Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Hydroxychloroquine — extra information

Hydroxychloroquine

Authors: Dr Anes Yang, Clinical Researcher, Department of Dermatology, St George Hospital; Dr Monisha Gupta, Senior Staff Specialist, Department of Dermatology, Liverpool Hospital, NSW, Australia. September 2018.

Introduction

Demographics

Contraindications

More information

How it works

Dosing

Side effects

Drug interactions

Pregnancy

Monitoring

What is hydroxychloroquine?

Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil®) is a 4-amino-quinoline antimalarial medication that is widely used to treat systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, and related inflammatory and dermatological conditions. It is a hydroxylated version of chloroquine, with a similar mechanism of action. However, following an identical dose of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, tissue levels of chloroquine are 2.5 times those of hydroxychloroquine. Hydroxychloroquine is preferred due to its safer profile.

If there is a contraindication to hydroxychloroquine, an alternative antimalarial medication used in dermatology is quinacrine. Due to differences in chemical structure, there is no cross-reactivity between the 4-aminoquinolines (chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine) and quinacrine. An adverse reaction to one does not preclude the use of the other.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Porphyria cutanea tarda

Urticarial vasculitis

Who uses hydroxychloroquine?

Hydroxychloroquine is used as a first-line medication for the following indications in dermatology:

Hydroxychloroquine is used as a second- or third-line treatment option for the following in dermatology:

Other dermatological conditions where hydroxychloroquine may be considered include:

- Actinic prurigo

- Actinic reticuloid

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

- Atopic dermatitis

- Chronic actinic dermatitis

- Chronic erythema nodosum

- Cutaneous CD8+ pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma

- Elastolytic giant cell granuloma

- Eosinophilic fasciitis

- Epidermolysis bullosa

- Follicular mucinosis

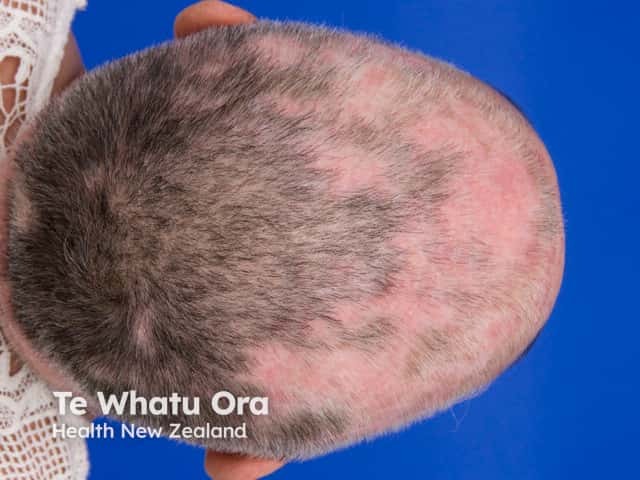

- Frontal fibrosing alopecia

- Graft versus host disease

- Histiocytic necrotising lymphadenitis (Kikuchi Fujimoto disease)

- Lichen planus and its variants (eg, actinic, erosive, and lichen planopilaris)

- Lichen sclerosus

- Lipodermatosclerosis

- Morphoea

- Necrobiosis lipoidica

- Reticular erythematous mucinosis

- Schnitzler syndrome

- Solar urticaria

- Systemic sclerosis

- Urticaria

- Urticarial vasculitis

- Idiopathic nodular panniculitis.

What are the contraindications with hydroxychloroquine?

The contraindications to hydroxychloroquine include:

- Known hypersensitivity to hydroxychloroquine or 4-aminoquinoline

- Children under six years of age, due to the increased risk of overdose

- Patients taking tamoxifen as tamoxifen increases the risk of retinopathy

- Patients with severe renal impairment, who require dose reduction

- Patients with pre-existing retinopathy of the eye — this is a relative contraindication in that it makes patient monitoring more difficult.

Tell me more about hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine has a lower risk of ocular toxicity, both corneal and retinal, compared with chloroquine.

Smoking possibly reduces the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine, although studies have not usually confirmed this clinical impression.

Hydroxychloroquine is considered safer than chloroquine during pregnancy and lactation.

Hydroxychloroquine is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, and steady-state concentrations are reached after 4–6 weeks; 45% of hydroxychloroquine binds to plasma proteins that are deposited in tissues such as the liver, spleen, kidney, and lung. There is an unusually high affinity for melanin-containing cells (eg, in the skin and retina). Deposits in these cells can lead to cutaneous pigmentation and possibly retinal toxicity.

