Main menu

Common skin conditions

NEWS

Join DermNet PRO

Read more

Quick links

Vitiligo — extra information

Autoimmune/autoinflammatory Pigmentary disorders

Vitiligo

Author: Dr Bushra Alsayaydeh, Dermatologist, Amman, Jordan, August 2022. Previously: A/Prof Amanda Oakley, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand, 1999.

Introduction

Demographic

Causes

Clinical features

Classification

Severity assessment

Variation in skin types

Complications

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses

Treatment

Prevention

Outcome

What is vitiligo?

Vitiligo is an acquired, chronic, depigmenting disorder of the skin, in which pigment-producing cells (melanocytes) that determine the colour of skin, hair, and eyes are progressively lost. It appears as milky-white patches of skin (leukoderma) and can be cosmetically very disabling, particularly in people with dark skin.

It is currently widely accepted that vitiligo is the result of autoimmune destruction of melanocytes.

Vitiligo over the knuckles - keobnerisation due to trauma often localises vitiligo

Symmetrical wrist vitiligo - a common location (V-patient1)

Vitiligo over the back and elbows

Vitiligo on the lid with poliosis of the lashes

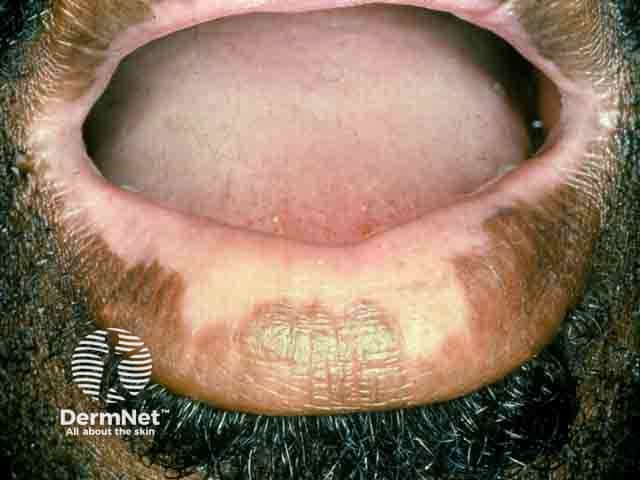

Vitiligo on the lips

Follicular repigmentation in a patch of vitiligo

Extensive symmetrical facial vitiligo

Vitiligo around the hairline of a Samoan woman (V-patient3)

Click here for more images of vitiligo

Who gets vitiligo?

Vitiligo affects 0.5–2% of the population.

- Race: relatively consistent incidence in all races, but appears to be:

- Less common in the Han Chinese population

- More common in India (up to 8.8% of the population).

- Sex: both men and women appear to be equally affected

- Women tend to constitute a higher percentage of overall outpatient visits, due to greater concerns about cosmetic appearance.

- Onset: the average age of onset is between 20–24 years, but can occur at any age. Typically, there are two peaks of onset, early (<10 years) or late (around 30 years).

- 41% of segmental vitiligo cases start before the age of 10.

- 50% of non-segmental vitiligo cases start before the age of 20.

- 80% of all cases present before the age of 30.

- Inheritance: follows a polygenic pattern, with a 23% monozygotic twin concordance, supporting the cause of vitiligo to be multifactorial (genetic and non-genetic environmental factors).

- More than 20–30% of the affected individuals report vitiligo in a first or second-degree relative.

Autoimmune disease development has been associated with generalized vitiligo, the most common type of vitiligo, especially if there is a family history of vitiligo and other autoimmune disorders.

- The strongest association is with thyroid disease, which can affect up to 15% of adults and 5–10% of children with vitiligo.

- Other less frequently associated autoimmune disorders with vitiligo are:

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (mostly adult-onset)

- Pernicious anaemia (B12 deficiency)

- Addison disease

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Alopecia areata

- Other autoimmune dermatologic conditions, eg, psoriasis and lichen sclerosus.

Vitiligo is also three times more common in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow and stem-cell transplants than in the healthy population.

What causes vitiligo?

Vitiligo is due to the loss or destruction of melanocytes (melanin-producing cells).

