Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Melanoma in skin of colour — extra information

Melanoma in skin of colour

Author: Rajan Ramji, Final Year Medical Student, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. DermNet New Zealand Editor in Chief: Hon A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand. Copy editors: Gus Mitchell/Maria McGivern. June 2017.

Introduction

Introduction - skin of colour

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

What is melanoma?

Melanoma is a form of skin cancer formed from the uncontrolled growth and replication of melanocytes (pigment cells) [1]. Melanoma is sometimes referred to as malignant melanoma and has a variety of subtypes.

Types of melanoma found in skin of colour

Ungual melanoma

Acral lentiginous melanoma

Nodular melanoma

What is skin of colour?

‘Skin of colour’ is a subjective term used to refer to a natural skin pigmentation ‘darker’ than white (ie, brown or black skin). When compared against a graded assessment of skin colour, such as as the Fitzpatrick phototypes, skin of colour may refer to skin classified as type IV or higher [2]. In some contexts, skin of colour is also used to describe the skin of different non-white ethnic groups, including those of African, Asian, South American, Pacific Island, Maori, Middle Eastern, and Hispanic descent [3]. See ethnic dermatology.

Who gets melanoma?

Melanoma may develop in any skin type, but it is most commonly seen in those with light coloured skin. Conversely, a darker skin colour is associated with a reduced risk of developing melanoma [4]. This trend is evident when comparing the rates of melanoma seen in diverse ethnic groups predisposed to different skin colours.

In the USA during the period from 1999 to 2006, of 288,741 advanced melanoma patients [5]:

- 95% were white

- 0.5% were black

- 0.3% were Asian or Pacific Islanders.

In New Zealand during the period from 1996 to 2006, of 16,425 newly registered cases of melanoma [6]:

- 99% were in New Zealand Europeans

- 1% were in Maori

- 0.2% were in Pacific Islanders

- 0.1% were in Asians.

Skin colour is an independent but significant risk factor for melanoma across diverse ethnic groups, with most cases being diagnosed at a median of 50–65 years of age [5].

People with skin of colour tend to have:

- Thicker melanomas at diagnosis and higher mortality rates [4,7]

- Significantly higher rates of melanomas in areas not exposed to the sun, including the subungual, palmar and plantar surfaces (eg, acral lentiginous melanoma in Pacific Islanders, blacks and Asians) [4,6,7]

- Non-cutaneous melanomas (eg, mucosal melanoma, ocular melanoma) [4–7].

People of all skin colours with a family history of melanoma are at increased risk of developing melanoma due to a genetic predisposition [8].

What causes melanoma?

Melanoma is due to uncontrolled proliferation of melanocytic stem cells following progressive genetic transformations [1,9,10].

In most cases, this genetic change is triggered by sun exposure. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation damages and mutates the DNA [9,10]. In darker skin, a higher content of UV radiation-absorbing melanin is protective [7,11,12], and the use of sunscreens is not required to protect them from melanoma.

Melanoma may also arise in areas not exposed to sunlight and in tissue other than the skin. The rates of these melanomas can be higher in non-white ethnic groups [13].

What are the clinical features of melanoma?

Melanoma can occur anywhere on the skin. In skin of colour, melanoma frequently develops in sites that have low sun exposure, such as the palms or soles (acral lentiginous melanoma) [5,6,14,15]. Less commonly, melanoma may occur on mucous membranes, such as the mouth or genitals, or in other parts of the body, including the brain and the eyes.

- A melanoma may at first appear similar to a freckle or mole and may itch or bleed.

- Colours for melanoma include tan, dark brown, black, blue, red and, occasionally, light grey or a mixture of those colours.

- Melanomas may grow across the skin (ie, in radius — known as the radial growth phase) or grow in depth (known as the vertical growth phase).

It can be harder to identify melanomas, their growth phase, and their pattern in skin of colour as the surrounding skin may mask or match the colour of the melanoma. Characteristic features follow. Note: these features are not always present and do not always indicate malignant growth [1,4].