Hydroxychloroquine breaks down into two pharmacologically active metabolites — desethyl-hydroxychloroquine and desethyl-chloroquine.

After a single dose, hydroxychloroquine is excreted mainly in the faeces, and only 20% is excreted unchanged in the urine. Dose adjustment is therefore only required in patients with severe renal impairment.

How does hydroxychloroquine work?

Hydroxychloroquine is:

- Anti-inflammatory

- Antiproliferative

- Immunomodulatory

- Antithrombotic

- Photoprotective.

Anti-inflammatory effects are thought to result through a variety of pathways reducing the cascade of cytokine production and including actions related to an increase in lysosome pH. This causes:

- Decreased protease activity

- Decreased class II major histocompatibility complex assembly

- Reduced activation of Toll-like receptors 9, 7, 8, and 3

- Increased CD8 T-cell stimulation.

These lysosomotropic effects occur in macrophages, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes. Hydroxychloroquine has a two-fold impact on T cells. It inhibits CD4 T-cell stimulation, but also promotes CD8 T-cell stimulation. The combined effect is a beneficial action in autoimmunity without a penalty of increased opportunistic infections.

Antiproliferative and immunomodulatory effects are mediated by decreasing lymphocyte proliferation, interference with natural killer cell activity, and possibly the alteration of auto-antibody production.

The photoprotective effects of hydroxychloroquine are not entirely understood. Current theories include that the:

- Accumulation of hydroxychloroquine in the skin provides a physical photoprotective barrier by absorbing specific wavelengths of light

- The antimalarial medication's anti-inflammatory effect dampens the inflammatory response of keratinocytes usually triggered by sunlight exposure.

Antimalarial medications prevent platelet aggregation and act as prostaglandin antagonists due to the inhibition of phospholipase A2. Therefore, hydroxychloroquine may be used as a life-long therapy for patients with systemic lupus who are at an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Other effects of hydroxychloroquine include:

- A 15–20% decrease in serum cholesterol, triglyceride, and low-density lipoprotein levels

- Lowering glucose by decreasing insulin degradation

- Antiviral properties

- Antineoplastic action

- Increasing the patient's bone mineral density measured in the spine and the hips.

Dosing of hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine is dispensed as 200 mg tablets, which is equivalent to 155 mg of the base.

Hydroxychloroquine should be taken with a meal or a glass of milk to minimise the gastrointestinal side effects.

Alternate-day dosing can be used. For example, hydroxychloroquine 400 mg alternating with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily can be used to reach effective daily dosing of 300 mg/day.

If a therapeutic response is not achieved with hydroxychloroquine alone, adding quinacrine may improve the therapeutic effect.

Dosing recommendations in lupus erythematosus

For the treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, the usual dose range is 200–400 mg daily until a therapeutic response is achieved. Although maximum doses were previously calculated on the patient's ideal body weight and advised not to exceed 6.5 mg/kg/days, dosing is now recommended not to exceed 5.0 mg/kg/days actual body weight. However, this recommendation may require adjustment in obese patients as the maximum daily dose should not exceed 400 mg/days.

To minimise the cumulative dose, which is also believed to be of some importance in the development of retinal toxicity, the dose should be reduced as tolerated (over the winter months).

Dosing recommendations in porphyria cutanea tarda

In the treatment of porphyria cutanea tarda, hydroxychloroquine 100 mg should be prescribed twice weekly for one month, then 200 mg/day until plasma porphyrin levels are normal for at least a month. Initial higher doses may lead to hepatotoxicity as a result of rapid mobilisation of hepatic porphyrin stores.

There are no dosage adjustments provided in the manufacturer’s labelling for renal or hepatic impairment; however, dose reduction may be needed in patients with severe renal impairment.

What are the side effects and risks of hydroxychloroquine?

Ocular side effects

Hydroxychloroquine can cause irreversible retinal toxicity, resulting in bilateral bull’s eye retinopathy, but is regarded as less toxic to the retina than chloroquine and it does not cause the corneal deposits seen with chloroquine therapy.

Irreversible retinal toxicity from hydroxychloroquine has been recognised for many years, with the bull’s eye retinopathy seen as the end-stage of this process. The high affinity for melanin-containing cells such as those found in the retinal pigment epithelium is hypothesised to be the cause.

Recent research has suggested that damage patterns vary with ethnicity, and those of Asian heritage present with a more peripherally distributed area of damage compared to the classic bull’s eye pattern seen in Caucasian patients.

The risk of retinal toxicity is dependent on several factors:

- A daily dose of hydroxychloroquine >5.0 mg/kg using the patient's body weight

- Severe renal impairment

- Concomitant use of tamoxifen

- Duration of use >5 years.