Genetic factors appear to contribute to 80% of vitiligo risk, whilst environmental factors account for 20%. Many genetic loci have been identified, all related to the immune system, except for TYR which encodes tyrosinase, a key enzyme in melanin production and a major autoantigen in vitiligo.

The convergence or integrated theory combines immunological, biochemical, oxidative, and environmental mechanisms that work jointly in those with a genetic susceptibility is widely accepted.

This could be explained through three phases:

- Initial phase: less adhesive melanocytes are prone to internal and external oxidative stresses, leading to the production of more toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS).

- Progression phase: an imbalance between ROS and antioxidants will activate the adaptive immune system bridged by the innate immune system.

- CD8+ cytotoxic cells release cytokines, mainly interferon-γ (INF-γ) that activate the JAK-STAT pathway through its receptors on keratinocytes. This will lead to the production of chemokines (CXC), predominantly by keratinocytes, but also by melanocytes themselves, leading to IFN-γ–CXCR3- CXCL9/10 axis loop feedback.

- Acting together on their common CXCR3 receptor, CXCL9 drives the main bulk of CD8+ cell homing, while CXCL10 promotes their localisation to affected skin lesions and induction of melanocyte apoptosis through CXC3B activation. Of note, where both humoral (antibody) and T-cell responses appear to be implicated, antibody titres do not correlate with disease activity nor the localisation of distinct vitiligo lesions.

- Maintenance phase: established lesions are maintained by resident melanocyte reactive T-cells (TRM cells), through the IL15-dependent pathway. These TRM cells may be responsible for what is called an ‘autoimmune memory’, in which relapses occur mostly at the same exact site of previous lesions.

Understanding the molecular pathogenesis of vitiligo serves as a promising source for the development of more targeted therapies.

Vitiligo and other conditions

Vitiligo is also a component of some rare multiorgan syndromes, such as:

These syndromes affect organs that normally house melanocytes, and are now believed to constitute one disease entity with variable clinical expression.

Other rare dermatologic syndromes that present with lesions indistinguishable from vitiligo are:

A vitiligo-like leukoderma may occur in patients with metastatic melanoma.

Vitiligo can also be induced by drugs, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (pembrolizumab, nivolumab) and BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib) used to treat metastatic melanoma.

What are the clinical features of vitiligo?

The onset of vitiligo is usually insidious.

The most common presentation is the complete loss of pigment in single or multiple macules or patches of skin, with characteristic chalk- or milky-white colour.

Lesion characteristics

- Typically asymptomatic, but rarely pruritic in active lesions.

- Multiple macules are sometimes described as confetti-like.

- Well-defined with convex borders; the borders may sometimes either be:

- The colour of unaffected skin

- Hyperpigmented or hypopigmented

- Inflamed and red.

- Sometimes smaller patches coalesce, merging into more complex shapes.

Location

- Can be found on any part of the body, although more common in sun-exposed areas or areas more prone to repetitive trauma (eg, eyelids, lips, nostrils, fingertips, and toes), body folds (armpits, groin, navel), and nipples. Interestingly, these areas are naturally more pigmented.

- Vitiligo also favours sites of injury; this is called the isomorphic Koebner phenomenon. Injury can be induced by either:

- Physical (cuts, abrasions, scratching)

- Mechanical (friction, chronic pressure, eg, eye rubbing, lip-licking, watches, tight-fitting clothes)

- Burns (chemical, sunburn)

- Inflammation (psoriasis, herpes zoster, dermatitis)

- Therapeutic (phototherapy, radiotherapy).

- Vitiligo can occur in less pigmented areas of skin that can be often overlooked especially in light-skinned patients, eg, the palms and soles, and oral mucosa.

Precipitating factors and other features

- Emotional stress, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, vitamin deficiencies, and many other factors have been described as precipitating factors for vitiligo; however, correlation is still not proven.

- Vitiligo may occasionally start as multiple halo naevi.

- Found in up to 31% of cases.

- Halo naevi can precede or coincide with vitiligo.

- Loss of hair colour, (leukotrichia or poliosis), may affect the scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair in 10–60% of patients. It does not correlate with disease activity, but could be a predictor of poorer response to therapy due to the destruction of melanocyte reservoir in hair follicles.