The Glasgow 7-point checklist

Major features

- Change in size

- Irregular shape

- Irregular colour

Minor features

- Diameter > 7 mm

- Inflammation

- Oozing

- Change in sensation.

The ABCDEs of melanoma

- A: Asymmetry

- B: Border irregularity

- C: Colour variation

- D: Diameter > 6 mm

- E: Evolving (enlarging, changing).

Precursor lesions

Melanoma in skin of colour may develop from normal skin or other skin lesions, including [1,16]:

- Congenital melanocytic naevi (brown or grey birthmarks) — especially large/giant melanocytic naevi

- Benign melanocytic naevi (normal moles).

How is melanoma diagnosed?

Skin lesions of concern are compared with the person’s other skin lesions. If they appear distinctive, they are often examined using by dermoscopy to look for features not otherwise identifiable with the naked eye. Diagnosing melanoma by visual inspection can be difficult — especially in skin of colour where, as mentioned above, the surrounding skin may mask or match the colour of the melanoma [1,4].

Suspicious lesions are then surgically removed for pathological examination (diagnostic excision) using a 2–3 mm margin around the lesion. Partial biopsies are sometimes considered for larger suspicious lesions [1].

Pathological diagnosis of melanocytic lesions can also be difficult. The use of immunohistochemical stains may be considered to confirm whether a suspicious lesion is a melanoma [1].

What is the differential diagnosis for melanoma?

Differential diagnoses for melanoma include:

- Benign melanocytic naevi (moles)

- Basal cell carcinoma (the most common skin cancer in whites, Asians, and Hispanics) [4]

- Squamous cell carcinoma (the most common skin cancer in blacks and Indians) [4]

- Pigmented actinic keratosis

- Seborrhoeic keratosis

- Dermatofibroma

- Pyogenic granuloma

- Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

- Keloid scars

- Cutaneous metastasis.

In skin of colour especially, the following diagnoses should be considered as alternative diagnoses.

Naevi of special sites

Naevi of special sites are naevi that develop in atypical areas, including the genitals, breasts, palms, soles of the feet and flexural regions (armpits, elbows, backs of knees). While benign, they may show a histological structure similar to melanoma. This diagnosis should particularly be considered in skin of colour, as these naevi occur in sites where melanoma commonly occurs in these skin types [5,6,11,14,15].

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is the darkening of the skin following inflammation; this is often is more intense and persistent in skin of colour, which may cause undue distress and confusion in patients [12].

Keloid scarring

A keloid scar is a raised scar that grows beyond the boundaries of the original injury. Keloid scarring is more common in skin of colour and may resemble a resemble a desmoplastic melanoma (which is very rare) [17–19].

What is the treatment for melanoma?

Confirmed melanoma usually undergoes a second surgical procedure known as wide local excision. The clinical margins of this excision are dependent on the size and thickness of the melanoma [1]. The Recommended New Zealand margins for excision of melanoma are as follows:

- Melanoma in situ: 5–10 mm

- Melanoma < 1 mm: 10 mm

- Melanoma 1–2 mm: 10–20 mm

- Melanoma > 2 mm: 20 mm.

It is also important to determine the extent or ‘stage’ of the melanoma and whether it has spread from the site of origin. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cutaneous melanoma staging guidelines (2009) are the commonly used staging criteria. The AJCC staging criteria for cutaneous melanoma are as follows [20]:

- Stage 0: in situ melanoma

- Stage I: thin melanoma < 2 mm in thickness

- Stage II: thick melanoma > 2 mm in thickness

- Stage III: melanoma spread to involve local lymph nodes

- Stage IV: distant metastases have been detected.

Note: non-cutaneous forms of melanoma may have different staging criteria [1,20].

Should lymph nodes be removed?

If a melanoma spreads beyond its site of origin (becoming ‘metastatic melanoma’), the surrounding lymph nodes may become enlarged. In such cases, the lymph nodes should be surgically removed under a general anaesthetic [1].

Normal, unenlarged lymph nodes may also be tested to identify microscopic spread of melanoma; this test is called a sentinel node biopsy and may help in cancer staging [1].

