Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Last Reviewed: May, 2025

Author: Dr Harriet Bell, Dermatology Registrar, Middlemore Hospital, NZ (2025)

Previous authors: Vanessa Ngan, Staff Writer (2003, 2021)

Peer reviewed by: Dr James A. Ida, MD, MS, Dermatologist, USA (2025)

Reviewing dermatologist: Dr Ian Coulson

Edited by the DermNet content department

Introduction

Demographics

Causes

Clinical features

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Outcome

Eosinophilic fasciitis is a rare fibrosing disorder characterised by oedema and subsequent induration of the skin and subcutaneous tissues. It is typically associated with peripheral eosinophilia.

Eosinophilic fasciitis, also known as diffuse fasciitis or Shulman syndrome, may exhibit overlapping clinical and/or histopathologic features with morphoea. This leads to uncertainty as to whether the two are distinct entities or fall along the same disease spectrum.

Indurated skin thickening causing limited joint mobility due to eosinophilic fasciitis

The epidemiology of eosinophilic fasciitis has yet to be well described. Several case series have reported a mean age at diagnosis to be in the sixth decade. However, reported cases have ranged in age from childhood to the elderly. Eosinophilic fasciitis affects both males and females.

The aetiology and pathogenesis of eosinophilic fasciitis are unknown, although an immune-mediated mechanism is suspected.

While the majority of cases are idiopathic, reported triggers or associated factors include:

Eosinophilic fasciitis is typically acute in onset, with cutaneous findings evolving over time. The extremities, trunk, and neck are most commonly involved and most patients have bilateral skin changes, which may include:

Extension of skin changes to the distal digits is characteristically absent, which can be a helpful finding to distinguish eosinophilic fasciitis from systemic sclerosis.

Extra-cutaneous features include:

Induration of the skin and the” groove sign” - an indentation along the course of a superficial vein

“Orange skin” thickening and a “groove sign”

Eosinophilic fasciitis should be suspected based on typical clinical findings and confirmed on deep skin-to-muscle incisional biopsy.

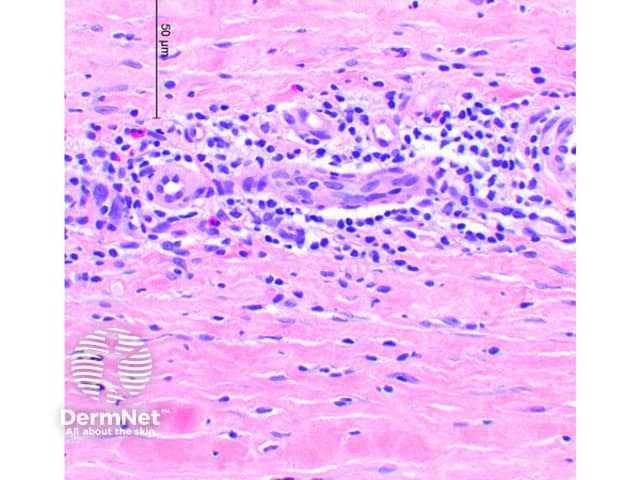

Histological features of eosinophilic fasciitis include:

An inflammatory infiltrate with scattered eosinophils in the perimuscular fascia

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be useful to highlight areas of fascial inflammation, as demonstrated by increased T2 signal in the subcutaneous and deep fascia.

The following blood test abnormalities may be observed:

Physical and occupational therapy are important for maintaining joint mobility and preventing contractures.

Treatment should be initiated as soon as possible after the diagnosis is made.

First-line: Systemic steroids (eg, oral prednisone or pulse intravenous methylprednisolone). A starting dose equivalent to 1 mg/kg of prednisone per day is suggested, which is tapered over 6–24 months as tolerated.

Second-line agents (eg, DMARDs) may be added to improve therapeutic response and/or to spare the use of steroids and these include:

Once remission is achieved, therapy is maintained for several months before an attempt at discontinuation.

For refractory disease, various other treatments have been reported, including:

Eosinophilic fasciitis typically responds to treatment within the first few weeks, with clinical improvement seen over many months. The reported rate of complete response is 60–69%.

Diagnostic delay has been associated with a lower likelihood of response to treatment. Patients with incomplete response may develop chronic thickening of the skin and contractures.

Some patients with eosinophilic fasciitis may improve spontaneously without treatment.