Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Autoimmune/autoinflammatory Connective tissue diseases

Authors: Dr Amanda Saracino, Dermatologist, Alfred Health and Melbourne Dermatology Clinic, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. Professor Christopher Denton, Consultant Rheumatologist and Professor of Experimental Rheumatology, Centre for Rheumatology and Connective Tissue Diseases, University College London, UK. DermNet Editor-in-Chief A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. January 2018. Updated By Dr Saracino in July 2020.

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Classification

Clinical features

Diagnosis

Monitoring

Treatment

Outcome

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune inflammatory condition. It results in potentially widespread fibrosis and vascular abnormalities, which can affect the skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, heart and kidneys. The skin becomes thickened and hard (sclerotic).

Systemic sclerosis has been subdivided into two main subtypes, according to the distribution of skin involvement.

Limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis was previously referred to as CREST syndrome to denote key features:

The general term ‘scleroderma’ is often used for both morphoea (localised scleroderma) and systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma). Distinguishing these two conditions is very important, as they vary greatly and require different treatment.

Sclerodactyly

Microstomia and telangiectases

Abnormal capillaries on dermoscopy

Systemic sclerosis is rare, with prevalence varying from 30–500 cases per million.

Systemic sclerosis is an autoimmune condition characterised by inflammation, fibrosis and vasculopathy.

The precise underlying mechanisms are complex and remain largely unknown. Genetic susceptibility plus a triggering event result in a cascade of innate and adaptive immunoinflammatory responses.

Systemic sclerosis has been associated with injury, exposure to silica, vinyl chloride monomer, chlorinated solvents, trichloroethylene, welding fumes, aromatic solvents, ketones, bleomycin and possibly other drugs (vitamin K, cocaine, penicillamine, appetite suppressants and some chemotherapeutic agents).

A number of pathways are likely involved in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis, including cytokines that injure blood vessels, growth factors that stimulate collagen production, integrin signalling, morphogen pathways, co-stimulatory pathways and more.

Two-thirds of patients with systemic sclerosis have dcSSc: skin involvement is widespread and includes proximal limbs. DcSSC is often rapidly progressive, with significant internal organ involvement.

One-third of patients with systemic sclerosis have lcSSc: sclerosis is limited to the digits, distal limbs (not spreading more proximal than the elbows or knees) and face. LcSSc progresses more slowly than dcSSc and with less internal organ involvement except there is a risk of pulmonary artery hypertension, especially later in the disease course.

Up to 20% of patients with systemic sclerosis have an overlap syndrome with another connective tissue disease and develop arthritis, lupus or myositis.

Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma is a rare subtype without skin sclerosis. These patients have SSc-related internal organ manifestations, Raynaud phenomenon and SSc-specific auto-antibodies.

Different autoantibody profiles are associated with particular clinical features and prognosis, particularly the pattern of antinuclear antibody (ANA) reactivity. Genetic associations in systemic sclerosis can also be mapped to particular ANA subtypes.

Centromere (kinetochore) ANA pattern

Pm-Scl (nucleolar) ANA pattern

U1RNP (speckled) ANA pattern

Th-To (nucleolar) ANA pattern

Topoisomerase-1 / Scl-70 (speckled) ANA pattern

RNA polymerase (P) III (fine speckled, nucleolar) ANA pattern

Fibrillarin / U3RNP (nucleolar)

The clinical features of systemic sclerosis are related to underlying vascular, inflammatory and fibrotic disease. Constitutional symptoms are common, such as fatigue, arthralgia and myalgia.

Skin sclerosis

Hands

Face

Other

Rarer cutaneous features

Puffy hand

Salt and pepper pigmentation

Digital ulcers

Ulcers on foot

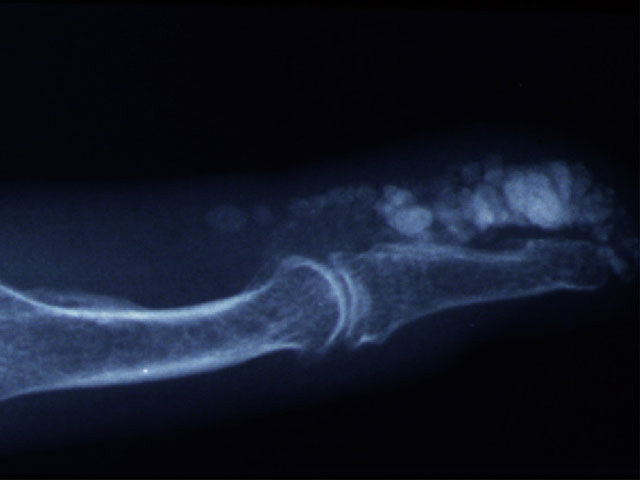

Digital calcinosis

X-ray of calcinosis

Upper GIT

Lower GIT

Scleroderma renal crisis:

Malignancy in association with systemic sclerosis is rare.

The diagnosis of systemic sclerosis is confirmed when key features are present.

Investigations may include:

The joint American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) classification criteria (2013) are utilised to diagnose SSc. A score of 9 or more confirms the diagnosis.

Monitoring of progress and treatment response is vital in systemic sclerosis.

The skin is usually monitored clinically using the modified Rodnan Skin Score (mRSS), which gives an indication of the extent and severity of cutaneous sclerosis, which also reflects the severity and risk of internal organ involvement.

Interlabial distance (mouth opening) can also be measured

Routine annual screening for interstitial lung disease and pulmonary artery hypertension should include:

The DETECT score is a screening tool for pulmonary artery hypertension that uses pulmonary function tests (FVC and DLCO), serum urate, serum NTproBNP and other features to provide a predictive score. A right heart catheter may be indicated in some.

Treatments help with symptoms and may modify the disease outcome, especially early in the disease course. They focus on suppressing inflammation and dilating abnormal / constricted blood vessels. Some newer treatments target specific immunological pathways and signalling molecules.

Fatigue, weakness and generalised musculoskeletal symptoms can be debilitating.

Topical therapies

Physical therapies

Systemic therapies

Vasodilation

General measures such as keeping warm, stretching exercises for joints to reduce the risk of worsening contractures and microstomia, and specifically-related physiotherapy can all be beneficial.

Avoid triggers (smoking cessation, protect from cold)

Natural therapies (unproven)

Medical therapies

Digital ulcers

Cutaneous calcinosis in SSc is notoriously challenging to treat and controlled trials are lacking. It is difficult to manage, and there is poor evidence for therapies listed below.

Pruritus

Pruritus affects up to 43% of those with SSc. Ultimately, pruritus is a sign of active disease and so the SSc itself needs to be treated. Pruritus has been linked to more severe skin and gastrointestinal tract involvement. However, symptom management may also be needed and can include:

Facial fat loss

Interstitial lung disease

Pulmonary artery hypertension

Renal disease

Gastrointestinal tract

There is no cure for systemic sclerosis. Survival is determined by the disease subset and internal organ manifestations. Interstitial lung disease and pulmonary artery hypertension account for almost two-thirds of deaths related to systemic sclerosis.

Proactive and routine annual screening allows early intervention with disease-modifying drugs. These have led to an improvement in prognosis and long term outcomes in recent years.;