Systemic therapy

Systemic therapies may be offered in cases of advanced melanoma or metastatic melanoma (AJCC stages IIB, IIC and IIIC) [21].

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy involves the use of drugs that stimulate the body’s immune system to work against melanoma cells; it can include:

- Inactive melanoma cells, which may be used to form experimental vaccines

- Interferon α-2b therapy as an adjuvant therapy [21,22]

- The cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) antagonist ipilimumab

- Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) blocking antibodies [23–26] nivolumab and pembrolizumab.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy drugs for melanomas have demonstrated limited success in treating melanoma and are not thought to improve overall survival [21]. They include:

- Dacarbazine

- Fotemustine

- Temozolomide.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy drugs are offered to patients with advanced or non-operable melanomas that express specific mutations [21].

Targeted chemotherapies for melanoma available in New Zealand include [27–32]:

- BRAF inhibitors: dabrafenib and vemurafenib

- MEK inhibitors: trametinib

- Combination BRAF/MEK inhibitor: cobimetinib

- C-KIT inhibitors: imatinib, nilotinib

- PD-1 blocking antibodies: nivolumab, pembrolizumab.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy may be given over several weeks in the treatment of persistent melanomas or melanoma unsuitable for excision. In metastatic melanoma, radiotherapy may be used to alleviate the symptoms associated with metastases [21,33].

What is the outcome for melanoma?

The prognosis for melanoma in skin of colour may be poorer overall compared to melanoma in white skin. This could be due to late presentation or detection leading to thicker melanomas or more aggressive subtypes of melanoma [4–8]. Regardless of skin colour, prognosis is generally dependent on the AJCC stage of melanoma, Clark level of invasion, and Breslow thickness at the time of excision of the primary lesion [1].

The 5-year survival rates (%) according to the simplified AJCC staging classification [34] are as follows:

- Stage I: 90–95%

- Stage II: 45–78%

- Stage III: 26–66%

- Stage IV: 7.5–11%.

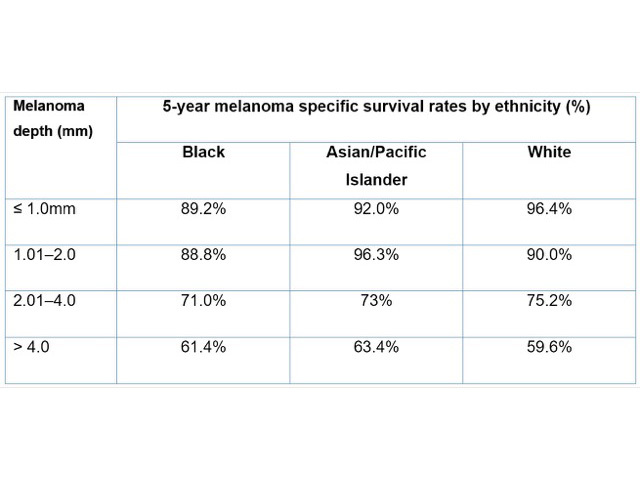

The 5-year survival rates at different tumour depths for differing ethnic groups from 17 US population-based cancer registries in the period from 1999 to 2005 are shown in Table 1 [5].

Table 1. Five-year survival rates by melanoma depth and ethnicity

References

- Oakley A. Melanoma. DermNet New Zealand. 2015. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Roberts WE. Skin type classification systems old and new. Dermatol Clin 2009; 27: 529–33. DOI: 10.1016/j.det.2009.08.006. PubMed

- Taylor SC. Skin of color: biology, structure, function, and implications for dermatologic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46 (2 Suppl): S41–62. PubMed

- Gloster HM Jr, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55: 741–60. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.063. PubMed

- Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999–2006. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65 (5 Suppl 1): S26.e1–S26.e13. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.034. PubMed

- Sneyd MJ, Cox B. Melanoma in Maori, Asian, and Pacific peoples in New Zealand. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009; 18: 1706–13. DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0682. Journal

- Bellew S, Del Rosso JQ, Kim GK. Skin cancer in Asians: part 2: melanoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2009; 2(10): 34. PubMed Central