In 2016, with new scientific data, the American Academy of Ophthalmology revised the screening recommendations for patients being commenced on long-term hydroxychloroquine therapy. A fundus examination alone is insufficient for screening, and further tests are required including at least automated visual field testing and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography.

Every patient should undergo a baseline ophthalmic examination within the first year of commencing hydroxychloroquine if long-term use is anticipated. In the absence of risk factors listed above, annual screening should then be performed after five years.

Sunglasses can be recommended to avoid additional retinal injury due to sun exposure.

Patients with hydroxychloroquine-induced retinal toxicity will not have any visual symptoms in the early stages, and will only develop clinical symptoms with severe end-stage damage. Therefore, it is essential that the screening recommendations outlined above are followed, and hydroxychloroquine should be ceased if there are signs of definite retinopathy. The retinopathy does not reverse, but the progression is rare after hydroxychloroquine is discontinued.

Visual symptoms may present as paracentral scotomas (islands of vision loss) when reading. If blurring or vision changes occur, hydroxychloroquine should be ceased, and a careful eye examination conducted.

Gastrointestinal effects

Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea are common side effects, but are usually transient or resolve on the reduction of the dose. They can be minimised by taking the hydroxychloroquine with food.

Cutaneous effects

Blue–grey pigmentation of the skin affects up to 25% of patients taking hydroxychloroquine, especially where there has been bruising. Transverse pigmented nail bands and mucosal pigmentation have also been reported.

Rashes may occur in up to 10% of patients, most commonly morbilliform or psoriasiform. Note that adverse cutaneous reactions to hydroxychloroquine are reported to affect more than 30% of patients with dermatomyositis, compared to a lower risk of rash in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. If a rash appears, hydroxychloroquine should be withdrawn and may be restarted at a lower dose.

Less common skin side effects may include:

- Urticaria

- Lichenoid eruptions

- Alopecia

- Photosensitivity

- Exfoliative dermatitis

- Erythema annulare centrifugum

- Severe cutaneous adverse reactions

- Bleaching of hair.

Haematological effects

Haematological side effects are rare. Haemolysis in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, aplastic anaemia, and leukopenia has been reported. The most extensive study to date evaluating G6PD deficiency with concurrent use of hydroxychloroquine reported no episodes of haemolysis in over 700 months of exposure among the 11 studied patients with G6PD deficiency. Routine screening for G6PD deficiency is no longer recommended for hydroxychloroquine.

Drug interactions with hydroxychloroquine

Drug interactions seen with hydroxychloroquine include:

- Increased plasma levels of:

- Digoxin

- Methotrexate

- D-penicillamine

- Ciclosporin

- Beta blockers.

- Decreased bioavailability of penicillin

- Increased levels of hydroxychloroquine:

- Cimetidine

- Ritonavir

- Reduced levels of hydroxychloroquine:

- Cholestyramine

- Antacids.

- Increased risk of myopathy with:

- Aminoglycosides

- Systemic corticosteroids

- A decreased effect of:

- Neostigmine

- Physostigmine.

Pregnancy and hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine does cross the placenta and is considered Category D in pregnancy (see DermNet's pages on Safety of medicines taken during pregnancy and on Lactation and medications used in dermatology).

However, in multiple studies, hydroxychloroquine use has not been associated with congenital disabilities, stillbirth, prematurity, low birth weight, fetal death, or retinopathy following maternal intake at recommended doses.

Hydroxychloroquine has been reported to reduce the risk of cardiac manifestations of neonatal lupus in pregnant women with antiSSA/Ro autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus.

International experts currently recommend that hydroxychloroquine can continue during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Hydroxychloroquine is regarded as safer than chloroquine if required in women planning a pregnancy or breastfeeding.

What monitoring is required with hydroxychloroquine?

The amount of monitoring with hydroxychloroquine varies from centre to centre. More frequent surveillance is needed if laboratory values are abnormal or with high-risk patients.

- The patient's full blood count, renal function, and liver function should be examined at baseline, then checked periodically.

- A pregnancy test is undertaken at baseline in women of childbearing age, and the use of a reliable method of contraception during treatment is recommended.

- Every patient should undergo a baseline ophthalmic examination within the first year of commencing therapy. In the absence of additional risk factors, annual screening should be performed after five years.

Hydroxychloroquine levels can be measured in the blood. This can potentially be used for monitoring the patient's adherence to treatment and where the response has been inadequate. No standardised effective reference level has been validated. Cohorts with significant improvement or remission of their systemic lupus have had hydroxychloroquine blood levels of >750 ng/mL; a blood level of >500 ng/mL is considered as adherent.