- Premature hair greying has been described but the association is still uncertain.

- The retina may be affected, however, the colour of the iris does not change.

- Sensory hearing impairment has been described in some patients with vitiligo, presumably due to cochlear melanocyte loss, but clear evidence is lacking.

- Sunburn in vitiligo lesions may be a problem

- Some evidence suggests that people with vitiligo might have a lower risk for internal malignancies and skin cancer.

- Two nationwide retrospective studies from South Korea and Taiwan, have shown that vitiligo patients are at lower risk of internal malignancies, in addition to lower BCC and SCC risk in the Taiwanese study.

- Another retrospective study of 1307 vitiligo patients found individuals with vitiligo are at lower risk for both melanoma and NMSC. However, some of these studies found a possible higher risk for thyroid cancer.

Severity

Severity is variable and there is no way to predict how much or how fast pigment will be lost.

- Vitiligo appears more evident in patients with naturally dark skin.

- Extension of vitiligo can occur over a few months, then it stabilises.

- Some spontaneous repigmentation may occur from the hair follicles, and the overall size of the white patch may reduce.

- At some time in the future, the vitiligo is likely to extend again.

- Cycles of pigment loss followed by periods of stability may continue indefinitely.

- Light-skinned people usually notice pigment loss during the summer as the contrast between the affected skin and suntanned skin becomes more distinct.

- The pigment has occasionally been reported to be lost from the entire skin surface.

- Active disease predictors are peripheral hypopigmentation, confetti-like depigmentation, ill- rather than well-defined borders, and the Koebner phenomenon.

For more information, see the section on severity assessment below.

How is vitiligo classified?

The Vitiligo European Task Force (VETF) came to a consensus about the classification of vitiligo in 2007. They decided on four main categories with subtypes.

Classification |

Subtypes |

Comments |

Non-segmental vitiligo |

|

|

Segmental vitiligo |

|

|

Mixed vitiligo |

|

|

Unclassified vitiligo |

|

|

More than 90% of the adult vitiligo cases are of the generalized vulgaris or acrofacial types, while in children, segmental vitiligo constitutes 15–30% of the cases.

Rare clinical subtypes of vitiligo include:

- Trichrome vitiligo: describes three shades of skin colour, where there is an intermediate hypopigmented hue between the white patch and the normal skin.

- Quadrichrome and pentachrome vitiligo: four and five shades of colours has been rarely described with multiple shades of tan brown, in addition to white and normal skin colour.

- Red vitiligo: white patches that have raised, red, inflammatory borders.

- Blue vitiligo: post-inflammatory patches with a bluish-grey hue that correlate histologically with pigment incontinence in dermal melanophages.

Click here for images of vitiligo

How is the severity of vitiligo assessed?

In most cases, the severity of vitiligo is not formally assessed. However, clinical photographs may be taken to monitor the condition.

At least two scoring systems have been devised for vitiligo and are used in clinical trials.

- Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI)

- Vitiligo European Task Force (VETF) system

VASI

VASI is based on the PASI scoring system for psoriasis. It measures the extent and degree of depigmentation in 6 sites: hands, upper extremities, trunk, lower extremities/feet, and the head and neck.

VETF

VETF is based on SCORAD scoring system for atopic dermatitis. The VETF assesses the extent, staging, and spreading/progression in 5 sites: head/neck, trunk, arms, legs and hands/feet. It grades from 0 (normal pigmentation) to 4 (complete hair whitening). Spreading is assessed using the following scores: 0 (stable disease), -1 (regressive disease) and +1 (progressive disease).

VETF includes a clinical assessment form to record the sex, age, duration of disease, age of onset, episodes of repigmentation, the impact of vitiligo on quality of life, family history, additional medical conditions, and the Fitzpatrick skin type of the patients.

How do clinical features vary in differing types of skin?

The distribution and characteristics of vitiligo patches are similar in different skin types; however, while vitiligo can be barely noticeable in some people with lighter skin complexions, it is usually more obvious in darker skin types. This can cause significant cosmetic disability, along with its psychological consequences.