- Nikolaou V, Stratigos AJ. Emerging trends in the epidemiology of melanoma. Br J Dermatol 2014; 170: 11–19. DOI: 10.1111/bjd.12492. PubMed

- Regad T. Molecular and cellular pathogenesis of melanoma initiation and progression. Cell Mol Life Sci 2013; 70: 4055–65. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-013-1324-2. Nottingham Trent University

- Shain AH, Yeh I, Kovalyshyn I, et al. The genetic evolution of melanoma from precursor lesions. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1926–36. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502583. Journal

- Elder DE. Precursors to melanoma and their mimics: nevi of special sites. Mod Pathol 2006; 19 Suppl 2: S4–20. DOI: 10.1038/modpathol.3800515. Journal

- Kundu RV, Patterson S. Dermatologic conditions in skin of color: Part I. Special considerations for common skin disorders. Am Fam Physician 2013; 87: 850–6. Journal

- Rastrelli M, Tropea S, Rossi CR, Alaibac M. Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo 2014; 28: 1005–11. Journal

- Piliang MP. Acral lentiginous melanoma. Clin Lab Med 2011; 31: 281–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.cll.2011.03.005. PubMed

- Lee HY, Chay WY, Tang MB, Chio MT, Tan SH. Melanoma: differences between Asian and Caucasian patients. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2012; 41: 17–20. Journal

- Crowson AN, Magro CM, Sanchez-Carpintero I, Mihm MC Jr. The precursors of malignant melanoma. In: Dummer R, Nestle FO, Burg G (eds). Cancers of the skin. Recent results in cancer research, vol 160. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2002: 75–84. Chapter abstract

- Kundu RV, Patterson S. Dermatologic conditions in skin of color: Part II. Disorders occurring predominately in skin of color. Am Fam Physician 2013; 87: 859–65. Journal

- Busam KJ. Dermatopathology. A volume in the series: Foundations in diagnostic pathology. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2014.

- Oakley A. Desmoplastic melanoma. DermNet New Zealand. 2011. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 6199–206. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. PubMed Central

- Australian Cancer Network Melanoma Guidelines Revision Working Party, New Zealand Guidelines Group. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of melanoma in Australia and New Zealand. Wellington: the Cancer Council Australia, Australian Cancer Network, and Ministry of Health, New Zealand, 2008. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Ranaweera A. Immunotherapy for melanoma. DermNet New Zealand. 2011. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Ranaweera A. Nivolumab. DermNet New Zealand. 2015. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Ranaweera A. Pembrolizumab. DermNet New Zealand. 2016. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- PHARMAC. Online Pharmaceutical Schedule: Nivolumab. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- PHARMAC. Online Pharmaceutical Schedule: Pembrolizumab. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Ranaweera A. Dabrafenib. DermNet New Zealand. 2013. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Ranaweera A. Vemurafenib. DermNet New Zealand. 2014. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Ranaweera A. Trametinib. DermNet New Zealand. 2013. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Ranaweera A. Imatinib. DermNet New Zealand. 2015. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Ranaweera A. Ipilimumab. DermNet New Zealand. 2015. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Melanoma New Zealand. Getting a diagnosis. (accessed 19 April 2021).

- Mahadevan A. Radiation therapy in the management of melanoma. UpToDate. (accessed 10 January 2017).

- Oakley A. Common benign skin lesions. DermNet New Zealand. 2008. (accessed 10 January 2017).

On DermNet

- About melanoma: for patients

- Melanoma

- Melanoma in situ

- Skin conditions in skin of colour

- Ethnic dermatology

- Skin cancer

- Sun protection

- Skin self examination

- Skin lesions, tumours, and cancers

- Common skin lesions: Melanoma [Continuing Medical Education]

Other websites

- Melanoma Staging: American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th Edition and Beyond — American Joint Committee on Cancer

- Clinical practice guidelines for the management of melanoma in Australia and New Zealand — Cancer Council Australia, Australian Cancer Network, and Ministry of Health, New Zealand

- Online Pharmaceutical Schedule — PHARMAC