Approved datasheets are the official source of information for medicines, including approved uses, doses, and safety information. Check the individual datasheet in your country for information about medicines.

We suggest you refer to your national drug approval agency such as the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), UK Medicines and Healthcare products regulatory agency (MHRA) / emc, and NZ Medsafe, or a national or state-approved formulary eg, the New Zealand Formulary (NZF) and New Zealand Formulary for Children (NZFC) and the British National Formulary (BNF) and British National Formulary for Children (BNFC).

References

- Browning DJ. Pharmacology of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. In: Browning DJ (ed). Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine retinopathy. New York: Springer, 2014: 35–63.

- Rodriguez-Caruncho C, Bielsa Marsol I. Antimalarials in dermatology: mechanism of action, indications, and side effects. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2014; 105: 243–52. DOI: 10.1016/j.adengl.2012.10.021. PubMed

- Kalia S, Dutz JP. New concepts in antimalarial use and mode of action in dermatology. Dermatol Ther 2007; 20: 160–74. DOI: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00131.x. PubMed

- Platais C, Lalagianni N, Momen S, Ormond M, McParland H, Setterfield J. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in oral lichen planus: a retrospective review. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188(4):557-558. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljac113 Journal

- Schoenfeld SR, Kasturi S, Costenbader KH. The epidemiology of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease among patients with SLE: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013; 43: 77–95. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.12.002. PubMed

- Singal AK, Kormos-Hallberg C, Lee C, et al. Low-dose hydroxychloroquine is as effective as phlebotomy in treatment of patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 1402–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.038. PubMed

- Wolverton SE. Comprehensive dermatologic drug therapy, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012.

- Marmor MF, Kellner U, Lai TY, Melles RB, Mieler WF; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy (2016 revision). Ophthalmology 2016; 123: 1386–94. DOI: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.058. PubMed

- Mohammad S, Clowse MEB, Eudy AM, Criscione-Schreiber LG. Examination of hydroxychloroquine use and hemolytic anemia in G6PDH-deficient patients. Arthritis Care Res 2018; 70: 481–5. DOI: 10.1002/acr.23296. PubMed

- Motta M, Tincani A, Faden D, et al. Follow-up of infants exposed to hydroxychloroquine given to mothers during pregnancy and lactation. J Perinatol 2005; 25: 86–9. DOI: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211208. PubMed

- Klinger G, Morad Y, Westall CA, et al. Ocular toxicity and antenatal exposure to chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for rheumatic diseases. Lancet 2001; 358: 813–14. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06004-4. PubMed

- Parke A, West B. Hydroxychloroquine in pregnant patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 1996; 23: 1715–18. PubMed

- Izmirly PM, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Pisoni CN, Khamashta MA, Kim MY, Saxena A, Friedman D, Llanos C, Piette JC, Buyon JP. Maternal use of hydroxychloroquine is associated with a reduced risk of recurrent anti-SSA/Ro-antibody-associated cardiac manifestations of neonatal lupus. Circulation, 2012; 126: 76–82. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.089268. PubMed

- Flint J, Panchal S, Hurrell A, et al; BSR and BHPR Standards, Guidelines and Audit Working Group. BSR and BHPR guideline on prescribing drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding-Part I: standard and biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and corticosteroids. Rheumatology 2016; 55: 1693–7. DOI: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev404. PubMed

- Kavanaugh A, Cush JJ, Ahmed MS, et al. Proceedings from the American College of Rheumatology Reproductive Health Summit: the management of fertility, pregnancy, and lactation in women with autoimmune and systemic inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Care Res 2015; 67: 313–25. DOI: 10.1002/acr.22516. PubMed

- Fernandez AP. Updated recommendations on the use of hydroxychloroquine in dermatologic practice. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76: 1176–82. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.012. PubMed

- Pelle MT, Callen JP. Adverse cutaneous reactions to hydroxychloroquine are more common in patients with dermatomyositis than in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 2002 Sep;138(9):1231–3; discussion 1233. PubMed

On DermNet

- Antimalarial medications in dermatology

- Chloroquine

- Quinacrine

- Oral medications for skin diseases

- Cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- Porphyria cutanea tarda

Other websites

- Recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy — 2016 — American Academy of Ophthalmology

- Data sheets and consumer medicine information — Medsafe New Zealand

- Hydroxychloroquine patient information — Medsafe New Zealand (PDF file)

- Hydroxychloroquine (for rheumatoid arthritis) patient information — My Medicines New Zealand