What are the complications of vitiligo?

- Cosmetically disabling

- Psychosocial stresses and social stigmata to affected individuals, particularly in people with dark skin.

- Higher risk of acquiring an associated autoimmune condition among individuals with vitiligo compared to the general population.

Vitiligo has an otherwise benign nature with most of those affected being in good health.

How is vitiligo diagnosed?

Vitiligo is usually a clinical diagnosis, based on its characteristic appearance, and no specific tests are required to make the diagnosis.

Tools that can aid in diagnosis include:

-

- Enhances white patches, making it easier to see less conspicuous lesions.

- Especially helpful in light-skinned people, patches with partial loss of pigment, or to monitor response to therapy.

- The UVA is absorbed by collagen fibres in the dermis, and fluoresces back as bright white in absence of epidermal melanin (which normally absorbs UVA).

-

- Characteristically shows a white glow, with some clues that can help in differentiating between stable and active disease [see Dermoscopy of vitiligo].

-

- Occasionally recommended, particularly in early or inflammatory vitiligo, when a lymphocytic infiltration may be observed.

- Where melanocytes are typically absent in the epidermis of established vitiligo patches, some argue that total loss of melanocytes never occurs, indicating potential functionality restoration with treatment.

-

Blood tests

- To assess other potential autoimmune diseases or polyglandular syndromes may be arranged, especially if combined with a positive family history

- Examples include thyroid function tests, ANA, and B12 levels.

What is the differential diagnosis for vitiligo?

For localised vitiligo lesions

For generalised vitiligo

Inherited hypomelanosis

- Piebaldism.

- Waardenburg syndrome.

- Tuberous sclerosis.

- Hypomelanosis of Ito (pigmentary mosaicism).

Secondary hypomelanosis

- Infectious: pityriasis versicolor, leprosy (tuberculoid/lepromatous), secondary syphilis, treponematosis and onchocerciasis (late stages).

- Post-inflammatory: lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, morphoea/ scleroderma, discoid lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, and after-burn.

- Paraneoplastic: cutaneous lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), cutaneous melanoma (localized/ distant autoimmune reaction)

- Drug/ toxin-induced:

- Systemic: imatinib, chloroquine, fluphenazine, physostigmine, targeted melanoma immunotherapy.

- Topical: imiquimod, corticosteroids.

- Occupational exposure: phenolic compounds; mainly on exposed skin (hands, face).

Idiopathic

What is the treatment for vitiligo?

There is no cure for vitiligo and treatment is often unsatisfactory. The aim is to stop progression of the disease (stabilisation), and to achieve satisfactory re-pigmentation.

Treatment is most successful on the face and trunk; whereas hands, feet, and areas with white hair respond poorly. Compared to long-standing patches, new ones are more likely to respond to medical therapy.

While the hair follicle is the main source of pigment restoration, another potential reservoir can be at the borders of the white patches. When successful re-pigmentation occurs, melanocyte stem cells (DOPA-negative) in the middle and lower outer root sheath (ORS), or bulge at the base of the hair follicle are activated (become larger, with intense DOPA oxidase activity). They migrate to the skin surface to form pigment islands, appearing as perifollicular brown macules. Otherwise, re-pigmentation can occur in less common patterns such as marginal, diffuse, or combined.

Treatment response is evaluated in terms of proportion of skin that has retained pigment. In studies, a good response is usually translated as > 50% or 75%, depending on the study’s design.

General measures

A cut, graze, or scratch may lead to a new patch of vitiligo

- Minimise skin injury by wearing protective loose-fitting clothing.

Cosmetic camouflage can disguise vitiligo. Options include:

- Make-up, dyes, and stains

- Waterproof products

- Dihydroxyacetone-containing products — "tan without the sun."

- Micropigmentation or tattooing for stable vitiligo.

Sun protection with clothing, sunscreen use, and lifestyle modification.

- Depigmented skin can only burn on exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR); it cannot tan.

- Sunburn may cause vitiligo to spread.

- Tanning of normal skin makes vitiligo patches appear more visible.

Specific measures

There are several modalities that are proven to be helpful in vitiligo. Optimal therapeutic response is often seen with combination therapies.

