distinguish MF from inflammatory dermatosis, other causes of erythroderma, and leprosy (see Dermoscopy of leprosy).

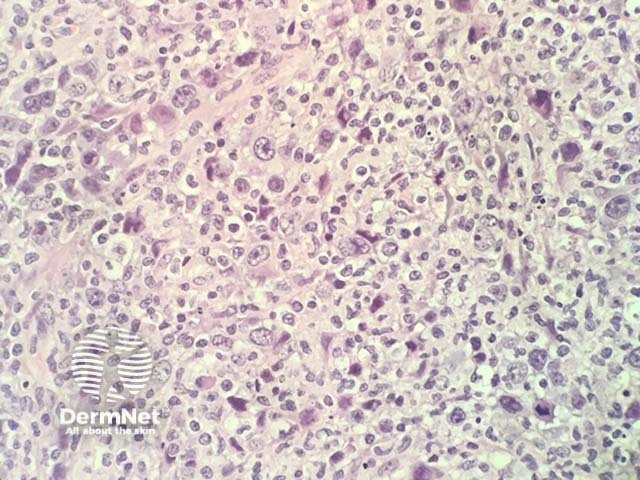

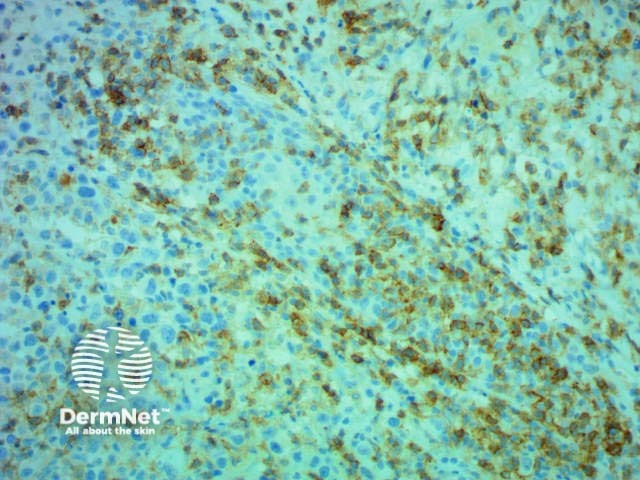

Multiple skin biopsies are often required over time to confirm the diagnosis especially in the early stages. Histopathology is characterised by infiltrates of malignant CD4+ T-cells (see Mycosis fungoides pathology).

Further investigations performed on skin biopsy specimens may include:

- Immunohistochemistry

- Electron microscopy

- In situ hybridisation

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

- Fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH) (see Cytogenetic testing)

- T-cell receptor (TCR) gene studies.

Blood tests, lymph node biopsy, and imaging (eg, CT/PET scans) may be required if there is concern the skin lesions are secondary to a systemic lymphoma, in advanced disease (ie, extracutaneous spread), or for TNMB staging.

Skin staging of mycosis fungoides: T1, limited (<10% BSA) patches/plaques; T2, generalised (>10% BSA) patches/plaques; T3, tumours; T4, erythroderma.

Making the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides

Mycosis fungoides, histology

Immunohistochemistry CD4 stain positive

What is the differential diagnosis for mycosis fungoides?

- Patches — dermatitis, psoriasis, and other inflammatory dermatoses

- Plaques and tumours — malignancies including other cutaneous lymphomas

What is the treatment for mycosis fungoides?

Mycosis fungoides is treatable, not curable. There are no globally accepted treatment guidelines. Treatment should be guided by the patient’s wishes, stage of disease, availability of options, and local expertise. Disease relapse is common after most treatments. A wait-and-see approach can be considered for early limited disease.

Topical treatment

- Topical steroids

- Topical chemotherapy eg, nitrogen mustard, carmustine

- Topical bexarotene

Procedural treatment

- Phototherapy — PUVA, narrowband UVB

- Radiotherapy and whole-body total skin electron beam therapy

- Extracorporeal photopheresis

Systemic treatment

- Chemotherapy — mycosis fungoides is relatively chemoresistant

- Immunotherapy — interferon-alpha

- Oral retinoids and rexinoids (eg, bexarotene)

- Other therapies — including denileukin diftitox, monoclonal antibodies, histone deacetylase inhibitors

Only brentuximab vedotin (for CD30+ MF) and allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant alter the natural history of the disease.

What is the outcome for mycosis fungoides?

Mycosis fungoides typically follows an indolent course over years, with an estimated 5-year survival of 87%. The duration of early-stage disease has been estimated to be approximately 18 years. Although improved survival with MF has been demonstrated, it is likely due to earlier diagnosis rather than advances in therapy.

Individual lesions can sometimes remit spontaneously.

Age, skin stage, and the presence/absence of extracutaneous disease are the major predictors of survival. Skin stage T1 disease (limited patches/plaques) does not alter life-expectancy, although approximately one-third of patients with skin stage T1 disease progress to more advanced stages.

Hypopigmented and poikilodermatous variants have reduced disease progression and better disease-specific survival compared to classic MF while folliculotropic, pustular, and granulomatous MF are considered to be more aggressive variants.

The most common cause of death is non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), which is usually the mycosis fungoides but can be a second NHL, with non-NHL malignancy being the second most common.

Bibliography

- Bontoux C, Badrignans M, Afach S, et al. Pustular mycosis fungoides has a poor outcome: a multicentric clinicopathological and molecular case series. Br J Dermatol. 2024;192(1):125-134. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljae312. Journal

- Dobos G, Pohrt A, Ram-Wolff C, et al. Epidemiology of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 16,953 patients. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(10):2921. doi:10.3390/cancers12102921. Journal

- Elghawy O, Sussman JH, Yang AG, et al. Pembrolizumab in Relapsed or Refractory Mycosis Fungoides or Sézary Syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2025;161(6):656–658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2025.0251. Journal

- Geller S, Lebowitz E, Pulitzer MP, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in African American and black patients with mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: retrospective analysis of 157 patients from a referral cancer center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):430–9. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.073. PubMed

- Kaufman AE, Patel K, Goyal K, et al. Mycosis fungoides: developments in incidence, treatment and survival. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(10):2288-94. doi:10.1111/jdv.16325. PubMed Central

- Lovgren ML, Scarisbrick JJ. Update on skin directed therapies in mycosis fungoides. Chin Clin Oncol. 2019;8(1):7. doi:10.21037/cco.2018.11.03. Journal

- Maguire A, Puelles J, Raboisson P, Chavda R, Gabriel S, Thornton S. Early-stage mycosis fungoides: epidemiology and prognosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(1):adv00013. doi:10.2340/00015555-3367. Journal

- Muñoz-González H, Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Clinicopathologic variants of mycosis fungoides. Variantes clínico-patológicas de micosis fungoide. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108(3):192–208. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2016.08.009. Journal

- Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology, 5th edn. Elsevier, 2020: 1226-36.

- Whittaker SJ, Child F. Cutaneous lymphomas. In: Griffiths C, Barker J, Bleiker T, Chalmers R, Creamer D (eds). Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology, 9th edn. Wiley Blackwell, 2016: 140.4–18.

- Wu JH, Cohen BA, Sweren RJ. Mycosis fungoides in pediatric patients: clinical features, diagnostic challenges, and advances in therapeutic management. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37(1):18–28. doi:10.1111/pde.14026. PubMed

On DermNet

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma images

- Mycosis fungoides palmaris et plantaris

- Mycosis fungoides pathology

Other websites

- Mycosis fungoides — Medscape

- Mycosis fungoides — Medline Plus

- Mycosis fungoides — NORD (National Organization of Rare Disorders)