Topical treatments

-

- Can be used on the trunk and limbs for up to 3 months.

-

Calcineurin inhibitors (pimecrolimus cream and tacrolimus ointment)

- Preferred for vitiligo affecting the eyelids, face, neck, armpits, and groin, because, unlike topical steroids, they do not cause skin atrophy.

-

Topical vitamin D derivatives (calcipotriol, tacalcitol)

- Second line; effective only as combination therapy.

-

Ruxolitinib cream

- A Janus kinase 1 and 2 inhibitor that is FDA approved for the treatment of non-segmental vitiligo in adult and paediatric patients 12 years of age and older.

- Significant clinical improvement for facial vitiligo, in individuals 12 years and older with non-segmental vitiligo with 10% or less affected BSA, with sustained safety after 52 weeks has been seen in two phase 3 double-blind clinical trials. Body vitiligo showed less dramatic response.

-

Other controversial therapies include pseudocatalase and topical prostaglandin inhibitors

- Further studies are needed to confirm efficacy.

Phototherapy

Phototherapy refers to treatment with ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Options include:

- Whole-body or localised UVB phototherapy

- Excimer laser UVB (308 nm) or targeted UVB for small areas of vitiligo

- Oral, topical, or bathwater photochemotherapy (PUVA)

- In-office or home phototherapy.

Phototherapy probably works in vitiligo by two mechanisms.

- Immune suppression — preventing the destruction of the melanocytes

- Stimulation of cytokines (growth factors).

Treatment is usually given twice weekly for a trial period of 3–4 months. If re-pigmentation is observed, treatment is continued until re-pigmentation is complete or for a maximum of 1–2 years.

- Phototherapy is unsuitable for very fair-skinned people.

- The treatment intensity aims for the vitiligo skin to be a light "carnation" pink.

- If re-pigmentation is observed, treatment is continued until re-pigmentation is complete or for a maximum of 1–2 years.

- It is essential to avoid burning (red, blistered, peeling, itchy or painful skin), as this could cause the vitiligo to get worse.

A meta-analysis of 35 different studies reporting outcomes after phototherapy for generalised vitiligo. A marked or clinically useful response was achieved in 36% after 12 months of narrowband UVB and in 62% after 12 months of PUVA. The face and neck responded better than the trunk, which responded better than the extremities. It was not very effective on the hands and feet.

Systemic therapy

-

- Short pulse therapy to slow rapid progression, or as mini-pulse oral steroids to stabilize active disease, eg, dexamethasone 2.5–4 mg, for two consecutive days per week, for 3–6 months.

-

Oral minocycline 100 mg/day, a tetracycline antibiotic with anti-inflammatory properties

-

Subcutaneous afamelanotide

- An α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) analogue. Showed superior re-pigmentation when combined with NB-UVB, but excessive tanning in unaffected surrounding skin made final cosmetic results less satisfying.

None of these treatments are based on randomised controlled trial data.

Surgical treatment of stable vitiligo

Surgical treatment for stable and segmental vitiligo requires removal of the top layer of vitiligo skin (by shaving, dermabrasion, sandpapering, or laser) and replacement with pigmented skin removed from another site.

Techniques include:

- Non-cultured melanocyte-keratinocyte cell suspension transplantation

- Punch grafting (mini-grafting)

- Blister grafts, formed by suction or cryotherapy

- Split skin grafting

- Cultured autografts of melanocytes grown in tissue culture.

Depigmentation therapy

Depigmentation therapy, using 20% monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone (MBEH), may be considered in severely affected, dark-skinned individuals with vitiligo that has failed to re-pigment spontaneously or with therapy.

Cryotherapy and laser treatment (eg, 755-nm Q-switched alexandrite or 694 nm Q-switched ruby) have also been used successfully to depigment small areas of vitiligo.

Future therapies

Other novel potential therapies that are still under research include those targeting IFN-γ–JAK–STAT1 pathway (targeting CXCL9/10), anti-IL15 and anti-CD122 (targeting TRM), Wnt signalling antagonists, and others.

Psychosocial support

Vitiligo results in reduced quality of life and psychological difficulties in many patients, with problems like depression and poor self-esteem, especially in adolescents and in females. Patients should be assured that there is always something on the table to help in managing their condition, from using camouflage to available therapies with possible measurable improvement. The psychosocial impacts of vitiligo tend to be more severe in some countries, cultures, and religions than in others.

Family support, counselling, and cognitive behavioural treatment can be of benefit.

How do you prevent vitiligo?

Unfortunately, there are no proven effective measures to prevent vitiligo. Although dogma related to many theories, ayurvedics, vitamin supplements, and alternative medicine has been endorsed by many vitiligo support groups, these are not based on scientific evidence. Aggressive treatment may help in halting the progression of a rapidly progressive disease.

What is the outcome for vitiligo?

The clinical course of generalised vitiligo is highly unpredictable.

In general, vitiligo progresses slowly and gradually over months, then remains quiescent for years, and is usually difficult to control.

- Spontaneous repigmentation may occur after exposure to sun, mainly in younger individuals, but this is unpredictable and is usually incomplete. This usually starts as brown spots arising around the hair follicles (perifollicular), usually darker than the normal skin colour, where the overall size of the white patch may get smaller.

- Vitiligo can extend further, either by the appearance of new spots, or by peripheral enlargement of pre-existing ones.

- Cycles of pigment loss followed by periods of stability may continue indefinitely.

- Poor prognostic indicators include longstanding disease, leukotrichia, mucosal involvement, and Koebner phenomenon.

Bibliography

- Abdel-Malek ZA, Jordan C, Ho T, Upadhyay PR, Fleischer A, Hamzavi I. The enigma and challenges of vitiligo pathophysiology and treatment. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2020;33(6):778–87. Journal

- Bergqvist C, Ezzedine K. Vitiligo: A focus on pathogenesis and its therapeutic implications. J Dermatol. 2021;48(3):252-270. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15743. Journal

- Eleftheriadou V, Atkar R, Batchelor J, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of people with vitiligo 2021. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(1):18–29. Journal

- El-Domyati M, El-Din WH, Rezk AF, et al. Systemic CXCL10 is a predictive biomarker of vitiligo lesional skin infiltration, PUVA, NB-UVB and corticosteroid treatment response and outcome. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022;314(3):275–84. doi:10.1007/s00403-021-02228-9. Journal

- Picardo M, Dell'Anna ML, Ezzedine K, et al. Vitiligo. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15011. Published 2015 Jun 4. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2015.11. Journal

- Teulings HE, Overkamp M, Ceylan E, et al. Decreased risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with vitiligo: a survey among 1307 patients and their partners. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(1):162–71. Journal

- van Geel N, Passeron T, Wolkerstorfer A, Speeckaert R, Ezzedine K. Reliability and validity of the Vitiligo Signs of Activity Score (VSAS). Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(5):883–90. doi:10.1111/bjd.18950. Journal

- Weng YC, Ho HJ, Chang YL, Chang YT, Wu CY, Chen YJ. Reduced risk of skin cancer and internal malignancies in vitiligo patients: a retrospective population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):20195. Published 2021 Oct 12. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-99786-9. Journal

On DermNet

- Vitiligo images

- Vitiligo dermoscopy

- Vitiligo surgery

- Depigmentation therapy for vitiligo

- Hair and skin colour

- Pigmentation disorders

- Leukoderma

- Alezzandrini syndrome

- Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1

- Drug-induced vitiligo

- Skin signs of rheumatic disease

Other websites

- Global Vitiligo Foundation

- Vitiligo Association of Australia

- American Vitiligo Research Foundation

- The Vitiligo Society

- Camouflage for patients with vitiligo — Review article in Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology, January 2012

- National Vitiligo Foundation Inc.

- Vitiligo Support International

- Association Francaise de Vitiligo

- Schweizerische Psoriasis und Vitiligo Gesellschaft

- Vitiligo Society UK

- Vitiligo: Patient Handouts — The Society for Pediatric Dermatology

- Vitiligo — American Academy of Dermatology

- Vitiligo — British Association of Dermatologists

- Vitiligo International Patient Organizations Committee (VIPOC) - Searchable patient support groups